Even while I’m fighting a horrible case of the flu/bronchitis (it’s probably, in fact, a rare strain of Ebola that no one has figured out how to treat yet), we’re presently de-cluttering for the holidays, which is no easy feat for us; we’re definitely both pack rats. And because we’ve both been in and out of publishing for years — twenty-five for me and thirty for Susan — and because we both could live in the kitchen (to the degree that we’re considering tearing a wall down so that we actually are living in the kitchen), and because I used to be a bookseller specializing in cookbooks, and because I edit cookbooks, and because I’ve also been writing about food for the last fourteen years, we are literally surrounded by cookbooks. They live everywhere: in the kitchen, the den, the living room, the bedroom, the guest room, the two bathrooms, the basement, my office, and the garage. This makes de-cluttering sometimes emotionally wrenching (I don’t want to get rid of any of them) and challenging, as you might expect.

What’s even more challenging, though, is the fact that this particular time of year is when all the great new cookbooks come out that publishers hope and pray will hit the holiday “roundups.” So even while we’re in the midst of clearing out, I’m simultaneously bringing home holiday gift books — there’s a fabulous bookstore in Grand Central Station that I find terribly alluring — and squirreling them into the house, hoping Susan won’t notice.

It’s just a small addiction. Like what Janis Joplin had.

What’s that? Susan asks.

What? I answer.

That book. I don’t remember it, she says.

We’ve had it forEVER, I say.

She rolls her eyes and walks away.

Of course, the most ironic thing is that regardless of how many cookbooks I have and no matter how enticing they are (I stay away from books about cakepops and cupcakes and candymaking; I have absolutely no sweet tooth), I tend to make the same things over and over again. I think this is a truism that people don’t generally talk about. That union in the Venn Diagram that plaits people who cook to people who buy cookbooks is ultimately comprised of people who cook and who buy cookbooks and who make the same ten things over and over again from the same cookbooks, no matter how many new cookbooks they buy.

There should be a retail category for this, or at least a coded diagnosis in the DSM V.

