It’s been a while since I’ve written, and I could come up with every excuse in the book: I’m getting ready for an extensive Poor Man’s Feast book signing tour in March and April (dates to come; I’m starting out west in some of my favorite spots in the world, and I hope to see many of you and have the chance to thank you for reading in person); my day job as an editor has gotten very busy; I’m writing a new book (more on that later; it’s a bit surprising although not in a Fifty Shades way); I had the flu; Susan had the flu; now my mother has the flu. All of these excuses are valid, certainly. Still, I feel like my Life, cap L, has started to run amok, like it’s a separate, stand-alone entity with a mind and Filofax all its own. This is what happens, I guess, when you don’t pay attention to the immediate life, small L, that is your existence; instead, you get sucked into a vortex that keeps you spinning like a Dervish and struggling to keep your head above water until you pass out in bed each night and wake up the next morning to start all over again. Rinse, repeat.

I’ve been reading a lot lately about something called shenpa, which translates more or less to “attachment.” Pema Chodron explains it more accurately as “getting hooked.” It’s a sticky feeling, she says; for me, it’s that old familiar grind that I get in the pit of my stomach that churns and growls when someone says something mean or outrageous to me, even if I know deep down that it’s their mishegas that’s causing them to say it, as opposed to my own (and believe me, I have plenty). I want to fix them, or help them, or just make things right, dammit, and I lay awake nights, worrying, propelled by a kind of psychic adrenalin rush. Shenpa is an unspecific compulsion, and therefore can be relatable to anything; it’s like not being able to scratch an itch, or not being able to refuse a drink if you’re an alcoholic, or not being able to keep yourself from getting engaged and sucked-in. You take the bait, whatever that bait is, and you’re off and running. Shenpa is a taxing, raging, unforgiving beast: it’s the devil on your shoulder. It’s like running a marathon while chained to a boulder. Forget about your day job — if you’re stuck in a shenpa-driven cyclone, there aren’t enough hours; there isn’t enough energy coursing through your veins. Best to step off the track, to pause, to breathe.

I know when shenpa has me by the throat by the way I cook, and the way I interact with Susan. My brain goes elsewhere; I go through the motions. Standing at the stove, I get distracted by something; suddenly, I absolutely have to check my Facebook page, or my Twitter feed, or my email to make sure that that person I’m engaged with in a psycho-emotional digital drama hasn’t responded, because then I have to respond. I’m making dinner for us, and those gorgeous pork chops (from the local spotted pig we had raised and slaughtered for us, and for which we had to purchase an expensive upright freezer) that are sitting in the blazingly hot, 1932 Griswold skillet we inherited from Sue’s Aunt Ethel cook for a split second longer than they should because I wasn’t present in either mind or body. Shoe leather. Very expensive, artisanal, locally-raised, hormone-free shoe leather. Susan has lit the candles and set the dinner table with our pearl-handled Laguiole steak knives, which can’t even saw through the meat. She smiles and touches my hand and tells me it’s really okay. Honoring the pig and all that? Yeah. I’d really like to, I think to myself, but I can’t right now.

Shenpa, you crazy bastard, how are the kids?

Thirteen years ago this weekend, Susan and I went out on our first date; we found each other on-line and corresponded for three solid months before meeting, which contradicts Timothy Egan’s assertion in his recent New York Times blog post, The Hoax of Digital Life, that on-line dating is “only the start of what led us down the road” of “commitment-free, surface-only living.” We were both proceeding cautiously: my last serious relationship — with a highly conflicted physician — had ended disastrously ten years earlier. Susan’s, also disastrous, had come to an end more recently. And while all of the people I met on line (unlike Manti Te’o‘s poor deleted girlfriend ) actually existed, they were not without their issues: one was married (to a man) with three children. Another chained her ancient Bichon to her radiator every night — just out of reach of her water bowl —to keep it from wandering around her apartment and peeing on her couch. Another was looking, she told me, for just a plutonic relationship. And then, there was Susan.

