I’m only half-kidding when I tell people that producing a book — writing it, revising it, working with your editor, revising it again, getting reads from people you trust to look at your raw(ish) work, reviewing the copyedits, reviewing the typeset pages, releasing it once and for all to the publisher who sends it into production where it cooks over a period of several months during which you hear nothing and are driven mad by the silence until a box arrives and you rip it open and burst into tears and there is your book — is like doing Lamaze while running a marathon for (in my case) almost three years. Like birthing a baby, it is a labor of love. And although Samuel Johnson famously said “Nobody but a blockhead ever wrote for anything but money,” he was wrong: writers write because we are constitutionally incapable of doing anything but.

There are those of us who barrel from one book to another, without catching our breath. Some of us stop for a while, mid-stream, and come back to our work at a later date. Either way, it’s never easy: Masters of the form quake before the page, Dani Shapiro wrote in her seminal Still Writing, which, while I would not qualify myself as master of the form, made me feel marginally less insane on the days I spent staring at the computer screen, hyperventilating, trying to unravel the myth of an assimilated American Jewish family across three generations living in midcentury and deeply hungry — hungry for acceptance, hungry for illusory safety and security, hungry for love — until I got to the kernel of who they were in reality, who they were in myth, and who I am as a result.

Some years ago, I was ordered to stop writing, to put my pen down, to step away from the computer, to abandon my work.

It was a little crazy, and like watching a metaphysical spaghetti western being filmed on a backlot.

I can’t, I said.

Drop it, she said. Move away from the desk.

I can’t, I said. I held my hands up.

She drew first.

Her bullet caught me square in the chest, tore open my heart, and for a time, writing this particular story about being an alien felt, in itself, alien; early on, the words on my computer screen might have been cyrillic for all the sense they made to me. I had to heal my heart before I could come back to the work and to the act of unkinking the cord and clearing the line of static. I think that anyone who writes, whether they are overtly told not to or they just imagine angry gods hurling thunderbolts at them, faces this, at some point.

Ultimately, it is impossible for a writer to not do this thing that breathes air into her lungs, that she cannot escape. As I recently told Signature Reads, it was Junot Diaz who said that he writes because he can’t escape it, because it offers him a way to address and counter what it means to be human; this is why any writer writes.

This is why I write.

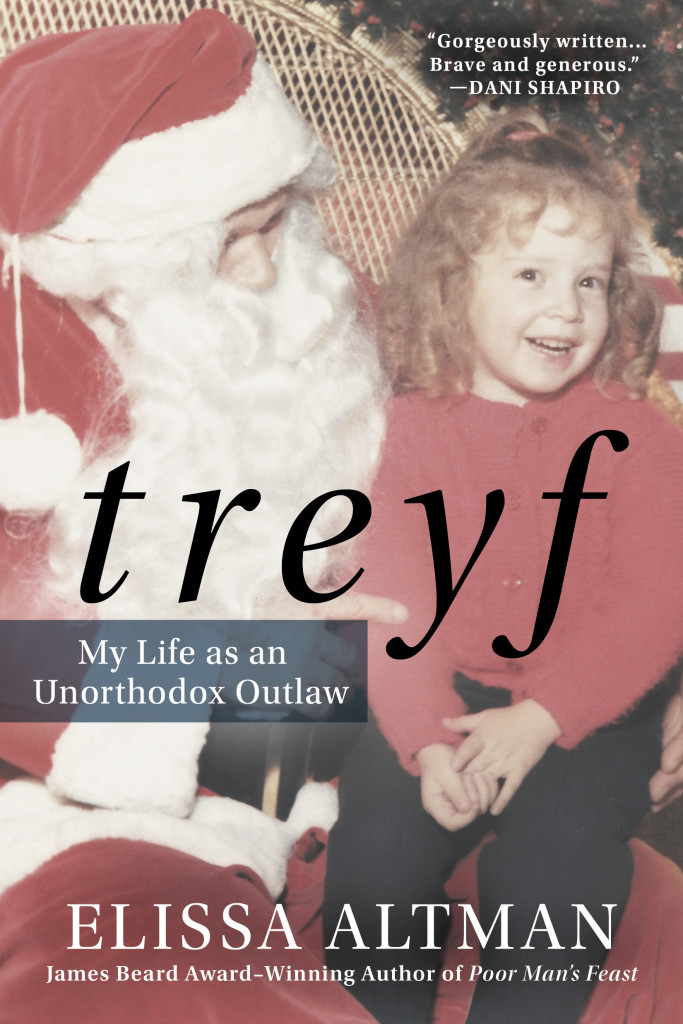

And this is why, at this particular point in my life — having published my first memoir three years ago — it was finally time to write about transgression, self-acceptance, and community, but also the issues of shame, overcoming hardship and pain, and, of course, love. Treyf is a story in which being an outsider longing for acceptance is a primary theme that plays itself out everywhere from religious practice to the dinner table to the bedroom. In writing it — in revisiting those times in which I overtly sought to always be a member of the winning team — I learned that it was the table and the act of nurturing that was the tie that bound us all together across the years, like a tether connecting divers in the muck, leading us to the light, bringing us home.