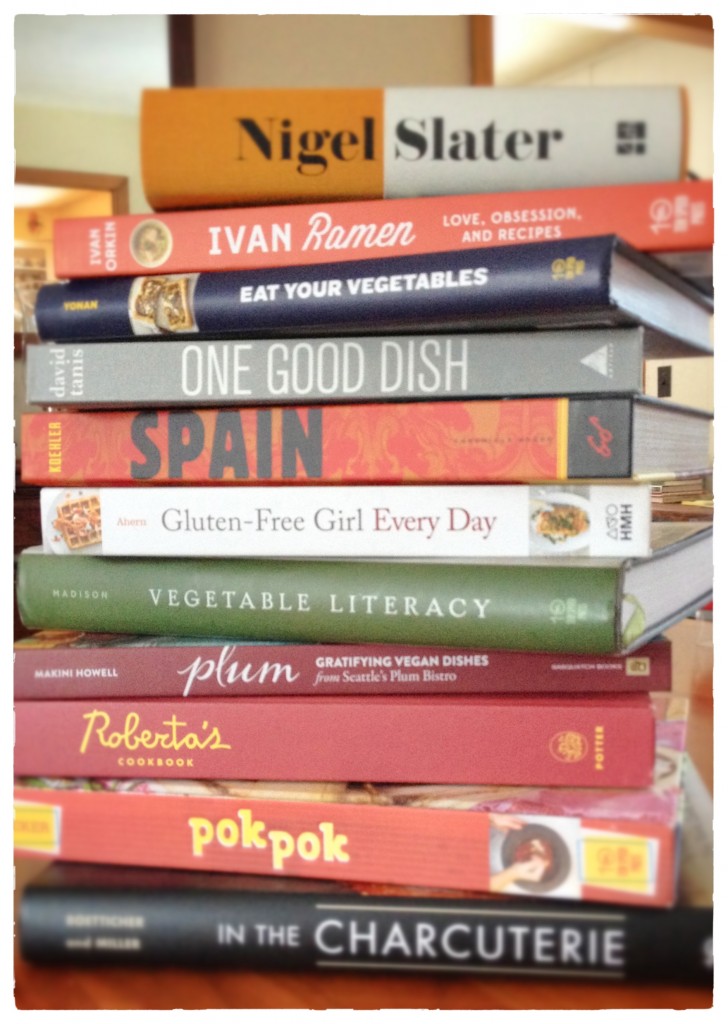

The question, then, is why do I need more cookbooks? Do I really need them at all if I’m making the same things over and over from books that are splattered and spine-cracked and reeking of (in the case of The Zuni Cafe Cookbook) mock porchetta filling? Hell yes, I do. Because if I didn’t have Hawksmoor At Home, for example, I wouldn’t have suddenly fallen in love with IPA Shortribs, or Grilled Smoked Eel with Celeraic Remoulade. And that would be a pity. If I didn’t miraculously come across Lucas Hollweg’s Good Things to Eat at Rabelais Books in Maine and immediately have to have it, I never would have discovered his bean soup with cabbage and bacon. Or his pile of tiny roast quail in a bowl, eaten with one’s fingers (the way quail is meant to be eaten). Or Joe Yonan‘s Grilled Kimcheese from Eat Your Vegetables.

So I started to think about those recipes that I prepare year after year — along with the ones that I’ve only started to make recently out of this season’s new books — and realized that, at the end of the day, there are only a handful of them that I turn to again and again. Some of them come from books that are older, some that are newer, some that are out of print, and some that are sleepers that need to be rediscovered, perhaps this holiday season.

1. Double duck breast, from David Tanis’s A Platter of Figs and Other Recipes: An extraordinarily simple-yet-stunning way to prepare boneless duck breasts involving tying two boneless breasts together, flesh to flesh, and massaging them with a dry rub mash-up of salt, peppercorns, allspice berries, cloves, bay leaves, and garlic. We made the lovely discovery that if you leave the breasts in the fridge longer than the suggested overnight, you wind up with duck that’s just this side of cured. Better still: all that residual duck fat to strain and store in your fridge till the end of time.

2. Bo La Lot (Grilled Leaf-Wrapped Beef Kebabs), from Nancie McDermott’s Quick & Easy Vietnamese: Imagine a stuffed grape leaf filled with lemongrass-laden, garlicky ground beef that’s been marinated in fish sauce, skewered and tossed on a hot grill (or in a grill pan) and cooked until crisp; you bite into it and surprise — you experience an embarrassing explosion of Vietnamese flavor, and sinfully fragrant juices that cascade down your chin and onto your shirt. It is impossible not to make a pig out of yourself with these lovely bundles, unless you’re a vegetarian. Fabulous for pre-dinner party nibbles; you can probably make them ahead and then freeze them.

3. Boeuf Bourguignon, from The Flavor of France, by Narcissa G. and Narcisse Chamberlain. An ancient recipe that comes from an ancient book (1960), this came to me by way of my best friend from college, whose mother turned her on to it years earlier. This is about as traditional a Boeuf Bourguignon as it gets: tender meat is cooked in a cocotte with the addition of a veal knuckle (or an oxtail if you can’t find a veal knuckle) and a bucklet-load of red wine winds up blanketed in a thick, velvety sauce that you’ll want to lap up in public. A few Christmases ago, Stevie — whose now-stained-beyond-recognition xerox copy of the recipe I’ve used for almost twenty years — managed to dig up an actual hardcover of the book, which I treasure. Recipes are simple, unfettered, and extraordinary. And yes, Narcissa and Narcisse were mother and daughter, who were wife and daughter of Samuel Chamberlain, who wrote Clementine in the Kitchen. Crazy to think about someone named Narcissa naming her daughter Narcisse, but she did.

4. Roast Chicken, from The Art of Simple Food, by Alice Waters. I grew up in a home that seriously valued a good roast chicken; my grandmother made one almost every Friday night for us, when she wasn’t making brisket. She slaved over it, rubbed it with paprika, basted it, caressed it, prayed over it, threw sliced potatoes into the pan to roast around it. For hours. And it was very (very) good, but of a type. It was only when I had a poulet roti in France back in the 80s that I finally tasted what a roast chicken really can be: tender flesh, crispy skin, herby, wonderful. And this recipe from Team Waters yields exactly that. Tuck herbs under the skin, salt the bird and let it sit uncovered in the fridge for 24 hours, and roast it in a hot cast iron pan 20 minutes on its breast, 20 on its back, 20 on its breast. Let it rest for a while before serving. We literally dream about this bird in our home, and wouldn’t think of roasting a chicken any other way.

