Sometimes, life careens off the rails.

Recipes don’t work. Unexpected bills show up. Jobs fail to materialize. Deadlines mysteriously disappear from your calendar. Colleagues betray you. People you love get sick. Relationships hit speed bumps.

Sometimes, these things even happen all at once, and you find yourself hiding under a large piece of furniture in a fetal position, eating a pint of pistachio gelato and humming along to Das Rheingold.

The last few weeks have been like that over here, and I haven’t much liked it. There’s been a lot to do lately: finish writing the book and send it off to my editor, plan my mother’s birthday celebration, attend my cousin’s 40th wedding anniversary party in Washington D.C., attend a wedding in Manhattan on the same weekend, finish editing a cookbook, plan the meals that Susan will be able to eat after her surgery next week, which we hope will cure her apnea and the snoring that has rattled loose the shingles off the sides of the house lo these eight years that we’ve lived here. We’re also talking seriously about returning to New York, and trying to come up with a reasonable game plan despite a hideous real estate environment and the fact that not many people like to give mortgages to freelance writers; while I’d like to blame them, I can’t.

The bottom line is that everything is involving a lot of planning and doing and thinking, and it’s always during moments like this when Life seems to jump up and bite you in the ass like an angry pit bull so that you spin around on your heels and pay attention to it.

What the hell do you want? you ask it, like someone jabbed you with an andiron.

I will not be ignored, it answers, like Glenn Close in Fatal Attraction.

And really, it won’t.

A few weekends ago, I picked Susan up from work in Manhattan and we drove down to the Main Line, outside of Philadelphia, to stay overnight with a good friend we’ve seen precious little of over the last few years. We were shocked to find out that one day not long ago, her husband had gone off on a road trip to visit his adult children, and decided to have a midlife crisis and not come home. Just like that. Our friend, given to constitutional stoicism, is in as good a shape as one could possibly be given the circumstances.

When Susan and I arrived down in Pennsylvania that night, our friend was out, and so we decided to have dinner at a local Thai restaurant which was supposed to be very good. It was, but we also noticed that as we sat there, loudly smacking our gums over the delicious, peanutty steamed Thai crepes that were brought to our table — made from glutinous rice flour and with a jiggling texture that can only be accurately described as squidgy — none of our fellow diners were talking to each other. Couples — obviously long-married — were scattered around the restaurant, and apart from the older lady sitting next to me who, out of a dead silence, proclaimed to her embalmed-looking husband that Gilbert & Sullivan’s H.M. S. Pinafore was playing in a neighboring town and she for one was intending on going with or without him, it was about as frigid in that place as a mausoleum.

So we gobbled our dinner much to the delight of the owners, who clearly had never witnessed such gustatory enthusiasm in their midst; we then fled for our lives and our love, back to our friend’s house which, apart from his shoes still sitting in the entry way, bears little evidence of her soon-to-be-ex husband. It’s all very weird, and sad, and all I could think of the entire time we were there was I really want to bake this woman an apple cake.

Very late that night, I was in the process of setting the alarm on my iPhone when I received an email from an old friend I’ve known since we were children in sleepaway camp, and with whom I had fallen out of touch after leaving New York eleven years ago: her husband had died, she said, and she thought I’d want to know about calling hours. I gasped as though someone had kicked me in the stomach: she had been alone for a long time and finally met her man after some very serious searching. In short order, they were married, and had a beautiful little girl, and they were happy. And now, just like that, he was gone.

I looked over at Susan, who was drifting off to sleep, and I laid awake the rest of the night, staring at the ceiling.

