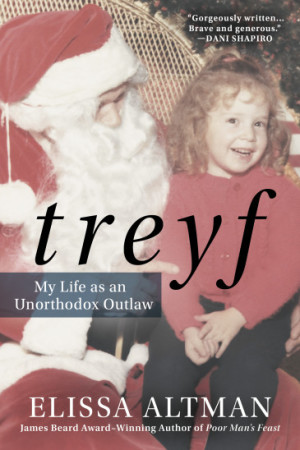

I’m excited to announce that my new memoir, Treyf: My Life as an Unorthodox Outlaw, will be released on September 20th, 2016, and is available for preorder. I’ve gotten scores of requests for a sneak peak from many of you. Please enjoy this small taste of Treyf:

From the Prologue

Fleishig or milchig?

It is 1995.

A middle-aged Hasidic antiques dealer on Second Avenue opens a splintering mahogany box and removes a tarnished silver serving set: a knife, a fork, a spoon.

We stand face-to-face in our respective uniforms: me, in paisley Doc Martens boots and a pilling, mauve Benetton sweater with broad, rounded shoulder pads that make me look a fullback. He, in sober black pants, black vest, black shoes, black suede yarmulke, and a white-on-white, chain-patterned shirt stained with the sweat of devotion, his tzitzit—the fringes of his prayer shawl—dangling beneath his fingers. A plume of graying black hair cascades up and out of his collar.

“It’s very nice,” he says, holding the fork up to the light streaming in through the windows, “but I see this pattern a lot. It’s from the Kennedys.”

After dating for five months, my parents married in 1962. My father was sure he had found the love of his life, and his future; my mother was sure she had found a way out of her parents’ house, and her future.

They were both right, and they were both wrong.

I was born nine months later, almost to the day. My father tells me this story for years, from the time I am old enough to understand what the words mean, and probably even before: that I was conceived on their wedding night, hours after their ceremony was presided over by Rabbi Charles Kahane—father of Jewish Defense League founder and crackpot firebrand Meir, murdered in 1990—and the kosher reception held at Terrace on the Park, overlooking the sinkhole that was Flushing Meadows, site of the World’s Fair two years later.

“It all happened very fast,” my father explains.

Before he married my mother, my father was engaged five times, each time to a woman his family deemed unacceptable.

“Treyf,” his mother said to me as she recounted the story, tipping her chin in the air and rolling her eyes: one was too big, another too short, another cross-eyed, another crazy, another not Jewish.

Treyf: According to Leviticus, “unkosher and prohibited,” like lobster, shrimp, pork, fish without scales, the mixing of meat and dairy. But also, according to my grandmother, imperfect, intolerable, offensive, undesirable, unclean, improper, filthy, broken, forbidden, illicit, rule-breaking.

A person can eat treyf; a person can be treyf.

“And then,” my grandmother said, “he met your mother.”

She folded her arms across her ample breast and heaved a long sigh.

My mother.

My tall, blond, fur model, television singer mother who I watched as men tripped over themselves to get to at the 1960s and 1970s Queens, New York, parties of my childhood.

When she met my father, a sack-suited, wing-tipped ad man specializing in postwar Long Island real estate, she had recently ended a relationship with the composer Bernie Wayne. Somewhere between Bernie and my father, there was someone I will call Thomas, a tall, Jewish, French-speaking, Sorbonne-educated beatnik who had purportedly once lived with Nina Simone, and whose diamond-dealer father had been knighted by the king of Belgium. When I was ten, my parents brought me along to one of Thomas’s legendary Saturday night Upper East Side cocktail parties, where I careened around the crowded apartment from table to table like a pinball, narrowly dodging the suede-patched elbows and lit Gitanes of the other guests. Invisible and unsupervised, I managed, just as the party was getting underway, to eat an entire block of pâté de campagne, a bowl of cornichons, and a round of stinking, oozing Époisses. An hour later, I writhed on Thomas’s bathroom floor like a snake and was comforted by some of the other guests while my parents went to get the car: the Hollywood Squares comedian David Brenner, who lived across the hall, rubbed my back; two hookers wearing matching black vinyl thigh-high platform boots and crushed purple velvet hot pants sang me a folk song with a cheap nylon-string guitar that one of them had brought along; and a long-haired man who claimed to be the drummer for Chicago scratched my head like I was a puppy. Forty years later, I can see the black-and-white octagonal tiles on Thomas’s bathroom floor, and I can feel the stiff nylon weave of the polyester shag rug burning my neck.