5. Goan Shrimp Curry, from American Masala, by Suvir Saran. For a long time, the idea of making Indian food from scratch in my own kitchen terrorized me; the spices, the heat, the sputtering mustard seeds (which, when they hit a hot pan, can put an eye out). This recipe changed all that; simple, rich, mouth-warming and redolent of curry leaf, tomato, and coconut milk, it’s lovely served with some steamed basmati rice and any of the dals that appear in the same book. It’s been the jumping-off point for my being fearless when it comes to preparing Indian food.

6. Grilled Kimcheese, from Eat Your Vegetables, by Joe Yonan. I thought, for sure, that I knew all there was to know about grilled cheese; when I was writing my book and I’d look at the clock and it was 3 pm and I hadn’t had breakfast or lunch (and I was ready to chew my own arm off), that’s what I would make, every time. Eventually, I learned the melting properties of every cheese imaginable, from Stilton to Wensleydale to Taleggio and Epoisses (which, when it hits heat, emits a Durian-like fragrance that makes the dog choke. I still love it.). This recipe by Washington Post food editor and all-around super-nice guy Joe Yonan combines the crunch and heat of kimchee with the creaminess of the cheese, the warm crackle of grilled bread, and a slice of sweet, Asian pear that gets tucked into the mix. When at my desk and I suddenly crave spice/sweet/salt/creamy, this is what I make (on GF bread). Again and again.

