In 2004, Susan and I had just left Harwinton — a small town of 3,500 in rural northern Connecticut — after living there for three years. We first met in the chilly autumn months of 1999, began seeing each other in January of 2000, and moved in together almost a year later, after twelve months of long weekends and weepy Monday morning goodbyes. This was it for me; I knew it was, pretty quickly. And leaving Manhattan — where I was born and raised and where I returned after college — for love was something that didn’t need a whole lot of mulling-over. Some of my friends thought I was out of my mind; my mother didn’t take it well. But love is love, and when I closed the door to my East 57th Street apartment behind me, I could only look, and move, forward. It’s the right thing, my father said to me. It’s love, and love is love.

In 2004, Susan and I had just left Harwinton — a small town of 3,500 in rural northern Connecticut — after living there for three years. We first met in the chilly autumn months of 1999, began seeing each other in January of 2000, and moved in together almost a year later, after twelve months of long weekends and weepy Monday morning goodbyes. This was it for me; I knew it was, pretty quickly. And leaving Manhattan — where I was born and raised and where I returned after college — for love was something that didn’t need a whole lot of mulling-over. Some of my friends thought I was out of my mind; my mother didn’t take it well. But love is love, and when I closed the door to my East 57th Street apartment behind me, I could only look, and move, forward. It’s the right thing, my father said to me. It’s love, and love is love.

Two years after I left New York, on a murky Sunday wet with humidity, my father and his longtime companion were in a car accident that was ultimately fatal for him. I was grief-stricken — am grief-stricken, even now; grief has no time limits or cut-offs, despite the earnest nudgings of well-meaning family members to move forward, to get on with things — and I turned to writing as a way to breathe again. It was all I could do; that, and build my new life together in another state, with my love. Eventually, after three years in a charming small town that had just gotten its first stoplight in 1996, we decided to move closer to New York; Susan had begun working at Random House and couldn’t make the commute from so far away. I was writing for anyone who would let me: newspapers, magazines, websites. I worked as a ghostwriter, a travel writer, a political writer, a restaurant reviewer, a cookbook writer.

You should try food blogging, one of my friends said. There’s this woman out in Seattle who just started doing it.

I looked at her blog; I was instantly captivated by her sense of fun, her bravery, her way of writing about food that was utterly immediate and elemental. I loved her honesty and kindness. She too, I learned, had recently lost her father, and had turned to blogging as a way through her grief. And, in the scores of readers like me who waited for her next post to go up so that I/we would be compelled to cook something that I/we ordinarily wouldn’t (a flan; an egg and tomato gratin; a walnut cake) was a guy — a curly-haired musician who lived on the other side of the country. They found each other on line, as it were, in the way that Susan and I had, years earlier. Mostly.  Molly Wizenberg and I met, eventually, when we were both speakers at the Professional Food Writer’s Symposium at the Greenbrier. At this point, I was already a dedicated reader of Orangette, and when we said hello I turned into a yammering, stammering, blithering idiot; she was gracious and kind, and a little shy, and she smiled a lot. I thought about her name, Wizenberg—probably, I guessed, from the German, Weisen-berg — and that it translates to mountains of wise men. I read her first book, A Homemade Life. And then I read it again and again, over and over, crying like a damned fool every time. And then laughing, and smiling. And cooking. This, I realized, was life: crying and laughing and smiling. And cooking.

Molly Wizenberg and I met, eventually, when we were both speakers at the Professional Food Writer’s Symposium at the Greenbrier. At this point, I was already a dedicated reader of Orangette, and when we said hello I turned into a yammering, stammering, blithering idiot; she was gracious and kind, and a little shy, and she smiled a lot. I thought about her name, Wizenberg—probably, I guessed, from the German, Weisen-berg — and that it translates to mountains of wise men. I read her first book, A Homemade Life. And then I read it again and again, over and over, crying like a damned fool every time. And then laughing, and smiling. And cooking. This, I realized, was life: crying and laughing and smiling. And cooking.

When my late mother-in-law and I were at one of the lowest points in our relationship I baked her Molly’s Hearts and Minds Cake. There was nothing else to do; it saved us, and we moved forward.

