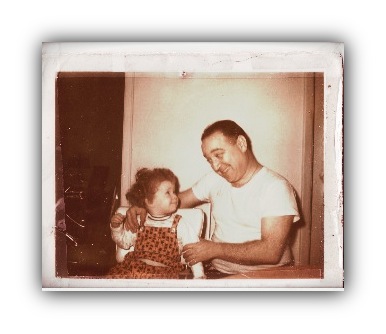

He taught me about mother sauces and Coleman Hawkins, and that gin Gibsons are best when tongue-achingly dry and served in antique glasses. He taught me that the noise of the city can be soul-killing, and that attachment to trend can damage the human psyche at its very core. A former Navy fighter pilot, he taught me that the constellations on the ceiling of Grand Central Station were accidentally installed upside down and backwards. He taught me to love lobster, and took me and a few friends out for my sixteenth birthday to a French seafood palace upholstered with padded ruby silk dupioni wallpaper that made the place look like a New Orleans bordello; when one of us indelicately pried a piece of thick knuckle meat out of its shell and it flew across the room and bounced off the wall next to the light switch, he told the sneering server that the lobster was clearly old and rubbery, and never should have made it to the table. My father taught me that old things — old jewelry, old music, old art, old beaten-up guitars — are almost always better and sweeter, than new. But he drew the line at lobster, and felt that it was never fair to eat the bigger ones who had somehow managed to avoid the trap by will or luck for so long.

He taught me about mother sauces and Coleman Hawkins, and that gin Gibsons are best when tongue-achingly dry and served in antique glasses. He taught me that the noise of the city can be soul-killing, and that attachment to trend can damage the human psyche at its very core. A former Navy fighter pilot, he taught me that the constellations on the ceiling of Grand Central Station were accidentally installed upside down and backwards. He taught me to love lobster, and took me and a few friends out for my sixteenth birthday to a French seafood palace upholstered with padded ruby silk dupioni wallpaper that made the place look like a New Orleans bordello; when one of us indelicately pried a piece of thick knuckle meat out of its shell and it flew across the room and bounced off the wall next to the light switch, he told the sneering server that the lobster was clearly old and rubbery, and never should have made it to the table. My father taught me that old things — old jewelry, old music, old art, old beaten-up guitars — are almost always better and sweeter, than new. But he drew the line at lobster, and felt that it was never fair to eat the bigger ones who had somehow managed to avoid the trap by will or luck for so long.

“The elderly should never succumb to the whims of eating contests or rich mens’ wallets,” he once said, philosophically, while we walked around Portland, Maine one weekend in the ’80s, watching the lobster boats come in. Hardly old, he had just turned sixty five and had already survived a quadruple by-pass and the Rotor-Rootering of both his carotid arteries after a lifetime of significant pastrami consumption. It’s not so much the years, he added, as the mileage. My father had become sensitive to ageism, even where crustaceans were concerned.

I wasn’t really thinking about Father’s Day a while back when I decided that Maine would be a good place for my family and me to perch for a week while I focused on a new book project. Susan and I rented houses in Vermont for years, but somehow, we needed to go further north this year, where things were quieter and a little wilder. We initially planned to go around the week of my birthday — at the end of June — but the house wasn’t available, so we wound up going earlier to this place built on an outcropping overlooking Atkins Bay, high over the water.

We packed the car like Tom Joad: a small library of books, some good wine, a pile of shorts and tee shirts, my computer (which would not work; there was mercifully no WiFi anywhere in the area), and my beloved 00-18 Martin guitar, in the hope that I’d have the time and inclination to play. It’s the secret that no one knows, and the one I never talk about: I am a guitar whore. I’ve been playing since I was four, and my father coddled and nurtured my affection from the time I started to play: he’d learned about old timey and bluegrass during World War II while stationed in Texas, and the heart in that music bit him hard. He built my collection of Bill Monroe albums piece by piece, hauled me and my enormous dreadnaught all over New York to play in the folk music festivals of the 1970s with musicians three times my age, and took me on four separate occasions — once with a raging fever that I didn’t know he had until we got there — to see Doc Watson, back when Merle was still alive.

