Deep-fried turkey. Remember Chernobyl?

This is the first time in the last ten or so years that I won’t be spending the early part of Thanksgiving day on the phone, in a live radio broadcast where I answer last-minute, rapid-fire holiday cooking questions for regional NPR listeners far and wide. Last year, Susan and I were in Florida at my cousin Carol and Howard’s new house, where I squirreled myself away in their guest cottage and spent a solid hour on the phone, fielding questions for a slew of overwrought listeners of Wisconsin Public Radio, all of whom seemed to be involved in making Thanksgiving dinner for big crowds. A few years earlier, I did the same kind of call-in show for a different affiliate, while sitting in Carol’s sister and brother-in-law Nina and Robert’s house in northern Virginia. I had my notes at hand; the only problem, I laughed to Susan, would be if someone called in asking about lentil nut loaf.

And then, of course, someone called in with a question about lentil nut loaf.

“It’s always very dry,” the caller whined, “every single time I make it. Everybody hates it. Nobody will go near it–” she sighed. “Can you help?”

“Possibly,” I replied. “But why do you keep making it?”

“Because it’s a family tradition,” she answered, exasperated.

“But they hate it, you said—”

“It’s family tradition—don’t you understand t-r-a-d-i-t-i-o-n?”

Of course I did, I said. And I do. But if her whole family loathed it and it was dry and heavy as a brick, I suggested that she might want to try something a little bit different, like maybe a millet bake. Or perhaps quinoa croquettes laced with herbs and chard.

“That,” she answered curtly, “is not my family’s tradition.” And then she hung up.

During another call, a man told me that he enjoyed serving macaroni and cheese at Thanksgiving, but he wanted to put his own little spin on it.

“What are you thinking?” I asked.

“Well, how about using different cheeses—” he replied. “Do you have any suggestions?”

Being a big fan of macaroni and cheese as a way to give thanks at any time of year, I suggested my favorite three-cheese combination: an eye-wateringly sharp cheddar, Parmigiana Reggiano, and Gruyere.

“I could never do that—” he gasped.

“Why not?” I asked.

“Look lady, you honestly expect me to use French cheese during the most American of holiday dinners? Who did you vote for in the last presidential election?”

Click.

And so, after ten years of pre-Thanksgiving radio call-ins with exhausted, emotionally depleted folks who are cooking for crowds of people, some of whom may be grateful, and some of whom may just be showing up for the meal before passing out on the couch in a Tryptophan haze, this is the thing I’ve discovered about Thanksgiving dinner: no matter how creative we believe we want to be, we really don’t actually want to be. We want what we want, and even if we’d like to think we’re open to the power of suggestion, what we want is tradition, because tradition makes us feel safe and secure. Add bourbon to the brine and then you get to worry about your Aunt Gertrude, who can’t get near alcohol, going on a bender. Add a dash of Worcestershire sauce to the stuffing to up the umami factor, and you get to worry about your cousin Louise’s throat closing up on account of the anchovy.

“But I was just trying to up the umami factor,” you shrug to her husband, Dave, as the EMS guys pump Louise full of adrenaline before loading her into the ambulance.

“Up your own umami factor,” Dave snarls, zipping up his coat.

These are the dangers of screwing with tradition on this most traditional of holidays; it rankles people. It gives them turkey shpilkes. Going all fancy-ass during Thanksgiving is really not about your guests, and how well you want to take care of them; it’s all about you, and when you’re serving people, it really shouldn’t be. Honestly, despite all those wonderful food magazines (some of which I write for, in the interest of transparency) hawking fresh, new flavor-forward ways to deal with what essentially is an overgrown game bird that instantaneously takes on the consistency of balsa wood if you overcook it for eight seconds, most people just want simple. They want what they know. They want tender and juicy and flavorful (who doesn’t?) and they don’t want anything too weird, or unrecognizable, or alien. If your family’s tradition for the last fifty years involves pre-packaged stuffing, so be it; you can bet the house that people are going to get their knickers in a twist if you haul out oyster dressing, no matter how delicious it is. (And it is.)

But don’t people want to be adventurous? Don’t they want to try something new and even trendy? Yes, they will often say; they do. Or at least they think they do. But Thanksgiving tends to be as emotionally fraught as it is laden with family culinary tradition, so people want to eat the equivalent of a security blanket. This is why the minute the sweet potato pie with the marshmallows comes out of the oven, everyone runs in to the kitchen to start picking at the burnt ones, the way they did when they were six. It makes them feel better.

So, gird your loins: the day is soon upon us. And regardless of whether you’re roasting a fancy Spanish Black turkey or some other heritage breed, or you’re festooning a supermarket bird with white paper anklets, there are some universal truths to consider:

1. Nobody wants a dry turkey. Which means that it’s better to buy two small turkeys (under ten pounds each) instead of one big one the size of a Volkswagon. If you buy two small turkeys, you can roast them the way you would a roast chicken. I generally tend to think that smaller birds are less prone to dryness simply because they cook more evenly, assuming you let them come to room temperature before roasting; you baste them regularly; you start them breast-side down and rotate them as they cook, and you let them rest for a full thirty minutes before carving them.

