Last week, I drove to Boston for readings and signings at the great Wellesley Books and Brookline Booksmith, the latter of which was my local independent bookseller in the 1980s when I was a student at Boston University. Returning to Boston always feels like coming home, but it’s also bittersweet; it was the first place I lived alone, the first place I learned how to cook for myself (The simple: eggs, bowls of rice, steak, chicken soup. The tortured: pounded veal cutlets rolled around a filling of crispy pancetta and Fontina Val D’Aosta, and braised in dry Marsala fortified with a pound of butter. Vile.), the first place I discovered what being secretly, completely, hideously in love felt like.

This particular person cooked and so I did, too. That’s the way these things go.

At the time, it seemed incredible to me that someone my age could feed, nurture, and sustain herself and the people she cared about. Cooking, I thought, was an act reserved for older people — parents and grandparents — taking care of themselves and their families. People my age were why pizzerias and Cup-a-Noodle and sub shops were invented. I was sure of this.

Like most BU students, I crept my way further west down Commonwealth Avenue with each passing year, until I found myself no longer living in Boston, but in Allston, on the Brookline border. In the mid-1980s, it was a rough place to live; rumor had it that there were more cockroaches per square inch in Allston than people, and I once came home from my summer job as a Beacon Hill psychiatric practice assistant to my first apartment — an L-shaped studio directly upstairs from the area’s first Thai restaurant; every day, delicious clouds of lemongrass and curry wrapped themselves around me like a blanket — where I was greeted by a four inch-long water bug as exuberant as a puppy. My downstairs neighbor was a jet black-haired bass guitarist in a punk band that played every week at The Rathskeller in Kenmore Square ; he liked to position his amplifier on its back and crank the volume so loud that when he practiced, my shirts swayed back and forth in time where they hung in the closet. When I politely complained, he appeared at my door with a baseball bat, a row of safety pins piercing the entire width of his lower lip.

The 1980s.

Every weekend during the school year and the summer, my ritual went something like this: wake, coffee, eat breakfast (eggs or oatmeal if I was feeling virtuous; cold, leftover pizza from T. Anthony if I was hungover, which I often was), walk into Brookline to the Booksmith, past the beautiful, sprawling Victorian homes with their deep, tidy porches and ancient, massive elms. I’d dream — this is what you do when you’re in college — about the future, about the object of my affection, about safety and security and love, about growing up and growing old in a rambling, drafty old house in Brookline with a massive kitchen and creaking floor boards. I’d imagine myself living there, and by the time I reached the bookstore, I’d be lost in a reverie undone only with the purchase of a stack of remaindered paperbacks, and, at the neighboring health food restaurant, an iceberg lettuce salad tossed with a handful of cold canned garbanzo beans, and a small, damp sandwich made from something called Mock Chick’n Surprise.

But living there was not to be; by the time I graduated in 1985, I couldn’t wait to leave. Most of my closest friends — there were seven of us — had graduated a year earlier and were gone. I had been in love for the first time in my life — wildly, stupidly, mind-bogglingly so; unrequited and embarrassing, it surprised both me and the object of my forbidden passion: a deeply devout, very straight, Episcopalian woman from western New York State — and everywhere I turned were reminders of us. The day after graduation, I packed my father’s rented U-Haul in less than an hour; when I arrived at my mother’s apartment in Manhattan that evening, I realized what I’d left behind in my haste to get on with my life as an adult: my rusted-out Ross Eurosport bicycle, a box of photographs of my college friends, a Vietnam-era Army jacket I’d found in a used clothing store at the start of my freshman year, the name patch — Corporal Tedesco — beginning to fray with time. The only thing I took: my guitar, my clothes, my books, and the white and blue-flowered Correlle-wear service for twelve that my father bought for me when I moved into that first apartment: if I was actually going to cook, he said, I was damn well going to cook for someone other than myself.

I didn’t return to Boston for a long time; it was too hard. When I finally did, I imagined that I saw her everywhere, in quick glimpses out of the corner of my eye, down alleys and side streets where we used to walk after class, on leafy St. Paul Street in Brookline, at the vegetarian restaurant on Harvard Avenue, outside the Victorian house with the rambling, open kitchen where I was certain we’d live someday. The thought of her left me undone, and when I ran into her ten years later at the funeral of a mutual friend, she talked to me as though nothing had happened; the weight of our story had been carried only by me.

Did you ever learn how to cook, she asked.

I went to cooking school, I said.

She hugged me and smiled, and floated away like a ghost.

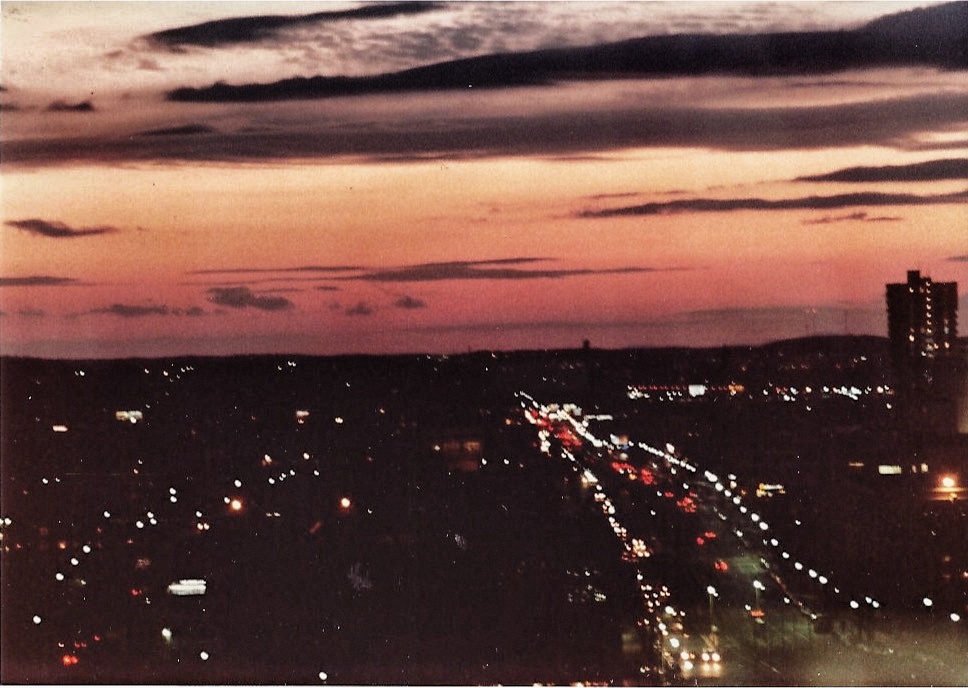

When I arrived in Boston last week, the day after my Wellesley reading, I did what I always do when I first get there: I parked the car a little bit west of the building that was my freshman dorm — Warren Towers — and looked up at what had been my 18th floor window from 1981-1982. For one solid year, not yet out of my teens, I stood there and watched the sun set every night; I looked west into Brookline and imagined what my life would be like after graduation, where I would live, what I would become, who I would cook for, who I would love, and who would love me back.

Last week I stood on Commonwealth Avenue before my reading, gazed back at that eighteen year old girl and told her: she would find joy in the act of nurturing and sustaining others, and she would marry the love of her life, who actually loved her back. And that things would be good.

I wished her well, and drove to my reading.