She has never slept, for as long as I can remember.

First, there was the hair, which, when I was very small, was very tall; these were the days of teasing, and to keep her updo in place, she climbed into bed every night next to my father with three feet of toilet paper wrapped around her head, a six inch tail of Charmin hanging off the pillow, blowing in the air-conditioned breeze like a Coppertone banner dragged behind a beach plane. She lay there stiffly all night, immobile and exhausted, and sat up the next morning, her hair perfect.

Eventually, it was just plain pique that kept her awake — the constant working of herself into a lather over imaginary transgressions, while my father and I and the world around her, ever the transgressors, slept soundly. When the black and white numbers on her bedside clock flipped over to 6:30 a.m. and the alarm went off, she swung her legs off the side of the bed and stood up, already furious and seething.

And then she made eggs.

A lot of eggs.

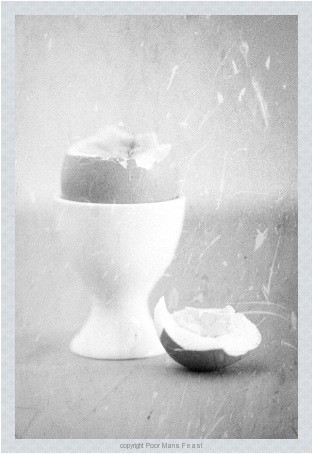

At first, when things were still good and happy, they were soft boiled, and sat in the broad end of our porcelain egg cups, their tips sliced away so that my father and I — perched side by side at the breakfast counter half an hour before he dropped me off at the school bus stop on his way to the subway — could dunk untoasted fingers of Pepperidge Farm Diet White into the runny yolk. As my parents’ marriage wore on and she grew angrier, the eggs were medium boiled, their firm yolks like thick golden velvet, with spots of remaining tenderness just barely discernible.

When I turned fourteen, my mother began hard boiling our eggs; she’d put them in a small pot filled with a shallow inch or two of water, set them on the stove, crank up the flame, and walk away. Eventually, they’d explode, their snow white glair erupting like Vesuvius through the fissures of her discontent. I’d refuse to eat them at that point, and when she came back into the kitchen, she’d grab the black plastic handle of the pot and dump its contents — the water had long since evaporated — directly into the trash.

My parents divorced the following year.

My mother still doesn’t sleep, and she still cooks eggs every single morning, even with cholesterol that hovers near the 400s if she’s forgotten to take her Lipitor. She’s been through a passel of saucepans — the brown and white Dansk pan that followed her into the city after her divorce, and that she burned until its white enameled interior melted away into a noxious cloud; two RevereWare pans that we brought to her apartment from our basement stash— they’d belonged to Susan’s mother who had them for fifty years. My mother burned them until their insides turned black as coal. Now she uses a tiny butter warmer, big enough to hold exactly one jumbo egg.

Eggs are my mother’s mood barometer: when she’s happy, she’ll deftly separate yolk from albumen, throw out the former, dump the whites into the one tiny stick-proof pan she owns, and while they bubble and spread, she’ll lay a piece of Diet White bread right down in the middle of it, and top it off with a dollop of honey. This, she says, is her version of French toast, and she loves it. If Susan and I are staying there and she’s feeling glad, she’ll insist on scrambling some whites for us because, she says, they’re low fat and good diet food, and together we’ll sit at her dining room table, having breakfast, while the traffic rumbles down West End Avenue twenty-one stories below. Not overcooked and not runny, the eggs bear no evidence of seasoning; it’s just them and us, a piece of bread, and my mother’s favorite morning cup of hot water. If we’re staying there and she’s furious, she’ll boil the eggs until a sulfuric haze wafts out into the living room; we’ll leave while the pan is still rattling over the flame.

“I had to throw them OUT,” she’ll tell me later.

The correlation between cooking and scorn is a fraught, famous one; food created by angry people seems, somehow, to be bitter, and so attuned to their off flavors and textures am I because of my mother’s eggs that once, when a conversation with a well-known cookbook author took a sudden and surprising turn south, I had to get rid of her book, because every one of the dishes I cooked from it after our argument tasted of her rage; no matter what I did, none of the recipes worked anymore. Food cooked in anger becomes collateral damage; meat is carbonized, pasta becomes starchy mush, vegetables go limp and sad, and it’s not like you can — or even want to — revive them, to coddle or comfort them, or to save them for another meal. You simply can’t do it. If the optimum way to cook and live and run a kitchen is, as Tamar Adler says, with economy and grace — use everything, every shard and peeling and drop of fat with care, kindness, and thoughtfulness — scornful cooking results in the opposite: profligate waste and clumsy distraction.

It was six in the morning last Sunday; I lay in bed, listening to the ticking of the ignition on my Viking’s pilot light. There was the sound of running water, the clank of a pan on a burner. When my mother came to visit us last weekend and awoke in the throes of pre-dawn Bad Mood, she rifled through our refrigerator, pulled out four eggs, set them in shallow water, turned the burner on high, and cooked them until they burst with fury.

” I couldn’t sleep,” she barked from the guest bed where she’d laid back down after preparing the breakfast she decided I needed to eat, “so I made you eggs. THIS is what you should be eating for breakfast—not the heel of a baguette and a piece of cheese.”

She had been watching me that closely the previous morning; to my mother, a piece of bread — no matter how small — spells o-b-e-s-i-t-y. She was in a rage.

“But I don’t have any eggs,” I answered, suddenly remembering the half-crate of six local duck eggs that were hovering in the back of the fridge, waiting for a recipe test.

“They’re in the SINK—” she shouted from the guest room.

I walked into the kitchen and there they were, in a now-dry All-Clad saucepan, the shells cracked and broken, their whites extruding like Elizabethan collars. Susan broke one into a cup to see if the yolk was hard-cooked, and somehow salvageable; it was raw and cold. The eggs had been sitting out at room temperature for over two hours.

My mother marched into the kitchen behind me and watched Susan put on the tea kettle; I stepped on the pedal of the trashcan and tossed each duck egg out, one by one, like small grenades.

Fried Duck Egg with Toast and Truffle Salt

It doesn’t matter if it shoots forth from a hen, a quail, a goose, an emu, an ostrich, or a duck; an egg is a tender and potent harbinger of optimism. When Willem Dafoe carries a precious, stolen one to Juliette Binoche, ensconced in Villa San Girolamo at the end of World War II in The English Patient, it signifies hope and humanity. Having lost his thumbs to torture, Dafoe drops it, and we know the war isn’t yet over. Treating an egg badly — wasting it, misusing it, using some of it but not all of it — feels, at its very core, malicious, inhuman, wrong. Sad. Treat it well — poach it, fry it, boil it — with focus and attention, and it means hope.

Duck eggs, to me, are special; now that I’ve had the experience of singing to the chickens who live next door, their eggs are special too. Duck eggs are just, well, eggier; I like to serve mine on toast that’s been lightly coated with tapenade, and then carefully sprinkled with good truffle salt.

Serves 1

2 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil

1 duck egg

1 tablespoon prepared tapenade

2 toast fingers, kept warm

pinch of truffle salt

freshly ground black pepper

Heat the olive oil in a medium frying pan over medium high heat until it begins to ripple; break the egg into the pan, cover, and cook until the edges are golden and the yolk has just set, about 4 minutes.

While the egg is cooking, spread the tapenade on the toast points. Serve the egg on top of the toast, and sprinkle with the truffle salt, and a light grinding of freshly ground black pepper.