Over the last ten or so years, I have sat on countless conference and symposium panels, dressed in different hats. Sometimes, I wear my prim editor’s hat — not quite a pillbox, it sits painfully safety-pinned to my head lest it be blown away in an electronic windstorm. Sometimes, I wear my writer’s hat — a vintage one, its gray hatband missing from years of benign neglect, it’s now pulled on so firmly that it’s hard to remove. Other times, I wear my baseball cap backwards so that the peak doesn’t cast a shadow on the speech that I’ve downloaded to the iPad that generally, when I am not reading it on train trips or long commutes, lives in my kitchen, right next to my stainless steel fridge.

Over the last ten or so years, I have sat on countless conference and symposium panels, dressed in different hats. Sometimes, I wear my prim editor’s hat — not quite a pillbox, it sits painfully safety-pinned to my head lest it be blown away in an electronic windstorm. Sometimes, I wear my writer’s hat — a vintage one, its gray hatband missing from years of benign neglect, it’s now pulled on so firmly that it’s hard to remove. Other times, I wear my baseball cap backwards so that the peak doesn’t cast a shadow on the speech that I’ve downloaded to the iPad that generally, when I am not reading it on train trips or long commutes, lives in my kitchen, right next to my stainless steel fridge.

Whatever hat I wear, there is always the inevitable question that comes up, either as the subject of the panel I’m on, or directly from an attendee:

So when, exactly, do you think the digital world will kill cookbooks?

My answer is always the same:

Never.

Sometimes, there’s guffawing. Sometimes, I hear strains of relief. Sometimes, people get up and shuffle out. But the fact is, there is nothing to worry about: cookbooks, contrary to Julia Moskin’s wonderfully-written New York Times piece about apps potentially rendering cookbooks obsolete, are not going anywhere. In fact, in the face of the more remarkable apps out there, like Dorie Greenspan‘s amazing Baking with Dorie, cookbooks will be better produced, more interesting, and more desirable for one reason: they’ll have to be.

As a longtime editor (I went straight to work for Random House after graduation from college in 1985, then took a break to attend cooking school and to work at Dean & Deluca as a specialty cookbook buyer; then went to Little, Brown and then to Harper for ten years; there were a few other editorial pitstops along the way) who came of age at a time when “food media” toggled back and forth between books and their television tie-ins, I saw cookbooks increasingly become products timed to release simultaneously with their on-screen counterparts. Bookstore shelves were packed with this “product” to the degree that the average shelf lifespan for the average “B” list book (in other words, a book produced by a midlist author who has not yet become a household name or a bestseller) was six weeks; the rule of thumb among chain stores was that if a “book product” didn’t “move” within that time period, it wasn’t going to, and it was sent back to the publisher as a return.

Qualitatively-speaking, the faster these “book products” were being cranked out to appear with their television tie-ins, the more flimsy and slipshod they became: paper quality suffered. Recipes weren’t tested. Edits were truncated. Photos were mistakenly repeated pages apart. Proofreads lost importance. Cookbooks suddenly became the equivalent of the inflatable Paul McCartney that my father bought for me in the mid 1960s, when The Beatles’ Saturday morning cartoon series eclipsed everything else in the same time slot: when inflatable Paul, who was made cheaply in China, sprung a leak, we just patched him up with duct tape, until his head was completely swaddled in it and he began to resemble Marley’s ghost. Inflatable Paul was never meant for the long haul or for snuggling with, in the same way that a lot of the cookbook “products” I speak of above weren’t meant for long haul cooking and certainly not snuggling: their spines would break and their pages fall out, but in the end it didn’t really matter, because it was really all about the television show. Cookbooks, in many cases, were thought of as a secondary “support” to a primary “new media” product, that being television, and a few years later, video.

Eventually, even as cookbook quality slipped, publishers began to fuss and fret about how the books were going to be used, or even if, in the face of this new media; I remember the day I sat in an editorial meeting, and my publisher announced that “if home cooks can watch Jacques Pepin boning a chicken over and over on a video, they’re not going to buy a book to read about it.”

Years before I sat in that meeting, I was instructed by Joel Dean to carry the paperback edition of Pepin’s instructional opus, La Technique, in my department at Dean & Deluca. It was — it is — a remarkable book featuring black and white, step-by-step images for doing everything from correctly making choux pastry to filleting a flatfish. It takes time and patience and unerring focus to work from it; it assumes a certain level of concentration and dedication to task, as do all serious instructional books. When Julia Child described in both words and illustrations how to bake a baguette in 36 pages, she did not assume that her reader suffered from the media-related attention deficit disorder that now plagues us all; the affliction that thrives on, prizes and applauds the reduction of a human thought to 140 characters had no place in her work, as it doesn’t for anyone who wants to put method to steadfast practice. Julia, love her or hate her, assumed that her readers wanted to learn, and to learn thoroughly. Other instructional bibles followed, from Jacque’s to Anne Willan’s and James Peterson’s and, more narratively, Richard Olney’s, who instructed in words only how to turn a chicken inside out like a pillowcase for his poulet farci duxelles.

