“On the one side is your happiness and on the other is your past — the self you were used to, going through life alone, heir to your own experience….You take one timid step forward, but then you realize you are not alone. You take someone’s hand … and strain through the darkness to see ahead.”

— Laurie Colwin, Lone Pilgrim

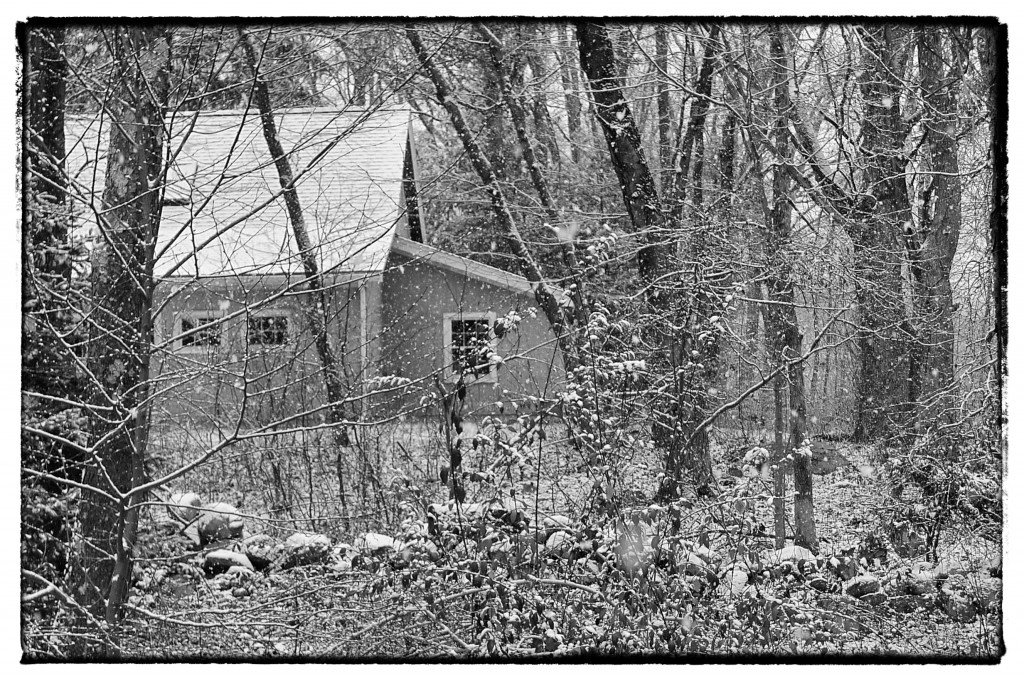

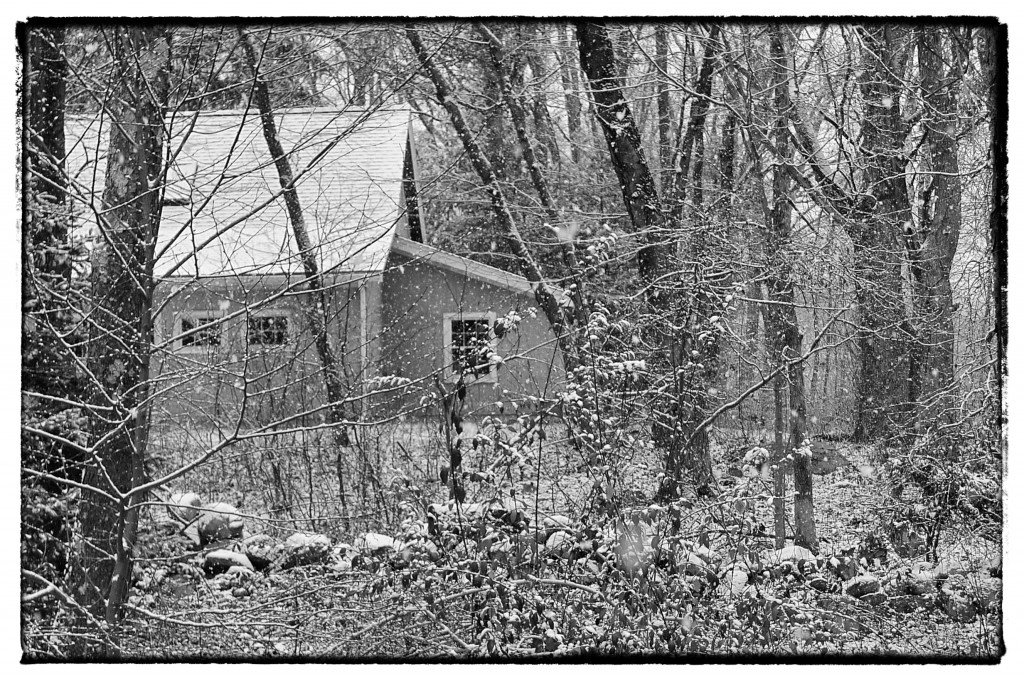

There’s something about the grayness this time of year that makes me alternately giddy and wistful; I long for days that arrive quietly, lightly dusting the yard and the garden with snow. They compel me to work at my desk or in the kitchen in complete silence, with the dogs sleeping soundly in the next room. I leave the radio off and shudder when the phone rings. It’s always at this time of year when I consider cutting off our television service; we don’t watch football, we get our news from NPR and the paper, and everything else — old movies, new movies, Downton Abbey, Portlandia — can be had on demand, making the constant drone of 2000 digital channels of nothing feel like an assault. Maybe it’s just the impending end of fall, with its run-up to the holidays and its psychic noise of must-haves and must-dos and must-cooks, its expectations and attending promises of warmth and cheer, its sentiments and happy childhood memories that many of us try and recreate with a grievous, almost panicked fury.

Once, when I was twelve, my best friend gave me a Victorian charm, which she’d purchased in an antique store while shopping with her mother for Christmas. She had a set allowance for me and her little brother, and when Lucy handed me the tiny box on Christmas morning — I always spent Christmas with her family since my parents didn’t celebrate — I opened it and gasped. Fashioned from rose gold, the charm was a simple rendering of a reindeer. I loved it not only because it was deeply personal — somehow, Lucy knew instinctively that I would love something that had been cherished by someone else many years earlier; even now, I prefer, and dote on, much older things from cookware to guitars — but because it was enveloped in all the meaning of the season, so far as my prepubescent brain could understand it: here was something mundane that had been quietly chosen for and entrusted to me, without suggestion of screeching advertisements or newspaper circulars. It meant thought, and love, and care, and on some unfathomable level, peace.

