I couldn’t peel it; my hands shook.

I ran them under cool water and dried them on my favorite blue striped linen towel hanging off the oven door handle — the one that I never use, that I’m afraid to stain lest it cease being the new, fresh, perfect towel that it is. Still, my hands trembled, and when I tried to peel the morning’s freshly boiled egg, I failed. I brushed the shell away with my thumbs to coax it off like my grandmother used to do when she made eggs for me in the chipped black and white enamel saucepan of my childhood. Instead, I gouged it violently, my thumb piercing straight through membrane, glair, crumbling orange yolk with its halo of overcooked green, until all that was left of the egg was the suggestion of sustenance.

My throat tightened. I fought back tears, and laughed at the utter ridiculousness of it: to cry over a mangled egg is inane and emotionally frivolous. Boiling an egg on this particular morning during this particular winter was all I could possibly manage, and I couldn’t even manage that.

We call one another good eggs, tough or rotten eggs….We walk on eggs to spare fragile egos….We find the bestowal of an egg to be expressive of wildly divergent emotions: handed over graciously it betokens favor; delivered at high velocity it plainly indicates disgust, said Robert Farrar Capon. I add to this the egg’s subtext of Life, cap L, and hope: in The English Patient, when David Caravaggio, erstwhile spy and thumbless thief, produces a single, purloined fresh egg for Hana, it means that the war is nearly over. When he drops it and it splatters at his feet, we know that the war will continue, however briefly, and more will die.

I grew up having an egg every morning of my life. My father and I sat side-by-side at our Danish modern kitchen counter in Forest Hills, our backs to the Chambers stove where my mother silently soft-boiled two of them for three minutes, cracked them over slices of cold diet white bread stuffed like cotton balls into two brown melamine egg cups, and set them down in front of us. Years later, in the egg white omelety 1980s, I began to curtail my egg intake because of the genetically high cholesterol I was gifted from my mother. In the 90s, I discovered oeufs en meurette at the defunct La Goulue in Manhattan, and would have them once a year when I took my mother to her favorite restaurant for Mother’s Day. In the early 2000s, I married Susan, who taught me how to make a meal out of a perfectly poached egg on garlic-rubbed sourdough toast drizzled with olive oil; we ate this at least once or twice a month. In the mid-early-2000s, when I began to write full time from home and was blessed with a chicken-keeping neighbor, I started making a single boiled egg every morning: I would sprinkle it with sea salt, roll it around in a shallow stoneware dish of dukkah, and eat it standing up in the kitchen, the dog at my feet. And then, like clockwork, my mother would call.

I can’t talk, I’d say. I’m having breakfast. I’ll call you back.

What are you having? she’d ask.

An egg, I’d say, my mouth full.

I’ll stay on the phone with you while you eat, she’d say. I’ll do the talking.

And she did: sometimes happy, sometimes angry, often raging against one person or another who had somehow done her wrong. There were laundry people who used the wrong detergent, cab drivers who took her the wrong way to her destination, makeup that she’d ordered that didn’t arrive when she needed it, an accompanist who didn’t return her call, the Jewish deli that forgot to remove the peas from her matzo ball soup. There were old friends of sixty years with whom she was engaged in constant battles, bus drivers who drove too slowly, bus drivers who drove too quickly, the cable company who was trying to bilk her, her long-deceased ex-husband — my father — who she was convinced was crazy, her second husband who didn’t make provisions for her before he died of a cerebral hemorrhage, and Perry Mason, who she was completely in love with even though 1) he didn’t actually exist in real life; 2) Raymond Burr was dead; and 3) when he wasn’t dead, he was gay.

It wouldn’t matter to me, she’d add, and continue on.

I have to go, I’d say, wiping the dukkah crumbs from my mouth.

After her fall in December — after the surgery and the rehab and the return to her home with a caregiver — her morning calls came earlier. A pre-dawn text from the caregiver would come in first: She’s calling you in five, she’d write. Just FYI.

By January, cartons of eggs — my neighbor’s chicken eggs, a plastic tray of quail eggs, six duck eggs that I’d bought over the holidays as a treat — began to pile up in the refrigerator, shoved into the back alongside half-empty jars of Hellman’s mayonnaise and squashed tubes of anchovy paste; I lost track of them, and couldn’t remember which ones were old and which were fresh. I forgot to eat breakfast, and sometimes lunch. I’d look up from my computer at three o’clock, the sky outside my office beginning to change, and realize: I hadn’t eaten anything all day. My skinny jeans began to hang off me.