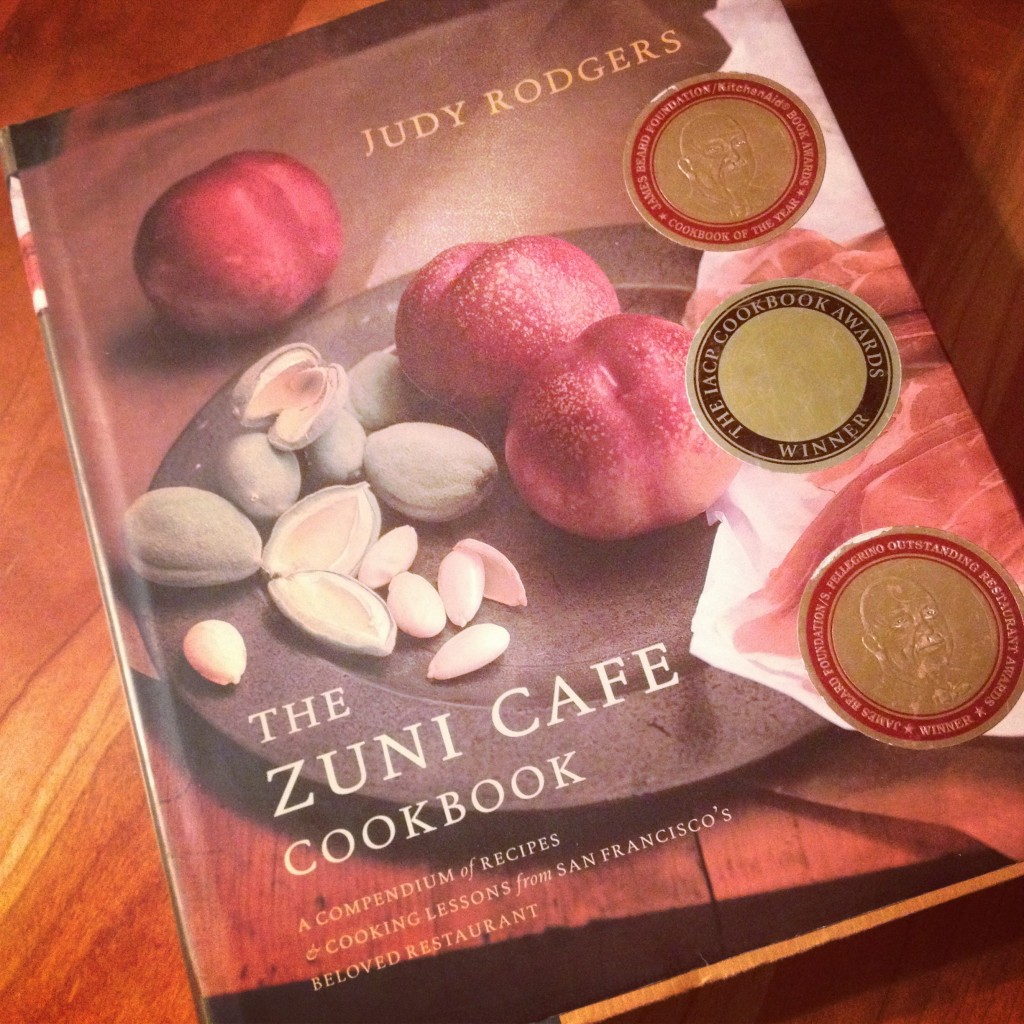

7. Miroton, from The Zuni Cafe Cookbook, by Judy Rodgers. One of the only reasons I ever make pot-au-feu is so that a few days later I can make miroton, which is a sort of layered amalgam of onions cooked down to a sweet, jammy, caramelized goo, tomatoes, and leftover, sliced beef. It all goes into a shallow gratin which is then topped with bread crumbs and olive oil, and baked until the top goes nice and crispy and the meat, tomatoes, and onion soften to a delicate, savory squish. Judy Rodgers, who the world lost just a few weeks ago, was a master at turning simple food into something utterly gorgeous and memorable, and if you need a practical starting point in her cookbook, this might be it.

8. Flageolet Gratin, from Chez Panisse Cooking, by Paul Bertolli and Alice Waters. I used to have a thing about cassoulet, that often-fetishized paean to French farmhouse food; one year, I got carried away and made my own confit and two different kinds of sausage for it. Susan and I each ate a helping, wrapped the rest of it up and stuck it in the freezer, where it sat until the following Christmas. It was delicious but over the top in richness and fat, so much so that when I took that first spoonful — after I stopped swooning — I thought I might expire on the spot. This gratin was the answer to my prayers, and I’ve made it scores of times; it calls for the addition of a prosciutto hock to be cooked with the beans, but I usually omit that with no ill effect. The resulting gratin is rich and creamy — buy the best beans you can find; I get mine from Rancho Gordo — and blanketed under a crispy, toasted breadcrumb top. Hot or room temperature, it’s lovely.

9. Sour Cherry Tart with Black Pepper Crust, from Great Pies and Tarts, by Carole Walter. I am not now nor have I ever been a baker, nor do I have a sweet tooth. But during the early summer, Susan will sometimes come home from the farmer’s market with a motherlode of sour cherries, and she’ll make this tart, which has spoiled me for all others. The counterintuitive addition of the black pepper to the crust results in a warm heat and earthiness that provides the perfect low counterpoint to the fruit. Susan has made this crust for everything from fruit empanadas to galettes, all with success. It’s utterly delicious and freezes beautifully.

10. Black bean soup from The Savory Way, by Deborah Madison. It’s freezing out, you have people coming over, some are vegetarian and some aren’t, and you want something smokey and filling, delicious and very easy to prepare; make this. I can’t count the number of times I’ve served this extraordinary soup, and each time, it amazes me all over again. There are tons of other Deborah Madison recipes that should be on this list too: tofu salad from The Greens Cookbook, rye bread from Vegetarian Cooking for Everyone, any cruciferous vegetable drenched in Deborah’s mustard butter from the same.

There are so many other incredible dishes that could and should be on this list: Shauna James Ahern‘s cornbread; Molly Wizenberg‘s Hearts and Minds cake; Heidi Swanson‘s tomato lentil soup with saffron yogurt; Edna Lewis’s fried chicken from The Taste of Country Cooking; Lucas Hollweg’s aforementioned bean soup with cabbage and bacon from Good Things to Eat; Viana La Place’s green olive and lemon relish from The Unplugged Kitchen. For now, I’m settling in with the best new cookbooks of the season — my favorites of the year, below — with the expectation that my list of beloved recipes will just continue to grow and grow, as will my piles and piles.

There are worse things.