All over my office: pictures.

Stacks, everywhere.

On a cold night in 2017, I carried out of my mother’s apartment an old brown and gold vinyl club bag — the kind one might bring to the gym in 1976 — filled with curling photos, papers, report cards, publicity clippings (hers), letters home from camp (mine). I don’t know when she had done this — methodically stuffed the bag full of the detritus of our life — but she had, and when it could hold nothing else, she zipped it closed and shoved it into the back of the closet in the den where after college graduation I had slept on a bad pullout sofa for two years until my doctor, alarmed by my blood pressure and the regularity of my burst ocular blood vessels, wrote me a prescription that said MOVE OUT.

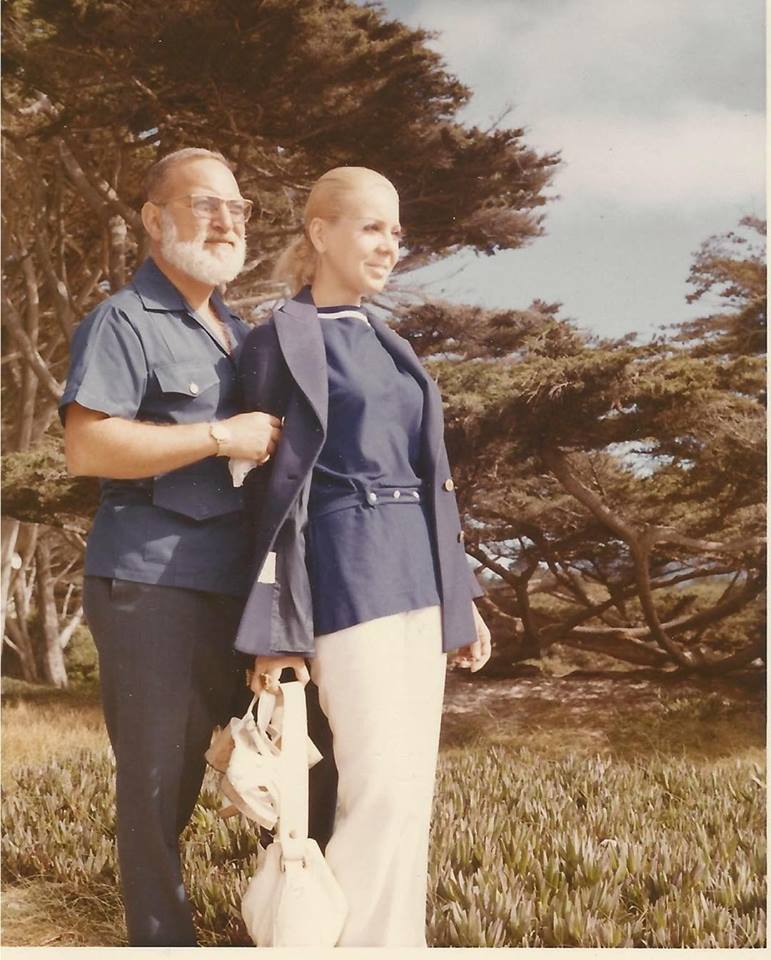

The bag had become a filing cabinet of sorts, and over the last few years, I spent hours and days pouring over its contents, trying to create some kind of order: photos from the sixties and seventies in one pile, crayon drawings in another, letters back and forth in another. I was trying to make sense of us through a taxonomy of our lives, mother and daughter, middle class, comfortable: the former, a professional television singer and model, so glamorous she nearly shimmered, addicted to makeup, suffering from Narcissistic Personality Disorder. The latter, different, reserved, the opposite in every manner of the woman who bore and raised her. The images were familiar: mother and daughter posed on the marble steps at Caesar’s Palace in 1970. The mother poured into a slender black sheath on a Saturday night in 1965. Mother and father amidst the scrub pine in Big Sur, in a stunning photo taken by their seven-year-old daughter with her father’s heavy medium format camera. 1970.

Here, he said: Point the camera, and squeeze the trigger.

In 1974, the pictures suddenly stop.

The letters back and forth stop.

The drawings and the postcards stop.

What happened to us?