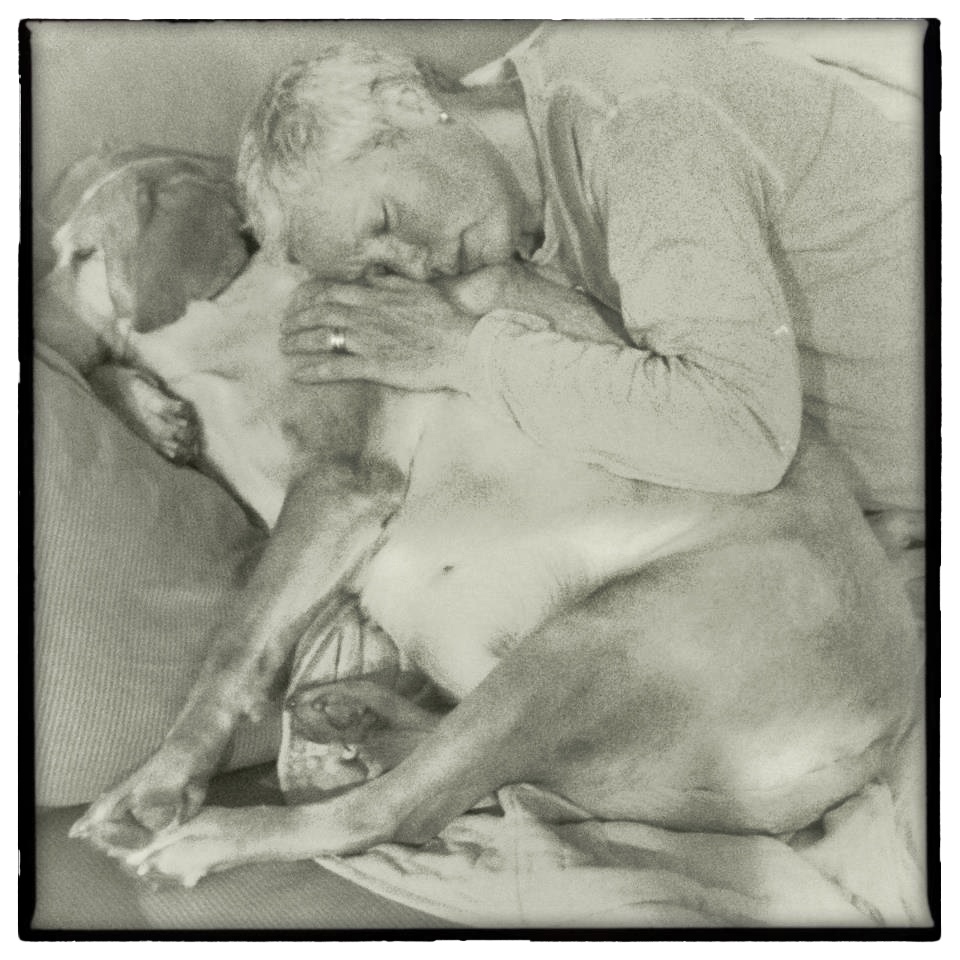

She was simultaneously shy and hilariously funny. She had a large dog — a Curly Coated Retriever named Macgillicuddy — with whom she shared her breakfast tea (lightly sweetened, with milk) and who, when she shook her head, would launch long strands of drool onto anything or anyone that happened to be nearby. Susan read Jane Kenyon and Donald Hall and M.F.K. Fisher, and kept an ancient, threadbare copy of Larousse Gastronomique on her nightstand. She had been a charter subscriber to Saveur, and remembered that Peggy Knickerbocker had written the article about the Old Stoves of North Beach. She loved stinky cheese, and simple food. She was in publishing, like me; we had mutual friends who never thought to introduce us. Eventually, we discovered that we had seen each other before — in 1986 — on a softball field (where else?) in Central Park, where my team (Avon Books) was being trounced by her team (Dell Books), and I had laughed at her because she was wearing bright red Sally Jesse Raphael glasses and matching knee braces.

It was a bitterly cold Saturday afternoon in 2000 when Susan and I finally met, at the Paley Center for Media in Manhattan; we sat through episode after episode of very early I Love Lucys — the ones with the Philip Morris ads — and had dinner that night at Titou, in Greenwich Village. Over cassoulet and duck confit and wine, we discovered our mutual fanaticism for roots music — we loved Hazel and Alice, and Emmylou Harris, and Ralph Stanley. She discovered that I hated beets; I learned that she hated cilantro although she adored Vietnamese food, which I found peculiar. And when we met the next morning for brunch at Christine’s Polish Kitchen in the East Village, we sat for four hours over plates of kielbasa and pierogi and eggs.

I can tell you what she was wearing (dark blue cable knit sweater). I can tell you the exact color of her eyes (green). I can tell you that we developed a sort of tunnel vision that morning; we couldn’t hear anything or anyone else around us, and when Svetlana, our nice Polish waitress with the white blonde braids asked us if we wanted more coffee, she had to repeat herself twelve times before we heard her. And I can tell you that when Susan noticed a tiny, quarter-inch long scar at the base of my right middle finger (the result of a freak accident when I was in sixth grade), I was done for.

Cooking for someone you love — planning what to make; shopping; standing in the kitchen and mincing and dicing and chopping with focus and undivided energy and attention — this is the very opposite of shenpa; it’s a presence of life and brain and heart that nothing can disrupt — not Facebook, not Twitter, not email, not some weird psychic energy suck that threatens to ensnare your mind and refocus your attention on things that don’t really exist. After that brunch, I knew that I wanted to cook for Susan and Susan alone, every day, and every night. I wanted to cook well, with love, and attention. And the following weekend, I did. I have, ever since.

Mostly.