“Treyf,” my mother’s mother, Gaga, whispered to me as she mopped my forehead the next morning, while my parents slept soundly in their bedroom across the hall.

After their wedding ceremony, after the blessings were made by my paternal Grandpa Henry, a fire-and-brimstone Orthodox cantor, after the chopped liver was eaten, the gefilte loaf sliced, the Manischewitz Heavy Malaga poured and the hora danced, my parents drove to their honeymoon at the most modern of the upstate New York kosher borscht belt hotels, the Nevele, with their silver serving set locked in the trunk of their rental car. They had made it; they were finally legitimate. They had stepped on the glass, jumped the broom, leapt the chasm between freedom and conformity, adolescence and adulthood; they had done exactly what was expected of them.

Every member of my father’s family had the same set of silver—a Gorham service in the Etruscan Greek Key pattern—as if it was a shining periapt acknowledging their validity and confirming their eternal place in the clan. As a young child, I was regularly seated on a beige vinyl kitchen stool near the sink, while Gaga methodically polished the pieces; the process hypnotized me, and I watched without blinking how she tied a silk paisley kerchief around her nose and mouth like a bandit on Bonanza, poured the thick, pink Noxon onto a soft rag and massaged each utensil until it shone, silver and glowing and bright as a pearl. I was mesmerized by the pattern’s simplicity, and would hold the tarnished spoon on my lap and trace the design with my tiny index finger: it was nothing more than a straight line that flowed forward, then reticently coiled back on itself. It turned and moved forward again, repeating over and over without end. My father’s family didn’t arrive at Ellis Island from the old country with a family crest, and so we adopted the Greek Key as our own; it became ubiquitous, gracing everything from the edges of our linen tablecloths to our bath towels to the border around the hood of the English Balmoral pram my parents pushed me around the Upper East Side in when I was an infant.

A gift to my parents from my father’s sister and her husband and his sisters, the family silver bore witness to every tribal event that took place in our home from the early 1960s into the 1970s: tense Mother’s Day brunches and prim Thanksgivings. Funeral luncheons and birthday parties crackling with rage. It graced a decade of sweet Rosh Hashanah tables, prawn-filled cocktail parties, solemn shivas when well-meaning Catholic neighbors carried in trays of cheese-stuffed shells floating in meat sauce; holiday parties where bacon-wrapped water chestnuts and party franks were served with potato latkes; and Yom Kippur breakfasts where we set upon platters of sable and lox like a drowning man grabs for a life preserver.

When the parties were over, the only things remaining were invisible coils of gossip and the ancient family furies—the confidences breached, the grudges held, the forbidden flaunted and waved like a victory flag—that were spoken of in hushed tones and hung in the air like crepe paper streamers. Gaga waited until the last guest departed, plunked me down on the stool next to her, dumped the silver into the sink, and I watched in silence as she scoured away any trace of what had been eaten and what had been whispered, rendering it perfect and clean and kosher for the next occasion.

“So nu,” the Hasidic man says to me again, pushing his black plastic glasses up the bridge of his nose: “Do you know? Fleishig or milchig?”

Meat or dairy?

If I can assure him that the silver had been used in a devout home, where separate sets of plates and silverware are restricted for dairy and meat dishes, he won’t have to go to the trouble of koshering it for a Jewish customer wanting to buy it. He won’t have to put the set through the lengthy process of hag’alah—boiling the pieces while keeping them from touching each other so that every bit of the silver is exposed to the cleansing promise of the water, like baptism in a river.