What had I been looking for in the bag? What story was I trying to piece together? When did my life with my mother — my beautiful, tempestuous, addicted mother — begin to shred into pieces? Attempting to apply order to chaos is what storytellers do; it is why we are here. To make sense of the narrative of our lives and the lives of others. When my mother suffered a catastrophic fall in 2016 that required my return to her side — I had fled our codependent life nearly twenty years earlier — the roles reversed. With my mother, now in her eighties, and me faced with being her caregiver after more than half a century of enmity and fury, I wanted to understand exactly who we were. How we got to this place.

I wanted to know whether or not healing would ever be possible.

With more than 43 million Americans, most of them women, now in the role of inadvertent caregiver to a parent — half of those parents are mothers — a vast number of us are stumbling around in the dark, not only finding our way through the morass of caregiving bureaucracy for which there exists no instruction book and even less money, but also faced with the unthinkable yet karmically inevitable: taking care of an older parent with whom our relationship has been, as they say, complicated.

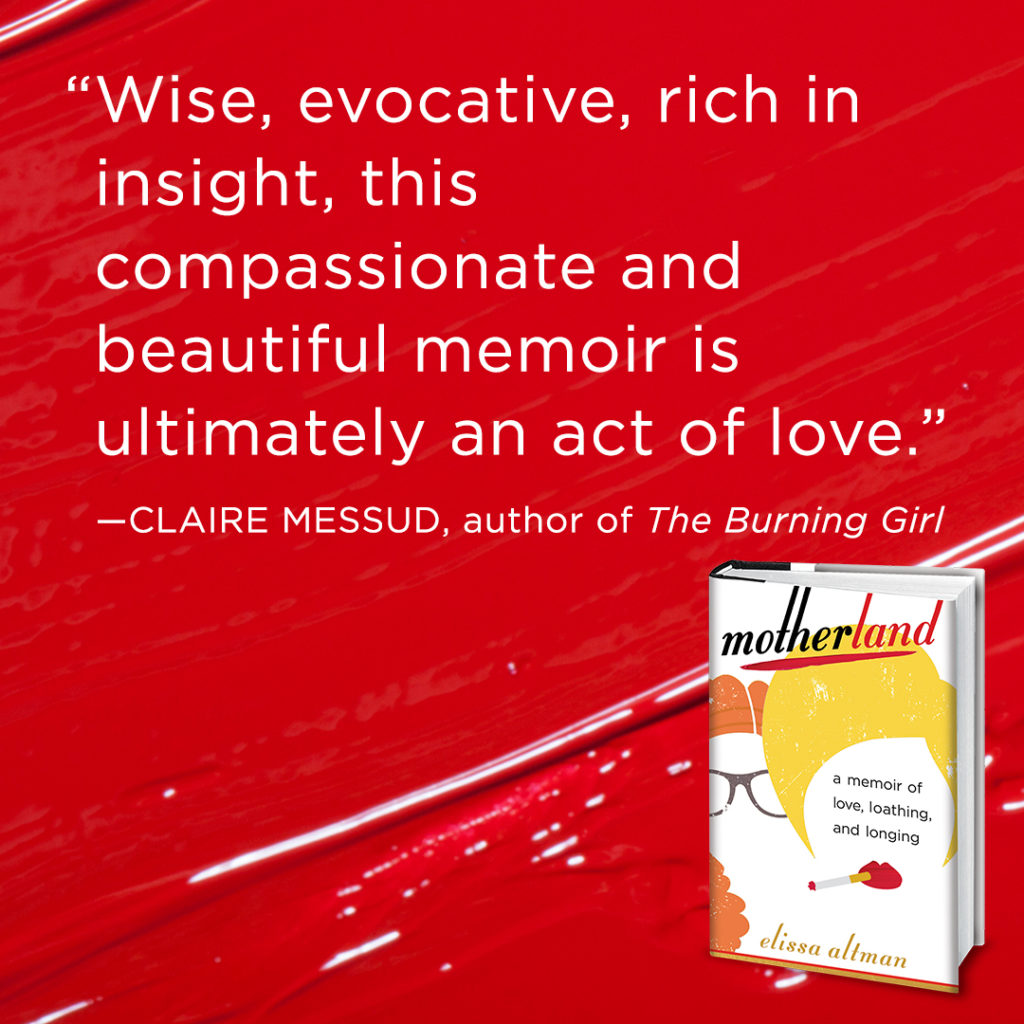

Motherland is my story and also the story of millions: the universal mother/daughter conundrum that defines who we are as women, as daughters, as mothers.

Motherland: A Memoir of Love, Loathing, and Longing, is now available for preorder wherever you buy your books: