This is what I know:

This is what I know:

The warm, spice-crusted pastrami on thin-sliced rye from Ben’s Best Deli, a few blocks from my childhood apartment in Forest Hills.

The tiny black handgun that my father kept buried under his Bar Mitzvah tefillin in the top drawer of his highboy dresser. We grew up together — the pastrami, the gun, and I; my father introduced us the same day.

*

After my mother had gone into the city to have her hair done at Vidal Sassoon, my father took me out for an illicit sandwich at Ben’s Deli, which was right next door to The Ballet Academy. It was there where I, at age three, had bald-faced lied to my teacher — a broad-hipped thirty-something dancer named Miss Carolyne — and told her that I’d forgotten to kiss my mother goodbye at the start of my class. I excused myself, packed up my tutu, and found my mother standing out on Queens Boulevard having a cigarette in front of Ben’s. Each time the door opened, the smell of pickle brine and schmaltz wafted out and engulfed us. I handed my mother my pink patent leather ballet tote, and told her I quit.

The afternoon of my mother’s haircut — four years after I abandoned my chance to be a ballerina — my father ordered pastrami sandwiches for both of us and they arrived unadorned, on two small white Buffalo china plates. There was no fanfare or accoutrement; just seeded bread and dark red meat edged with ripples of lace-white fat. Half-sour pickles bobbed like apples in small metal vats on each table, next to cups of yellow mustard and the can of Dr. Brown’s Cel-Ray soda we shared. Up to that point, I had never eaten pastrami because, for one thing, my mother hated it. For another, it had long been considered adult food in my family; it was a little bit hot, a little bit greasy, and therefore, a little bit dangerous. Instead, I had been relegated to milder meat, like tongue. But when I tasted the pastrami that afternoon for the first time, I loved the salt and the smoke and the brine, and the way the blackened ends of the meat, pungent and crisp, were softened by the caraway in the bread.

We ate in silence; my father seemed preoccupied. When our sandwiches were done, we left and walked hand-in-hand the three blocks to our apartment, until I let go and skipped down 67th Avenue ahead of him, past the tiny Orthodox synagogue and the back entrance to our pool club stinking of chlorine, and the old people’s sitting park where I’d learned to walk, right after we moved in in 1964.  There’s something I want to show you, my father said solemnly, while we were standing alone in the elevator, on our way up to the eighth floor.

There’s something I want to show you, my father said solemnly, while we were standing alone in the elevator, on our way up to the eighth floor.

When he opened our door, he patted our dog on the head, and I followed him past the kitchen and into the bedroom he shared with my mother. We stood together in front of his tall dresser, facing their new, fourteen inch Zenith television.

