It’s been a while since I’ve posted here, but I have a reasonably good excuse: I’m (very) deep in the throes of writing my next book, which is slated for publication in the Fall of 2015. I won’t/can’t talk too much about it for reasons mired in everything from superstition to the unspoken rules of the road, but I will say this: my office presently looks like the Collyer Brothers live here. There are piles of stuff everywhere. I’ve managed to unearth pictures of my childhood home from an on-line Columbia University Real Estate Brochures collection, and I’ve taped it up next to my desk; every time I look over at it I end up feeling like I’m in the front seat of a roller coaster, climbing to the peak, itchy with that familiar combination of mild terror, who-the-hell-conned-me-into-doing-this fury, OFF OFF GET ME OFF hysteria, and weak-kneed curiosity. I can’t look away, but when I do, I get to work.

As my beloved spouse has discovered, I tend to fall into certain patterns when I’m working on a book: I’ve learned that I’m most productive in the afternoon. The morning’s phone calls have been made, emails have been sent, editing has been done, articles have been written, I’ve read the New York Times, scanned (and spent too much time on) Facebook, walked the dogs and fed them, fed the cats, gone to the gym across town, gone to the grocery store or CSA or farmer’s market, come home, and after showering, I manage to get my ass in my chair. At which point, assuming I got up early, it’s probably noonish, which means I have roughly eight hours to write until Susan comes home, exhausted and spent, after a five hour round trip commute to a job she loves in Manhattan.

It used to be that I’d get so carried away with the writing — so totally sucked in — that I’d look up and it’d be 7:30 and I could hear Susan’s car pull into the driveway. I wouldn’t have noticed it getting darker outside, I wouldn’t have looked at the clock on my computer, and then suddenly I’d have an OH SHIT moment — what had I made for dinner? (This is the way we do things here: if Susan is going to haul herself out of bed at 5 am in order to make a 6 am train in order to get to Manhattan by 8:30 am, then work all day, then race back to the station to get the 5:50 which will have her walking through the door at nearly 8 pm, it is my job and responsibility to feed her, and feed her well. It is my job and responsibility to make sure that dinner is on the stove, waiting for her, and that all that’s left for me to do while she sits in a chair in the kitchen, sipping a glass of wine, is stir the pot. And I don’t mean that metaphysically.)

All of which is to say that I’ve slipped into small-bowl-mode; when I’m writing a new book, weeknight dinners are very often anything that can served in a single, small bowl. They don’t have to be vegetarian, or vegan, or they might be. They might be something as simple as a bowl of vegetable soup, or pork-and-vegetable fried rice topped with a poached egg gifted to me from my neighbor, Melissa, who is very gifty when it comes to her chickens (we’re very lucky around here, egg-and-neighbor-wise). It could be a pile of spinach, wilted to a tangle and tossed with garlic and hot red pepper flakes, or pasta, or Hatch chile posole.

if you step into my kitchen, one of the first things you’ll see is an immense, battered glass-doored cupboard that Susan and I bought about eight years ago at a furniture consignment shop not too far from where we live; it’s vaguely white, and as the chipped milk paint shows, was once forest green. One of my cousins asked me when we were going to refinish it, but we’re not; we love its aged-ness. It took the delivery guys two trips to get it here — so huge were the two pieces that there was no way we could get it here in our car — but once set up, it became the center of our kitchen, and the repository for a ridiculous number of platters (lots of ironstone, lots of old Pillyvuyt, a beloved antique turkey platter that came down to us from Susan’s Aunt Millie). It holds the heavy result of my mortar and pestle addiction. But more than anything else, it is home to dozens of small bowls: coffee bowls, old Bennington white-on-white bowls that I bought years ago when I still lived in Manhattan, Asian bowls, cream-colored cereal bowls that we bought at a Goodwill in Middlebury, Vermont, only to discover that they were handmade by a relatively famous potter in the mountains of North Carolina. There’s Susan’s grandmother’s favorite cereal bowl, a stack of Duralex Picardie glass bowls, and footed/earred Pillyvuyt bowls that are perfect for making onion soup because you can pop them under the broiler without worrying about breakage.