Years later, when we were in college — I, in Boston, and Lucy, in Manhattan — it became obvious that we were going to lead very different kinds of lives; we tried to cling to the friendship that we’d had as children, but it hadn’t grown with us. It was sad when we both realized it, and we just stopped trying. I removed the reindeer charm — which I’d taken to wearing all year as a kind of anchor — from my gold chain, and wrapped it up in royal blue tissue paper. It sat in my jewelry box for almost two decades, dragged through the early days of my adulthood in New York, from apartment to apartment, out to Brooklyn, back to Manhattan, and finally, up to married life in Connecticut. I never wore it again, but the first time Susan and I decorated a tree together with the antique striped glass balls and cut-out paper ornaments of her youth — each ascribed a special memory and meaning — I slipped a small metal hook through the charm’s loop and hung it discreetly and almost imperceptibly amidst my partner’s connection to her Christmas past; I’ve done it ever since, for the twelve Christmases we’ve shared. Lucy — who we were as children — is still very much a part of my holiday, frozen in time.

And this is what most of us do during big holidays like Thanksgiving and Christmas. We haul out memories and connections to who we once were, we acknowledge them, and then we tuck them away again when the holiday is over. On the first night of Hanukah, I make my Grandma Clara’s potato latkes and call my mother, who says “you’re making Grandma’s lockets?” (She says it, every single time.) I can see my grandmother in our kitchen in Forest Hills; I can smell her — a heady combination of Jungle Gardenia and Aqua Net and Wesson oil — and I feel her standing beside me, even though she’s not. We try, every holiday, to recreate the Swedish meatballs that Susan’s beloved (non-Swedish) grandmother made, and which the entire family adored; every year we fail, but it’s in the making of them — the almost meditative thinking and remembering how they tasted and what their consistency and color of the sauce was — that brings her back to Susan, if only for that moment. It matters not a whit if they don’t come out right; that’s not what cooking to remember is about.