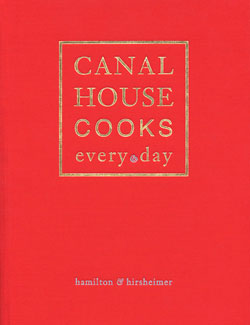

If, however, you do want to go down the big turkey route but you’re still looking for a recipe that’s decidedly non-fussy and totally delicious, here is Christopher Hirsheimer and Melissa Hamilton‘s dry-brining and roasting instructions from their remarkable Canal House Cooks Everyday, which should stand in every American home kitchen right next to the pepper mill. This book is a keeper, and when you’ve spattered every single page with oil and fat and wine, don’t worry: it’s meant to be that way. (Their recipe is below.)

If, however, you do want to go down the big turkey route but you’re still looking for a recipe that’s decidedly non-fussy and totally delicious, here is Christopher Hirsheimer and Melissa Hamilton‘s dry-brining and roasting instructions from their remarkable Canal House Cooks Everyday, which should stand in every American home kitchen right next to the pepper mill. This book is a keeper, and when you’ve spattered every single page with oil and fat and wine, don’t worry: it’s meant to be that way. (Their recipe is below.)

2. The hell with spatchcocking. (This is not a dirty word.) Spatchcocking is the turkey roasting trend du jour, and all it means is turning the bird (any bird) over onto its breast, snipping out its backbone with a good pair of kitchen shears, turning it back over, and flattening it (the process is also called butterflying) prior to cooking. I spatchcock chickens and poussin regularly because it reduces their cooking time, and I strongly recommend it. But Americans as a people like to do things BIG, and despite instructions not to, we all know that a bunch of folks are going to be out there wrestling with a twenty-two pound bird and a pair of shears, which will be a little bit like snipping out the undercarriage of a Volkswagon (see above). Do not attempt to spatchcock birds over nine or ten pounds, max. Remember the wrestling scene in The World According to Garp? Watch it.

3. Buy the very best fresh, local bird you can afford: This makes a huge difference. Those giant Butterballs that are always on a deep sale right before the holiday? Think they’re all from this year? Maybe so. Maybe not. Find a great local turkey farm and order the bird well ahead of time. A month or so ago, I had the pleasure of visiting the Diestel Family Turkey Ranch in Sonora, California to see their operation, courtesy of Whole Foods; right before I left, one of the nice Diestel men threw a lightly marinated, fresh turkey breast on the grill. I expected shoe leather. It was tender, succulent, and probably the very best turkey I’ve ever tasted. It pays to buy local and know the product you’re getting.

4. Brine the bird: Dry brine it (like Christopher and Melissa do), or wet brine it. No matter what you do, though, brine it. Forget about brining it in maple syrup or tequila or kumquat juice. To wet brine it, combine two gallons of water (or enough to completely cover the bird) with 1-1/2 cups kosher salt and 1/2 cup brown sugar and the herbs of your choice. To dry brine it, follow the instructions in the recipe below. Simple is best.

5. Bring the bird to room temperature before you roast it: Trust me; it’ll cook more evenly, and no one wants an unevenly-roasted turkey. (This also goes for chicken, and pork, and lamb, and beef. And no, letting it come to room temperature will not make you sick.)

6. Let the bird rest for 30 minutes before you carve it: Possibly the most important key to a tender, juicy bird. Take it out of the oven when it’s done, let it rest on its rack, lightly draped with foil. Keep the knife-wielding men-folk out of the kitchen, lest they have at it and all that luscious turkey juice runs right out of the bird and on to the floor.

Roast Turkey

copyright Christopher Hirsheimer

We’ve cooked turkeys every which way: in a brown grocery bag (turns out to be highly unsanitary), draped with butter-drenched cheesecloth, deep fried, deboned and shaped into a melon (oh la la!). We’ve even wrestled with a hot twenty-fve pounder, breast side down, then breast side up, and on and on. But we think we’ve found the answer to achieving the perfect Thanksgiving Turkey — the easy dry salt brine.

Rinse a 14–16-pound fresh turkey (not injected or pre-brined) and pat dry with paper towels. Rub or pat 3 tablespoons kosher salt onto the breasts, legs, and thighs. Tightly wrap the turkey completely in plastic wrap or slip it into a very large resealable plastic bag, pressing out the air before sealing it. Set the turkey on a pan breast side up and refrigerate it for 3 days. Turn the turkey every day, massaging the salt into the skin through the plastic.

Unwrap the turkey and pat it dry with paper towels (don’t rinse the bird). Return the turkey to the pan breast side up and refrigerate it, uncovered, for at least 8 hours or overnight.

Remove the turkey from the refrigerator and let it come to room temperature, at least 1 hour. Preheat the oven to 325°.

If you’ve decided to serve your turkey stuffed, spoon the stuffing of your choice into the cavity of the bird. (Put any extra stuffing into a buttered baking dish, cover, and put it in the oven to bake with the turkey for the last hour.) Tie the legs together with kitchen string. Tuck the wings under the back. Rub the turkey all over with 3–4 tablespoons softened butter.

Place the turkey breast side up on a roasting rack set into a large roasting pan. Add 2 cups water to the pan. Roast the turkey until it is golden brown and a thermometer inserted into the thigh registers 165°, about 3 hours for an unstuffed bird and 3–4 hours for a stuffed one.

Transfer the turkey to a platter, loosely cover it with foil, and let it rest for 20–30 minutes before carving. Serve the turkey and stuffing, if using, with the pan drippings.