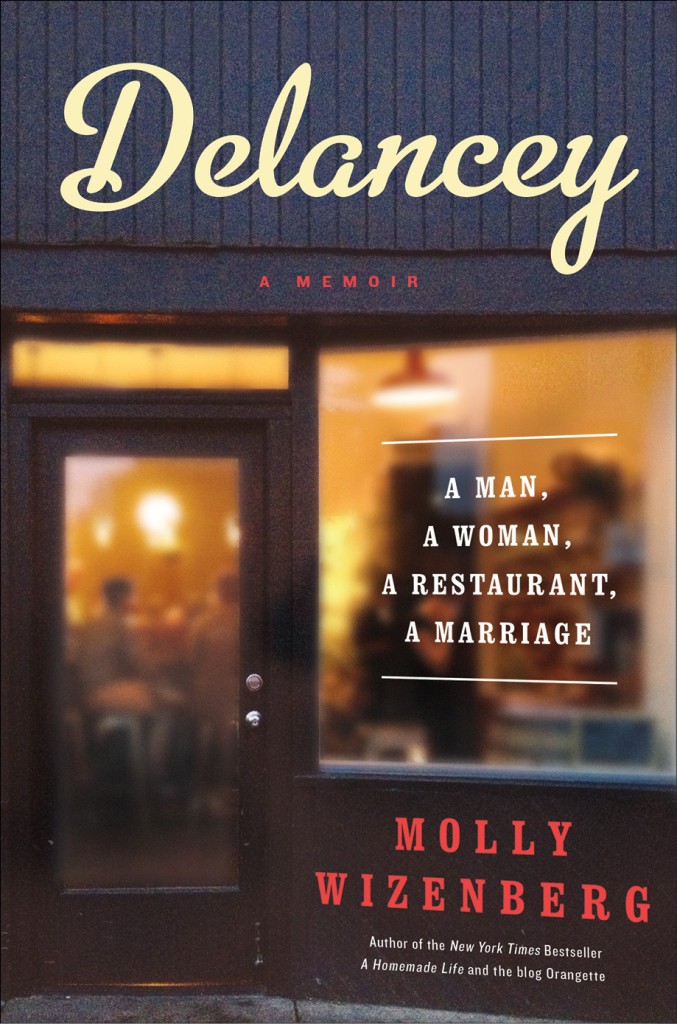

Molly’s story is now well-known; she blogged brilliantly, long before blogging was a household word. She met a lovely, kind man, and he left the east coast for Seattle, and they married. But I don’t think anyone would have predicted that, all these years later, she and Brandon would have opened up a pizza restaurant that they were going to call Delancey. I remember her telling me about it in its earliest days.

A pizza restaurant, I thought. How nice.

I’m from New York — Manhattan by way of Forest Hills, where I grew up with the best pizza in the city literally across the street from my apartment — and so when Molly told me about this place that she and Brandon were opening, I smiled and quietly wondered what the hell they were getting themselves into.

Opening up a restaurant, like love, is a romantic notion, until you do it; instead of cranky exes hovering in the wings waiting to pounce, you have to deal with permits and ovens and tiling and payroll systems and dishwashers and sous chefs and front of house and food deliveries and the one enigmatic character who invariably shows up in the kitchen and turns it, literally, upside down. The act of opening up a restaurant is like giving birth to a baby with an anger management problem; you never know when it’s going to rage, or coo, or rip off its diaper and hurl it at an unsuspecting passer-by. With luck, the end product is so gorgeous, so delicious — so stunning — that the crazy process grows misty and faint, and all you can do is look back at it and know that every drop of sweat and blood that went into it made it what it is.

One weekend shortly after Delancey opened, I flew out to Seattle and Molly fed me Brandon’s pizza and I stopped rolling my eyes. I stopped talking. Here was this man — not a trained chef — who, together, with his wife and against all possible odds, created the best pizza I had ever tasted; his process was honest and pure, his ingredients were honest and pure, and he sourced them as though they were worth their weight in gold.

To this day, it is the finest pizza I have ever tasted anywhere — including New York — produced with focus and attention and a level of integrity that, in a world crawling with poseurs, is hard to find. Sitting at the front counter at Delancey next to Molly, with Brandon in the kitchen sliding gorgeous pies into a blazingly-hot oven, I looked around on my first visit and realized that this was it; this was Molly and Brandon in their life together, moving forward, stepping into their next phase as a couple and a part of their community, in love with the food and the process and everything they had built together. Delancey was their pre-June baby — with all its ups and downs and twists and turns.

It was the right thing, like my father had once told me; love is love.

I was deeply honored to read Delancey-the-book in its earliest inception; Molly’s newest memoir, and the story of the birth of the restaurant during the freshest days of her life together with Brandon is not only the tale of one couple building a dream. It’s the story of building a dream when you don’t even know that that dream is, in fact, your dream; it’s about risk-taking and trust and what it means to put one foot in front of the other and walk through the next stage of your life with the person you adore.

Back in 2004, swimming through a sea of grief, looking for a toehold and something to hang on to that was fast and true in the face of the unknown, I found Molly’s work; her writing, her story, and her food steadied me then, and I still turn to it now when I’m out there, flailing around, unsure of what’s real and what isn’t. Delancey is the delicious tale of Molly’s next chapter; my copy, dog-eared and already falling apart, is a joy to read and re-read.

Thanks Molly, for sharing your world with us. x