Every Thanksgiving, my cousins and I try, sometimes subconsciously and sometimes not, to recreate our most important fall holiday of years ago, when we were all together at my aunt’s house, when the “children” — all of us adults entering or well into our forties — were happy and safe, and aunts and fathers and uncles and grandparents and brothers were all alive, and the house rocked with the roots music that my late cousin Harris and I played for hours on end before my aunt rang a trio of tiny Swiss cowbells — they now hang in my cousin Mishka’s house — to let us know that dinner was ready. We work very hard it seems — sometimes painstakingly so — at recreating this event, squinting back into the past to remember and feel and smell and taste exactly what it was like. Sometimes, we succeed. Sometimes, the striving to recreate something that doesn’t really exist anymore stresses us into a kind of psycho-culinary hysteria. Sometimes, our attempts at producing this meal which my aunt created for years with apparent effortlessness, go awry, and we’re all over each other like a bad suit. And sometimes, as was put to me plainly last week, the family circle simply gets re-drawn when we’re not looking; suddenly we’re Scrooge, blowing the snow off the windows of time so that we can peer in from outside for a sharper look at Fezziwig dancing in front of the fires of our past, as the wind howls around us.

There’s nowhere to go but forward, into the future.

On the Friday after Thanksgiving this year, Susan and I drove out to rural northwestern Virginia to visit a new friend and her boyfriend, who live way off the beaten path in an old miller’s house built between the 18th and 19th centuries. Spare, quiet, and with a long, homemade rectory-style table running the full length of the dining room, the place was a balm to my jangled holiday nerves; I sat down in front of the roaring fire to catch my breath, and before we left, Sarah handed me a small crate filled with eggs laid by her chickens and the two (hilarious) Indian runner ducks who patrol the property.

Happy Thanksgiving, she and Ben said, as we hugged them goodbye and gingerly placed their gift — eggs are harbingers of the future, symbols of eternal optimism, promise, and possibility — into the cooler in our trunk, and drove back to my cousin’s house. We returned home to Connecticut the next day, and I put Lucy’s reindeer back on my gold chain as a tether to the me who wore it years ago, back before the days of worrying about heritage versus conventional, brining versus not, how many squash dishes to serve, who is going to be upset and cranky if I cook and who isn’t, where and with whom to have Thanksgiving dinner, or even what side of the circle I’m on. We fried Sarah’s duck eggs tenderly in an ancient cast iron pan, and talked about my darling cousins (who, with Mishka’s second baby due in May and my cousin Russ getting married in June, are quickly increasing in number) and our friends who we love so much and don’t see enough of. And how, as the years pass and we all move forward and begin to shape and form our own holiday traditions — taking what we can from the past, honoring it, but then making it our own — our circle has also been re-drawn, only it’s gotten bigger. There’s room for everyone.

We wouldn’t have it any other way.

A Fried Duck Egg on Toast

Anyone who is a regular reader of Poor Man’s Feast knows that all my life, I’ve had a small love affair with eggs of every kind: chicken eggs, pullet eggs, quail eggs, caviar. More recently, I’ve fallen head over heels for duck eggs, which are now much easier to find than they used to be. Generally, they’re a good bit larger than a jumbo chicken egg, a lot (in my estimation) earthier, and I think far more precious (the duck clearly thinks so too, perhaps accounting for why the shell is harder to crack than its chicken counterpart). When Sarah gave us the gift of eggs from her birds on a day that saw me mired in the past, in old hurts and ancient memories, they lifted my spirits. And prepared as simply as possible, that’s what eggs do. We had ours for dinner recently, with a glass of wine and a small green salad.

Serves 1

1-1/2 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil

1 duck egg

1 thick slice country bread

1 pinch sea salt

black pepper to taste

In a very well-seasoned, small cast iron pan, heat one tablespoon of olive oil over medium heat until it just begins to shimmer. Gently crack the duck egg directly into the pan, taking care not to break the yolk. While the egg is cooking, toast the bread.

Cook the egg for four minutes without moving it; the edges of the white should go crispy and brown. When they do, gently tilt the pan and spoon some of the hot oil directly over the yolk. Top the toast with the egg and drizzle with the remaining oil. Season with salt and pepper and serve immediately. Hot eggs wait for no one.