We drove the rest of the way down to Washington in the morning, and that night found ourselves sitting at a long, long table in a private restaurant dining room surrounded by throngs of family and friends and children who gathered to celebrate my cousin Nina and Robert’s 40th anniversary. We had gone over to their house in Virginia a bit before dinner, and brought with us three stellar bottles of Prosecco, a gigantic wedge of Humboldt Fog, and an even bigger wedge of Stilton, and we all stood around the kitchen table, drinking and eating enormous quantities of cheese, which we all love. I’m always drawn to the kitchen in Nina and Bob’s house because, while I’m drawn to the kitchen in every house I walk into, theirs contains the wrought iron chairs that sat around my childhood dining room table in Forest Hills. I can’t help but look at them and think of the (many) times my father caught his belt loop on one of the curly-cues that make up the back of the chairs, and accidentally dragged it through the kitchen on his way to the bathroom.

At Nina and Bob’s, there was much laughter; these people, in the face of travail and trial, love to laugh, and they will find any reason to do it. And when we’re with them, so do we, which is a good thing when life jumps up and bites you in the behind.

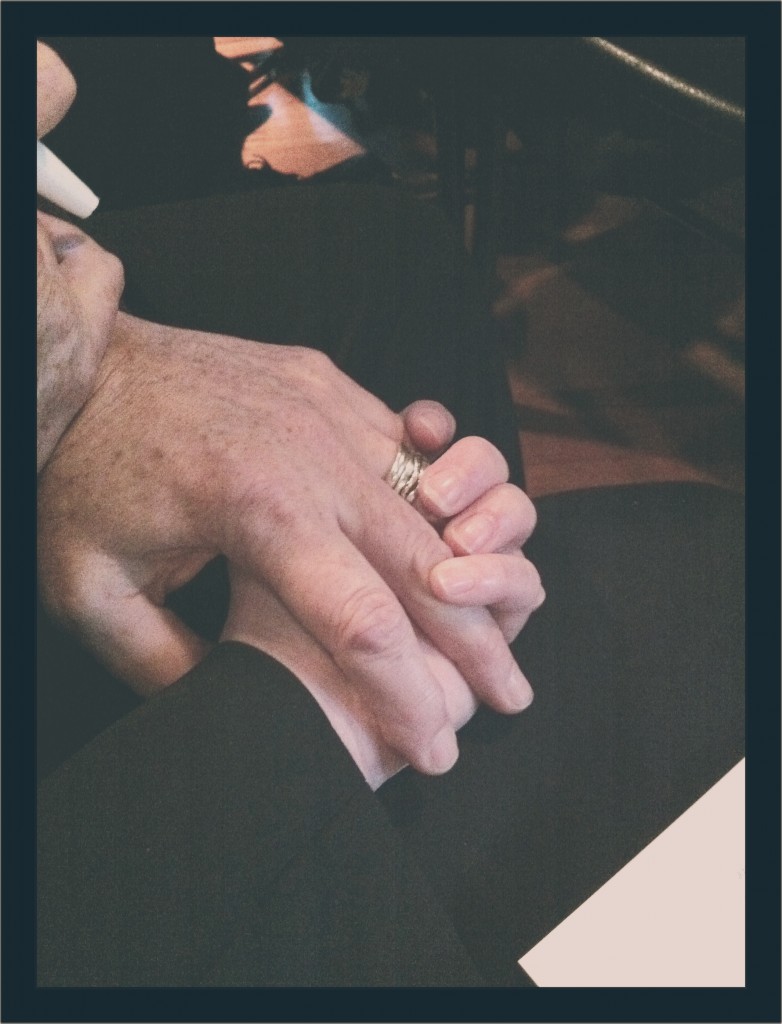

We left early the following morning and headed back up to New York, stopping to pay the condolence call to my old friend whose husband had died; the place was heavy with grief, and there were piles of cookies and cakes and fanciful, flower-like arrangements of fruit — who invented that? it’s a bad idea — sitting on the entry way table in the immense Upper West Side apartment that belonged to her mother-in-law, who appeared to be suffering from dementia so hideous that she didn’t even know that her son had died. No one was eating — the cakes and cookies and fruit were nothing more than decorations and offerings of peace from socially stunned visitors; I sat down on the couch next to my friend and reached over and held her hand for a minute — it had been years since we last saw each other.

“This is life,” she said, looking surprised. “Right?”