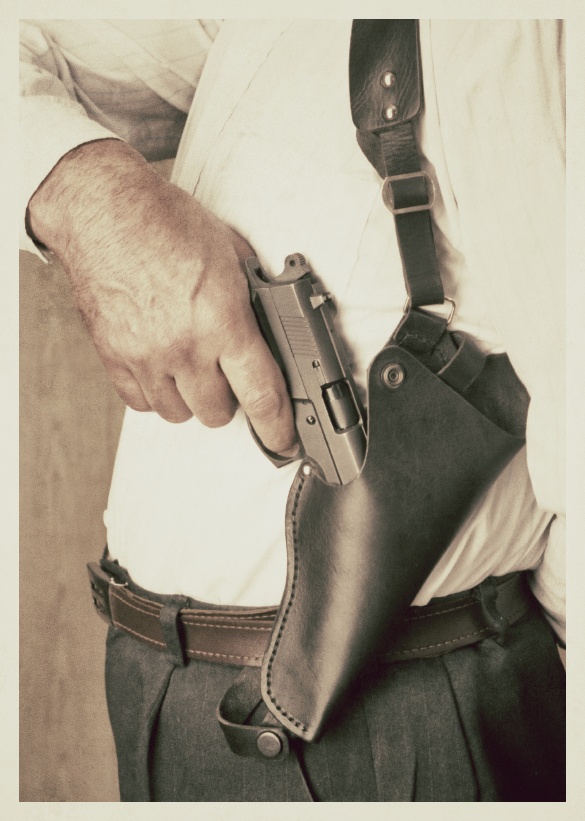

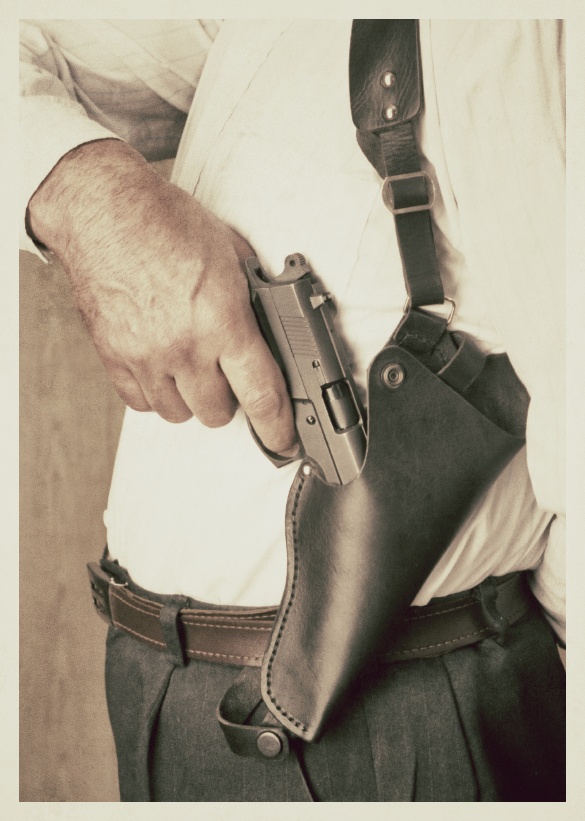

He slowly pulled open the top drawer, took out his phylactery, and tossed the jumble of cracked leather straps and wooden blocks onto the bed. Underneath it was a shiny brown cordovan arm holster, shaped like a triangle; he lifted it out of the drawer like a stillborn baby and unsnapped the top flap. Inside was a small black handgun with a black trigger.  I never want you to touch this; I want you to know that it’s here, but you can’t ever touch it. Not without me holding it.

I never want you to touch this; I want you to know that it’s here, but you can’t ever touch it. Not without me holding it.

Is it real? I whispered, looking up at him.

My parents had just taken me to see The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly, and even at the age of seven, I understood the possibility of guns.

It shoots tear gas, he said, almost apologetically.

My father let me hold it; I cradled it, and instantly turned it around and looked down the barrel, to try and determine whether it was the sort of gun that shot bullets, or, as my father claimed — perhaps to protect me — shot tear gas; it felt heavy and solid and gorgeously weighted, like the western, pearl-handled six-shooter cigarette lighter that my father’s friend, Bill, had sitting on his coffee table. When I gave it back to him, my father snapped it back into the holster, slipped it over his shoulder and fixed the belt around his ribcage, like Gene Hackman in The French Connection. We looked in the mirror, standing side by side. He patted it, took it off, put it back in the drawer, and covered it back up with the blocks and straps of his tefillin.  For the years that followed that afternoon of forbidden guns and deli, I touched that pistol almost every day, because that is what children do. If you entice them by introducing a proscribed object to their lives and you tell them not to go near it, they will go near it. They will eat the pastrami; they will play with the gun. Nearly every afternoon, if I was alone in the apartment — and even if I wasn’t; my grandmother essentially lived with us — I’d skulk into my parents’ empty bedroom, open his dresser drawer, shove his tefillin to the side, and take out his pistol. And every time I did that, I would look down the barrel of the gun and stare, wondering whether or not it was real.

For the years that followed that afternoon of forbidden guns and deli, I touched that pistol almost every day, because that is what children do. If you entice them by introducing a proscribed object to their lives and you tell them not to go near it, they will go near it. They will eat the pastrami; they will play with the gun. Nearly every afternoon, if I was alone in the apartment — and even if I wasn’t; my grandmother essentially lived with us — I’d skulk into my parents’ empty bedroom, open his dresser drawer, shove his tefillin to the side, and take out his pistol. And every time I did that, I would look down the barrel of the gun and stare, wondering whether or not it was real.