I don’t recall when I became so bowl-crazed, but I think it was right after my pitcher fixation went on the wane; in my tiny, dark Manhattan apartment, I had dozens of them — some antique, some not — and it took me a while to realize that my pitcher addiction was ridiculous because, for one thing, I don’t actually ever put anything in my pitchers: while I love cheese, I don’t drink milk and never have. When I use cream in my kitchen, it goes directly into whatever dish I’m cooking that requires it, and is therefore acquired in small half-pint containers. So once I got the pitcher thing out of my system (which, to be totally transparent, came after the antique teapot problem), I turned my attention to platters and bowls. Both of them imply serving, but also, practical intimacy, and what’s more intimate than feeding people, and sitting down on an early autumn night with the person you love, and feeding them something soothing out of a vessel that, when held in your hands, forces you to cradle it as you would the face of a small child.

During a particularly long writing binge, I heard Susan’s car pull into the driveway and realized that I had made nothing — literally nothing — all day; I hadn’t thought about dinner, hadn’t gone out shopping in the morning, and now she was about to walk through the door, hungry, wanting to be asleep by ten, and all I had sitting in front of me in the kitchen were two cans of garbanzo beans and a lemon. And, as the old saying goes about necessity being the mother of invention and all that….

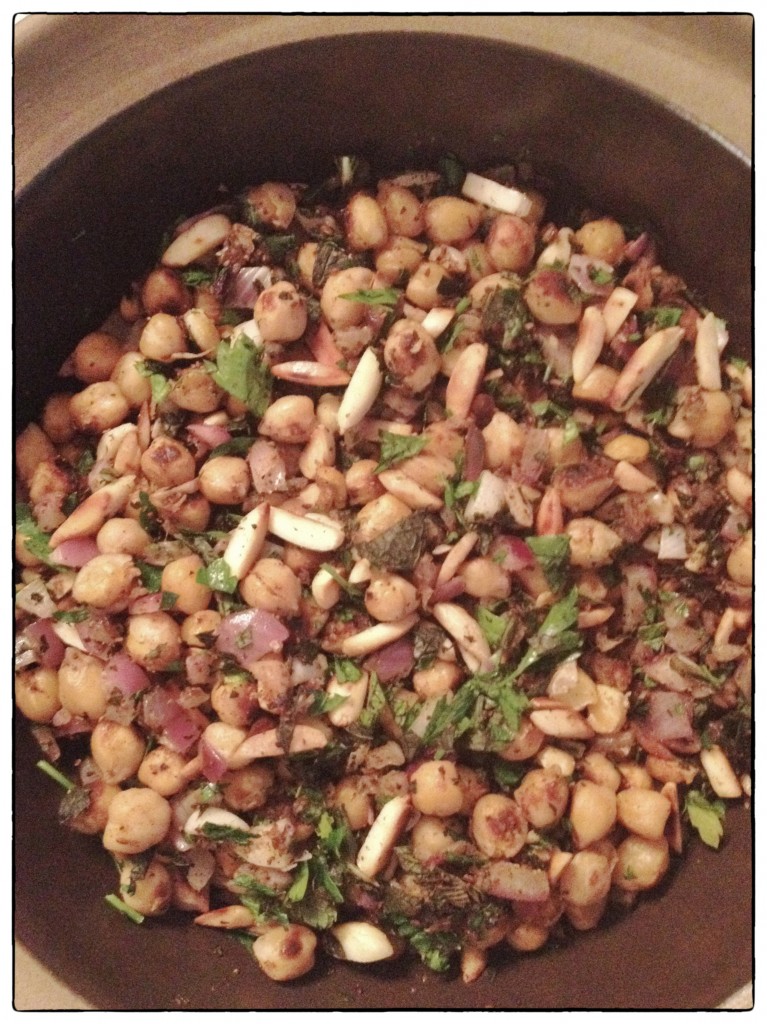

I adore garbanzo beans; I always have. But after years of eating them damp and slimy and bland out of some office cafeteria salad bar, I wondered what would happen if you toasted them. Not toasted them as you would to make them crunchy — I’ve made many batches of them spread out on cookie sheets, dribbled with olive oil and tossed around with pimenton and cumin and salt (totally addictive) — but toasted as you would nuts, so that they retain their tenderness, inside a small amount of delicate toothsomeness. I wondered if by toasting them they’d get aromatic, and nutty. And the answer was yes and yes. That night, that’s what I did, and the result — after I tossed the still-hot beans with diced red onion and garlic, dried lemon peel, cumin, toasted slivered almonds, and feta — was this salad-y kind of thing that’s savory, toothsome, bright, earthy, and so good that when I made a triple batch to take to an outdoor concert with some of our neighbors this summer, it was gone before the music started.

What made it so good, though, that first time I served it to Susan? It was one of those inventions that stuck, that required total focused attention in the kitchen. I couldn’t think about work, or writing, or deadlines the first time I made it. Instead, I had to focus on texture and flavor, and what would add brightness and what would be overkill. And whether I would incinerate the beans if I stepped away at the very moment they released all of their beany sugar and starch, and threatened to go black in the amount of time it takes to sneeze.