“You need to play more,” Susan said to me a few years after my father’s accident in 2002. “He’d want you to.” After he died, I all but stopped. I stopped listening to bluegrass, and stopped being so freakishly connected to this music that he loved, that had replaced the jazz of his bachelor days, and the Chopin Etudes of his youth, and which culturally belonged to neither of us. And I knew that it wouldn’t have made him happy. I did not expect to go out shopping for lobster on Father’s Day in Maine almost ten years after his accident, and end up in a dusty music store with my hands wrapped around an old, very cheap, Airline model F-hole archtop guitar — Montgomery Ward sold them in the 1950s and 60s — playing Bury Me Beneath the Willow. The guitar is funky and a lot beaten up, and someone probably loved it a very long time ago until it was discarded for something newer and maybe a little bit flashier. Or perhaps it sat forgotten in someone’s closet until it was discovered by someone else, more than half a century later. Who knows.

“Go ahead—“ Susan said, handing me my wallet. “But you just have to promise me you’ll play it. Happy Father’s Day, honey.”

We stopped for two small lobsters on the way back to the house, boiled and then braised them quickly in white wine with spring onions and fresh peas from our garden that we picked right before we packed the car at home; we drank a gin cocktail toast to the most important men in our lives who we lost way too early. And after dinner was over and the dishes were done, I sat on the deck overlooking Atkins Bay, and played my new, ancient guitar late into the night, marveling at the sweetness of its age.

Braised Lobster Paella with Fresh Peas and Wine

The older I get, the less comfortable I am with the idea (or act) of killing a lobster, or pretty much anything, however directly or indirectly; I can’t quite make the ethical connective leap from pissed off crustacean to puppy, but I’m guessing that will happen in the future. Still, when I’m in Maine, I’ll make lobster because it seems slightly sacrilegious not to. I don’t generally like to dither with tradition, but I envisioned this paella-ish dish as sort of a soupy/sloppy rice made with long grain rice instead of Calasparra or Bomba. To further annoy my cheffy friends, I used brown rice because it was all I had access to, without driving half an hour into nearby Brunswick, Maine. The result was everything I wanted it to be: warm, comforting, and a perfect combination of earthy and sweet. If you have leftovers, bind them together with an egg or two, shape into patties, and pan-fry them in a stick-proof pan.

Makes 3 servings with leftovers

2 small lobsters (no more than a pound each)

1 tablespoon extra virgin olive oil

1 cup long grain brown rice

¼ cup minced spring onion, white part only

2 cups vegetable or lobster stock

1/2 cup mildly fruity white wine (Albarino is perfect)

½ cup fresh peas

½ cup fresh snap peas, tipped, and sliced on the bias

fresh parsley, chopped

To cook the lobsters: bring a large stock pot of water to boil over high heat, and plunge the lobsters in head-first. Cover and cook for 8 minutes. Remove the lobsters and when cool enough to handle, extract the tail and claw meat, chop into chunks, and set aside. Place the shells and pereiopods (the small “walking” claws on either side of the body) in a heavy duty zip lock bag and freeze for stock.

Heat the olive oil in a deep 10” skillet until it begins to shimmer, and add the rice and the onion. Cook until the rice begins to toast and the onion turns translucent, stirring constantly for about 5 minutes, stirring constantly. Pour in the stock, stir well to combine, lower the heat so that the liquid is barely simmering, cover, and cook until the rice is tender but still toothsome, about 30 minutes.

Remove the cover, add the wine and the reserved lobster meat, and continue to cook until the rice is done, another 8 minutes or so. Fold in the peas and the parsley, and continue to cook until the snap peas are tender. Serve immediately.