I don’t know what to say, given all the years of meat lasagnas and pork dumplings and shrimp cocktails that the silver has served during my parents’ ill-fated marriage. After sixteen years, their relationship ended in the late 1970s, not in a modern Manhattan divorce court like in Kramer vs. Kramer, but in front of a beth din—a quorum of three Orthodox rabbis—who agreed, after some Talmudic debate, to grant them a get, a kosher document of marriage severance from husband to wife dating back to the days of Deuteronomy, and without which even the most assimilated Jewish couple, having gone through an American divorce court, is still considered married according to Talmudic law.

“Aha,” he gasps, holding up the knife, flecked with a tiny, hardened drop of dark red jam. He removes his glasses, holds his jeweler’s loop up to his eye, and confirms it with a combination of Talmudic reasoning and authority: “We don’t eat jam unless it’s with blintzes and blintzes are dairy. “Therefore,” he proclaims triumphantly, “milchig!”

The last time I saw my parents’ silver serving pieces in use was when I was ten, the night of my father’s fiftieth birthday in 1973 during an ice storm—the ice storm; the Rick Moody–Ang Lee ice storm when New York nearly came to a standstill—when the delivery boy from the local deli couldn’t get his truck up the street to drop off the trays of food that my mother had ordered for what was supposed to be a grand surprise party. It was a bust; there was nothing to eat. Grandpa Henry called just as we were all starting to hide behind my parents’ black silk couch, and I jumped up to answer the phone. My father walked in, exhausted, his Harris tweed overcoat caked with melting slush, his woolen driver’s cap wet and dripping, and everyone yelled “Surprise!” and my grandfather said that he wouldn’t be there because it was the Sabbath.

“Tell him for me I’m sorry, Elissala dahlink,” he said in his thick Yiddish accent, and then he hung up.

“He always goes to all your sister’s parties,” my mother snarled, “whether it’s Shabbos or not.” She pulled him into their bedroom where they fought behind closed doors while the hungry neighbors downed glasses of scotch and I raided the fridge and produced a beige melamine platter of overlapping sliced salami, intermarrying the Oscar Mayer with the Hebrew National like a Unitarian Venn diagram. I put it out with a jar of Gulden’s mustard and half a loaf of my mother’s crumbling Pepperidge Farm diet white bread that I judiciously sliced into points, the way I had once watched Julia Child do on television. With no sign of the deli boy, the neighbors left and returned with whatever they could exhume from their refrigerators and cupboards: Polly from across the hall made Jell-O salad with cubed lemon-flavored Brach’s marshmallow Easter bunnies unearthed from the bowels of her candy cabinet. Carole from two flights up defrosted a pound of chopped meat under a waterfall of steaming bathwater and made Swedish meatballs with a container of milk she procured from the vending machine in the basement. My mother’s best friend, Inga, came back with a small boneless ham that she had basted with glaze under high heat until it resembled an overgrown Halloween candy apple. By seven o’clock, I pressed my ear to my parents’ bedroom door, and the shouting had slowed—they were spent and exhausted—while my father’s boss was on his fifth Dewar’s and playing my little wooden bongo drums in the living room while freezing rain pelted our windows. Wearing a fez and with his shirt unbuttoned to his navel like Tom Jones, my father’s best friend, Buck, hacked at the ham’s candy coating with the tip of the silver knife while Harry Belafonte’s Zombie Jamboree played in the background. We all gathered around while my father sliced his birthday cake, which was decorated like the real estate advertising pages of the New York Times and had been sitting on our terrace in the December cold for the better part of a week.

Twenty-two years later, I stare out the window of the antique shop, watching the traffic barrel down Second Avenue. I can taste the gummy Swedish meatballs thick with curdled milk and the Easter bunny marshmallows in the Jell-O salad. I can smell Buck’s Paco Rabanne, and see him in his Glen plaid Sansabelt trousers, chipping away at Inga’s candy apple ham. The antique dealer will never know that the little speck on my parents’ wedding silver set is not jam, but a stray bit of petrified pork glaze, hardened when my parents were still married and Nixon was still in office.