You look terrific, my mother would say, when I’d come to visit every week. You have cheekbones again.

How are you sustaining yourself, a friend asked me. What’s the easiest way for you?

Eggs, I told her. But I have no appetite.

Don’t you understand, she said. Eggs are life. They are perfect. Boil one for yourself. Every morning. Even if you don’t eat anything else until dinner, you’ll be okay.

The next day, after Susan left for work and the dog had been walked, I took out the carton containing the ones from my neighbor; they were large, small, narrow (one of her girls lays eggs that are nearly flat), round. They were blue, green, and white. There were brown speckles on some, and bits of feather stuck to others.

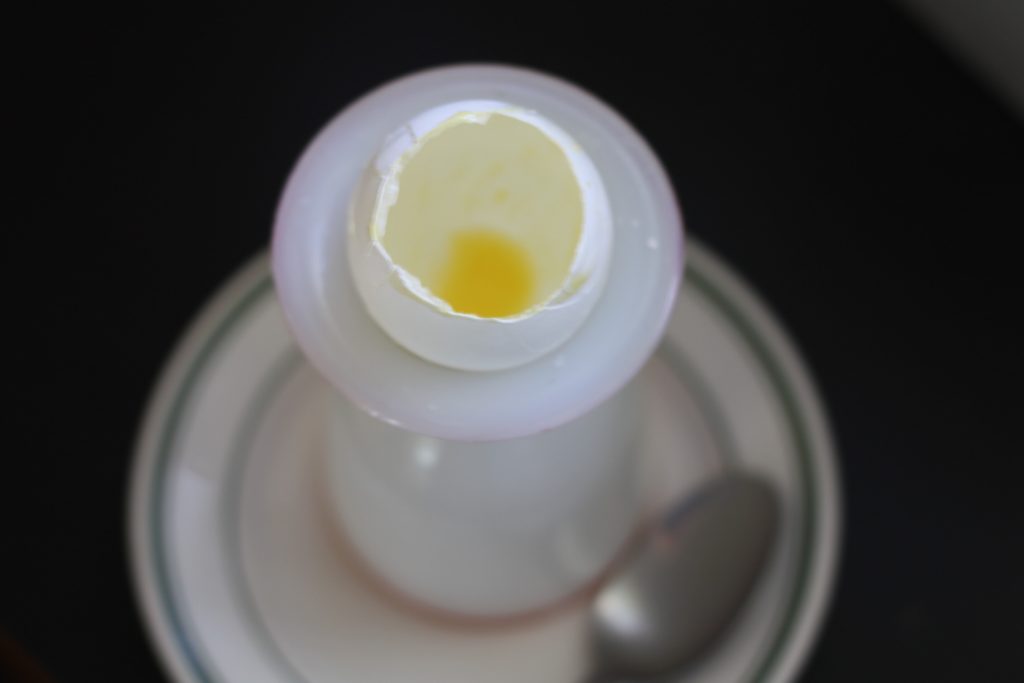

I placed a small green one in my favorite ancient Le Creuset butter warmer. I filled it with water, put it on the stove, and when it boiled I covered it, removed it from the heat, and set the timer for twelve minutes. When the bell went off, I drained the pot, ran the egg under cool water until I could handle it, stood over the sink, and tried to gently peel it. The phone rang four times and stopped.

I peeled.

The phone rang again and stopped.

I peeled.

The phone rang again, and I plunged my thumb through the shell; it came out the other side. I cried at the absurdity of it: I was a food writer who couldn’t even feed myself an egg, or provide myself with the most basic form of life-giving sustenance. The egg is arguably the world’s most perfect food and I had destroyed mine. I dropped its remains into the butter warmer, and put the pan in the sink. I looked out the window at my backyard, partially covered with snow.

The cold New England winter sun streamed into the kitchen; it was a quiet time of day.

The phone rang again; I let it go.

I picked up what was left of the egg, and did the best I could with it; it was misshapen in places, broken, flecked with shards of shell. I dropped it back into the tiny pan, sprinkled it with sea salt and dukkah and ate every last drop with my fingers, savoring its promise of sustenance, its imperfection, its symbol of the maternal.