I’ve made this dish at least ten times this past summer, and I think that it’ll be perfect as we head into the cooler days of autumn; on a busy weeknight, it’s been the perfect thing.

But always out of a small bowl, with a glass of wine.

Toasted Garbanzo Bean Salad with Lemon Peel, Mint, Feta, and Almonds

Having made this salad approximately ten times in the last three months, I’ve learned the following: it takes a comparatively long time for the beans to expel their starch, sugar, and beany liquid, and to actually begin to toast (whether you use canned or dried beans apparently matters little; I’ve done it both ways), so patience is required. You’ll also want to do this in a relatively dry cast iron skillet: add olive oil — too much olive oil — and everything will fry, which is what you don’t want. The diced red onion added raw to the hot beans is not a mistake; the heat from the beans softens and slightly cooks the onions, but only slightly. Finally, the amount of parsley and mint in the dish seems ridiculous overkill: it’s not. Aromatically-speaking, the result is a bit like being in a souk (I say this never having been in a souk). Leave out the feta and the dish will be vegan; leave out the almonds and it will be nut-free. (But you know that.) I leave out salt (between the lemon, vinegar, and feta it hardly needs it) but if I did add it, it’d be coarse flakes, like Maldon.

Makes 6 servings

1 tablespoon cumin seeds

1/2 tablespoon coriander seeds

1/2 tablespoon extra virgin olive oil

2 14-ounce cans good quality garbanzo beans, drained, rinsed, and shaken dry in a colander

1/2 medium red onion, finely diced

2 cloves garlic, minced

1/2 cup slivered almonds

1 tablespoon dried lemon peel*

large handful mint leaves, chopped

large handful flat leaf parsley leaves, chopped

1 large lemon, zested and juiced

Extra virgin olive oil, to taste

Red wine vinegar, to taste

1/2 cup crumbled feta

In a large dry cast iron skillet set over medium heat, toast the cumin and coriander until fragrant; remove from the pan and grind in a clean coffee grinder (or smash in a mortar and pestle) and set aside.

Do not wipe out the pan; heat the half tablespoon of olive oil until it begins to ripple, and add the garbanzos to the pan. Toast them slowly, shaking the pan every few minutes: they will appear to stick to the pan, but they will ultimately release, and blister. Stir frequently with a small spatula; this should take approximately 10 minutes. If they appear to burn, lower the heat slightly.

In a small pan set over medium heat, toast the almonds until just fragrant, remove from heat, and set aside. Return the toasted cumin and coriander to the pan with the beans, and gently fold (so as to not smash the beans). Remove the pan from the heat and add the onion and garlic; stir well to combine and let rest for 5 minutes.

Fold in the toasted almonds, the lemon peel, mint and parsley. Add the lemon juice and zest, and toss well to combine. Drizzle with olive oil and red wine vinegar, and toss again.

Top with the feta, and serve warm, cold, or at room temperature.

*Find lemon peel in your local Middle Eastern grocery store.