My father liberated the silver set from my mother right before their divorce, before she had a chance to change the locks; he kept it for me for fourteen years, hidden away deep his mother’s walk-in closet in Coney Island, next to an ancient bottle of Slivovitz and a shopping bag stuffed with photos of long-dead cousins from the old country, taken right before the Nazis marched in.

“So you just took it?” I asked, when he guiltily came clean about it one Saturday when I was sixteen, during his parental weekend visitation. We were having dinner at the Praha Restaurant in Manhattan, and he was nursing his second Gibson and poking at a plate of warm, apricot-stuffed palascinta. It was a bitterly cold night; ice rimed the windows like a frozen beer mug.

“She’d hock it if I didn’t—” he said, his eyes red and pleading, “and then you’d never know who you are. I’m keeping it safe and sound until you get married; then, it’s yours.”

After I lied for years whenever my mother went on a tear about her missing silver serving pieces—“You know, don’t you?” she’d say to me; “You know that he stole them, you’re protecting him,” her brown eyes fierce with rage—my father handed it over to me unceremoniously when I turned thirty after I told him I preferred women to men.

“No use in waiting anymore, then,” he said wistfully, stroking the mahogany case. He turned and walked out, leaving me standing alone in the middle of my tiny studio apartment, cradling the purloined box in my arms like an infant. The premarital giving of the family silver set marked me both as an adult, the family’s most ardent rule-breaker, and the family’s certain failure; I would never marry a man, and the traditional handoff on my assumed wedding day—what I was taught as a child would be a big affair at a country club on Long Island with a tall white multitiered cake and my Aunt Sylvia dancing a Russian sher—would never happen.

“Who do you think you are, to cheat us out of joy, to break the chain?” Aunt Sylvia whispered to me quietly in her kitchen the Thanksgiving after I came out, when I helped carry in plates from her table.

“I don’t know,” I said

And I didn’t.

I had no idea who I was.

For almost two years, the silver pieces sat hidden and covered in a blanket of on the bottom shelf of my television armoire, tucked behind a stack of ancient VHS tapes. I opened it only on Yom Kippur, the Jewish Day of Atonement, when WQXR’s simulcast of the Kol Nidre services from Manhattan’s Temple Emanu-El began at sundown. The cantor chanted and I opened the box and released an angry Pandora: a musty, acrid pong rushed out of it like a wave and wrapped itself around me. The smell of the past—a gamey, transportive scent of despair and schmaltz and Aqua Net—made me woozy. I’d close the lid quickly and put the box back where I’d hidden it, complicit in my father’s pilfering, and where my mother would never find it.

The Greek Key signified our wandering path, our twisting course, our constant searching and moving forward while always turning back. It was a pattern of repetition; a tether to the past.

“Without it,” my father warned when he handed it over, “you’ll never know who you are.”

*

Advance Praise for Treyf: My Life as an Unorthodox Outlaw

“A brave and generous memoir, a lucid love letter to her own family’s history that…does the work of a great memoir in piercing the reader’s separateness, and reminding us that we are not alone. I love this book.”—Dani Shapiro, author of Devotion

“Treyf is a beautiful, brilliant memoir filled with striking images, unforgettable people, and vivid stories. Elissa Altman has given us the story of an era and a tribe, rooted in 1970s New York City, and wrought with such visceral love that the pages shimmer.”—Kate Christensen, Author of Blue Plate Special

“Treyf is a memoir that reads like a novel, a spellbinding portrait of a very specific world that also serves as a universal primer on identity, on loneliness, on the nature of familial bonds, on the ways we make sense of the mess of our lives. Gorgeous, singular, heartbreaking, haunting.”—Joanna Rakoff, author of My Salinger Year

“Savvy, warm hearted, and profoundly illuminating…The meaning of the forbidden—in a family, in a self—and the human needs we all struggle with are gloriously explored. This is a transforming book, one of the most satisfying memoirs I’ve ever read.”—Bonnie Friedman, author of Surrendering Oz: A Life in Essays

Available for Preorder

Amazon.com

IndieBound

Barnes & Noble