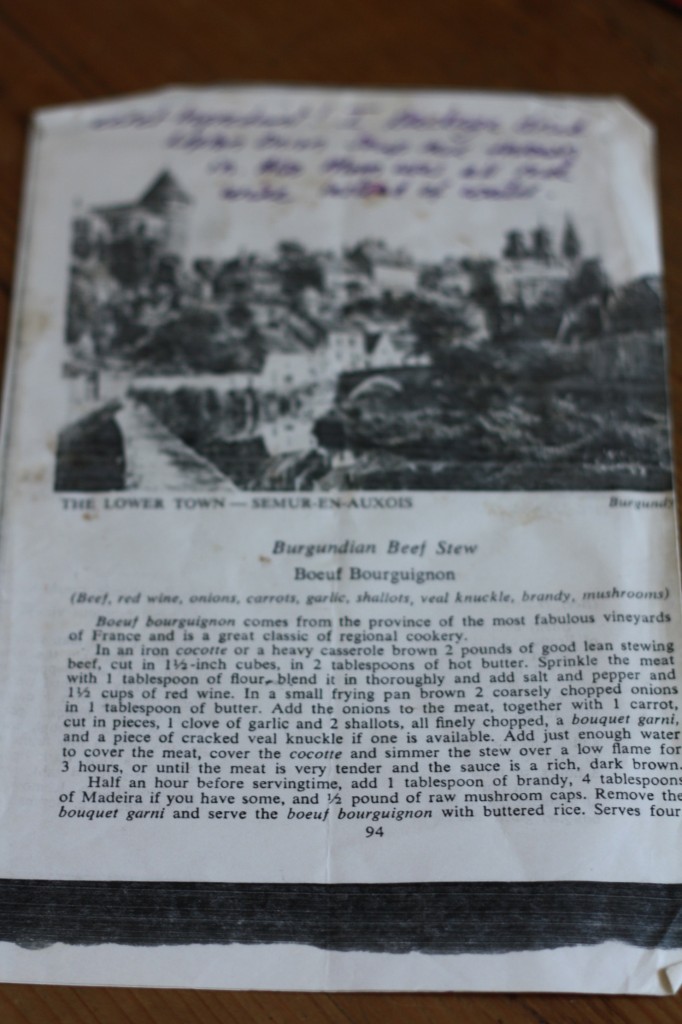

Beyond instructional content, cookbooks — good cookbooks; not the secondary product I mention above — are often read like straight narratives. Years ago, Paula Wolfert’s Mediterranean Cooking sat on my nightstand, and before I cooked from it, I read it like a memoir; when I was finished, I was drawn to the work of Lawrence Durrell and Paul Bowles (and if you’ve read Paula Wolfert’s work, you know why) and Elizabeth David. I cooked from the book too, and years later I still make the pasta con mollica di pane and bisbas michchi found within those pages; the book is alive with sights and smells and texture and poetry, and reading it, my brain wanders down alleyways it would never travel via a digital medium. When I made Wolfert’s paella, I accidentally splashed olive oil onto the recipe page; when I open the book today, I swear I can still smell it — I certainly can see it on the stained page, and I recall the dinner party I had the night that I made it, right down to the wine I served (Taurasi Salice Salentino 1995). Cooking and reading actual cookbooks show me where I’ve been; they reek of history, and anchor me in the way that, however vague, the assembly directions for Thanksgiving turkey in the 1951 Joy of Cooking anchored my aunt when it was just her and the book, and the concept of the iPad app was about as Jetsons as power steering.

Publishing is a sometimes fearful, ancient business that has, for the last ten years, been chewing on its collective fingers over what I call monomedia, or the belief that readers will get their information one way and one way only, exclusively, and not from books because they’re not sexy enough to compete with digitalia. To be clear, there is no question that cooking apps have claimed a seat at the publishing table, and rightly so: the ability to watch and re-watch Dorie Greenspan feel and poke biscuit dough so that you can actually see its correct consistency is unmistakably brilliant, and enormously valuable. I own the app, and use it, and will likely give it as a gift to many friends this season.

But to claim that the advent of the cooking app is going to render cookbooks obsolete is misguided; the digital must complement print, and vice versa, in order to achieve the innate balance between what Sven Birkerts calls, on one side, “the reading encounter, the private resource …” and on the other, “the culture at large, and the highly seductive glitter of mass-produced entertainment.” The response to the need for this reading encounter — this private resource — has been coming largely and most creatively from smaller cookbook publishers and highly-skilled self-publishers both in the United States and Britain who have eschewed the glitz and the six week bookstore sell-in, and instead purposely produced the kind of high production value cookbooks that are meant to be read, cooked from, cherished, and savored again and again. And they’re not going away any time soon.

Where Julia Moskin got it wrong is in describing the notion of “recipes that exist only as a string of words” as a relic. Recipes — the writing of them, the printing of them — show us who we are; they speak of what Birkerts called in The Gutenberg Elegies,” the immobilization and preservation of language. To make a mark on a page is to gesture towards permanence.”

Cookbooks are about a sort of gastronomical cultural stability, and historical durability; they tell us who we are, as humans. Digitalia, in all its glitzy, glittering ability to visually elucidate, is at best, fleeting and illusory. And at every conference and symposium at which I’ve spoken, someone invariably stands up and announces in one breath that PRINT IS DEAD, and a few hours later, while sidling up to the bar for a glass of artisanal, small-batch bourbon, haughtily proclaims that his agent has just sold his next book.

“I grabbed the brass ring,” he says, “….again!”