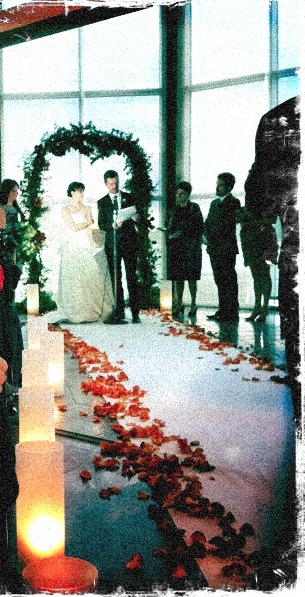

A few hours later, we attended my friend Diane’s daughter’s wedding, ironically in the same place my cousins Mishka and Bill were married a few years back. We stood around before the ceremony and went outside to look at the Hudson as the sun was starting to set.

What a sandwich, Susan said, whispering to me and shaking her head, as we looked around at everyone dressed up in wedding finery.

A sandwich?

“Divorce on one side, a 40th anniversary party and a condolence call in the middle, a wedding on the other side. It’s all there: marriage failure, marriage success, marriage end, new marriage. Life.”

That night, we watched two (very young) people get married, surrounded by masses of friends and well-wishers and music and food, in one of the most spectacular weddings I have ever attended. And I’ve attended lots. His dad, a well-known, critically-acclaimed Nashville songwriter, sang to them. Her dad, a not-so-well-known, critically-acclaimed consultant, presented them with a Quaker wedding certificate. Her mom, a well-known food writer, gave them a recipe for a happy life, which included the instructions to Keep It Hot. We love Mom.

I tried, unsuccessfully, not to whimper through the whole thing. We danced exuberantly, which we haven’t done in a long time; it was wonderful — possibly the most wonderful wedding I have ever attended. It was even wonderful when Susan, while dancing, two-stepped across the bride’s long and gorgeous Vera Wang train that probably cost as much as a studio apartment, and fell on her ass, pulling me down with her. We laughed, to the dismay of some members of the wedding party, who doubtless thought we were inebriated, which we were not.

We were just celebrating life.

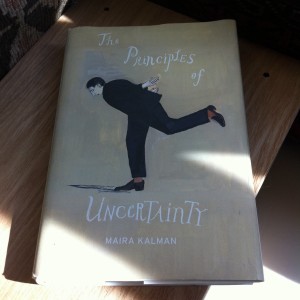

Jewish Apple Cake

There’s something about an apple cake that wraps itself around you like a blanket; I’m not sure what it is, beyond the fact that nearly every Jewish grandmother I have ever known makes a version of it, and, generally speaking, Jewish grandmothers can be very comforting (unless they’re torturing you). Serve yourself a nice slice of this cake, the recipe for which was hand-written on an index card stuffed into a 1947 Jewish community cookbook, with a glass of tea. You’ll thank me. (Really.)

Serves 8

1 cup unsalted butter

2 cups granulated sugar

3 large eggs

3 cups flour, sifted

1-1/2 teaspoons baking soda

1/2 teaspoon salt

1 teaspoon cinnamon

1/4 teaspoon nutmeg

1/8 teaspoon allspice

3 cups peeled, cored, and roughly chopped tart apples

2 cups chopped walnut meats

1 teaspoon vanilla

Preheat oven to 325 degrees F. Grease and flour a 10-inch bundt pan.

In the bowl of a standing mixer, cream together the butter and sugar until ribbony and light lemon yellow, about 2 minutes. Break the eggs into the mixture one by one, beating them into the batter until just incorporated.

Sprinkle in the sifted flour, baking soda, salt, cinnamon, nutmeg, and allspice, and fold together so that the mixture is thoroughly blended. Add the apples, nuts, and vanilla to the batter, and combine well.

Pour the batter — it will be very thick — into the prepared pan and bake for 1-1/2 hours, or until a tester inserted into the middle of the cake comes out clean. Turn out onto a wire rack and let cool before slicing and serving.