The year before he moved out, my father started wearing his piece when he took the dog out after dinner; it was why he bought it in the first place, all those years before, he told me. By that point, I was fourteen, and the idea of my diminutive, Chopin-loving father packing heat was peculiar. Still, he was able to somehow justify it: it was 1977, Son of Sam was terrorizing our neighborhood, and he felt safer with it as he walked the dog to Queens Boulevard to get himself a felonious post-supper pastrami sandwich at Ben’s, without my mother knowing about it.

Do you really think that shooting tear gas at someone will make you safe? I asked him one night, sitting on his bed while he slipped his arm through the shoulder holster. My mother was out with clients, and had no idea that her husband had somehow turned into Clint Eastwood with the passing of the years.

He snorted and changed the subject.

Do you want a sandwich? he asked, turning around to glare at me.

An hour later, he appeared in my bedroom doorway with a brown paper bag stained with grease, stinking of forbidden pastrami brine and the half sour pickle that always accompanied it. The next day, before he and my mother got home from work, I put my schoolbag down on a chair in the living room, went into their bedroom, opened the drawer, took out the gun, looked down the barrel, and wondered what I had since I was seven: whether it was real.

That summer, I lay on my belly at the rifle range at sleep-away camp; eight of us were propped up on our elbows, listening to an unsmiling counselor hand down the rules: no shooting until he gave us the signal. Everyone got one bullet each. We were to unlock, load, aim, and when he said to, fire. And no one was allowed to get their target until everyone had finished shooting.

My mind was elsewhere that July: I knew that my parents’ separation was imminent. I wondered where I would live, what school I would go to, what would happen to the dog, and if I’d wind up on the stand, crying in front of a judge who would make me implicate one parent over the other, like in the movies. I mindlessly loaded, aimed, and fired, and the counselor screamed.

What the hell are you doing? You could kill someone if you don’t pay attention to me.

I’m sorry–I said. I wasn’t thinking. And I wasn’t.

My throat tightened as the rest of the kids on the line called me an idiot, and the unsmiling riflery counselor grabbed the rifle out of my hands by the barrel and walked out to pull my target off its wooden backdrop. Instead of the target, he came back carrying a small, still, white bunny, a bright red splotch no bigger than an eraser head right between its pink eyes. You did this, the counselor said, as I stood up and ran back to my bunk, sobbing. I lay on my bed, crying, until the dinner bell rang. At the end of the camp session that year, in August, I was awarded a riflery badge for expert marksmanship; my grandmother wanted to sew it onto the navy blue, woolen CPO shirt my dad had gotten for me at the local army navy. I wouldn’t let her, and used my father’s plastic Bic lighter to incinerate it in our bathroom sink, where I could extinguish it before anyone knew.

That fall, right after school started, the man who owned the pizzeria across the street from my building was murdered one night, shot at point blank range as he walked the block from the shop to his apartment, four flights below ours. For weeks after, we would see his widow, a pale, red-haired woman, wandering our neighborhood in a daze until someone would bring her home. In early September, right before my parents separated, my father came downstairs one morning to the garage beneath our building, to find a small bullet hole in the driver’s side window of his Buick Electra. It went unreported and unresolved and, until he sold the car a few years later, unmended; my father said that it was a constant reminder of the fragility of life.

Before he moved out in 1978, my father up packed everything that meant something to him: his jazz records and his stereo, his cameras and his Navy flight charts, his Yiddish typewriter, his Philip Roth and his Henry Miller. He took me back to Ben’s for lunch; we ate pastrami sandwiches and half sour pickles and cans of Cel-Ray soda. My mother was at work, and after he dropped me off and drove away, I went into what had once been the bedroom he shared with her, and opened the top drawer of his empty dresser. The pistol was gone; all that was left was his tefillin and an ancient, dog-earred book of matches from Ben’s, stained with a telltale fingerprint of yellow deli mustard.