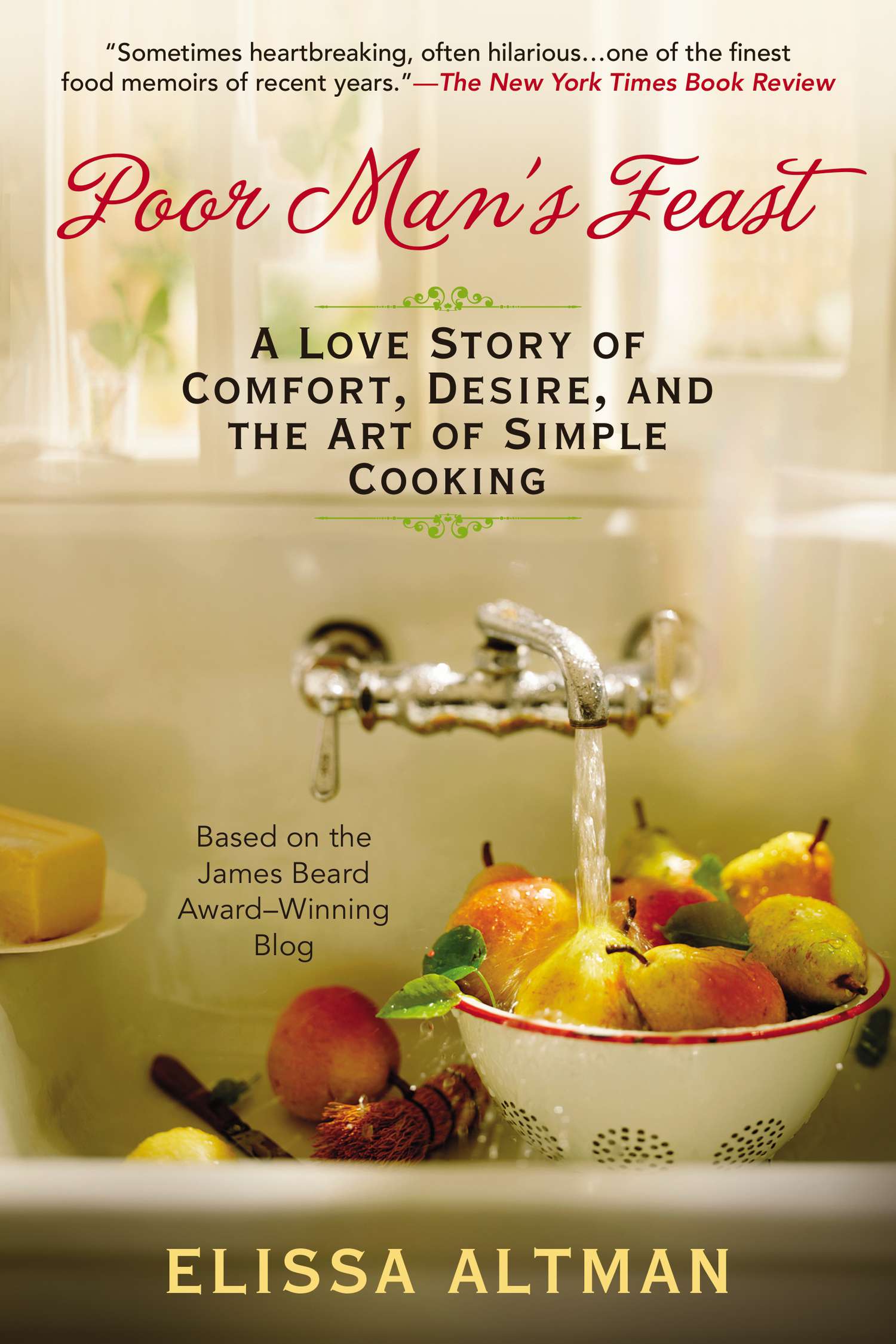

It’s been a long while since I’ve written, but I have a (semi-) decent explanation: I’m coming in to the end zone on my next book, which will be published by Berkley Books, most likely in autumn of this year. (I’m very happy to also announce that Poor Man’s Feast: A Love Story of Comfort, Desire, and the Art of Simple Cooking is coming out in paperback this August, also from Berkley, the fact of which makes me want to shriek with glee. If it weren’t so very out of character.) Here’s the gorgeous new cover, for which I’m so totally grateful to Berkley’s design team. Damn, they’re good.

I wrote Poor Man’s Feast over a period of about sixteen months, from late 2010 into very early 2012, and I’d forgotten what it’s like — the sitting down every single day, the isolation, the writing bird by f**king bird, the forgetting to have breakfast or lunch as I get Hoovered deep into the wormhole that writing memoir seems to require. When I was writing Poor Man’s Feast, I spent days reliving the early part of my new relationship and food’s role as our third, silent partner: I relived that primal urge to cook for someone during our first year together, and what it tasted like, looked like, and felt like to us in that narrow sliver of time where we managed, against all odds, to find each other and make it work. I had been a single city woman for so very long. She had ended a longtime relationship a year or so earlier and retreated to the place where she grew up, in the (very) rural Connecticut countryside. One afternoon a few months after we met, I mistook a large bear emptying the contents of the neighbors’ bird feeder into its mouth for a purebred Bouvier I was certain had just escaped from a nearby Litchfield manse after winning a local AKC competition.

That’s how it went for a while with us: all country girl/city girl.

There was, of course, a lot of food in Poor Man’s Feast: there were the illicit, fancy French meals that my father and I shared under the wire when I was a child and my mother wasn’t looking. There were the cavernous restaurants we frequented in 1970s Manhattan — Maxwell’s Plum and Mr. Chow and Sign of the Dove — which gave way to my brief stint at cooking school in the late 1980s, where I failed chocolate, and two years working at the original Dean & Deluca, where my days were filled with six-figure, brain-sized truffles from Alba. There were the obscenely tall meals I made in a pompous, fruitless attempt to woo my new partner; unmoved, she simply knocked them over like the fragile house of cards they were. There were the less-expensive butcher’s cuts I learned to prepare as we began our parsimonious life together — the shanks and the oxtails and the cheeks — that demanded I stop cooking with hysterical bursts of fire and flash and instead commit myself to slowness, focus, and care. In learning how to cook this way for Susan, I learned how to live this way, which I still mostly do, unless my mother is visiting or Mercury is in retrograde. Or both.

So with that story — a tale of how sustenance for the belly goes hand in hand with nourishment for the heart and spirit — about to appear in paperback, I find myself back at my desk and writing the next book: Treyf: A Memoir of Family, Food, and the Forbidden. I can’t/won’t talk too much about it beyond the fact that it’s about human transgression — in the kitchen, at the table, in love, even at prayer — and what happens when we use taboo — including prohibited foods — as a way to separate past from present. Pre-hipster Williamsburg, Brooklyn makes a guest appearance in Treyf (my great-grandfather, Marcus Gross, owned a kosher butcher shop within spitting distance of what is now the pork emporium, Marlow & Daughters); so does 1970s Queens, The 2000-Year-Old-Man, Peggy Lee, Spam, Devils-on-Horseback, fondue pots, and the pork dumplings and shrimp and lobster sauce served at my best friend’s Bat Mitzvah in 1974.

In addition to food and family, there also seems to be a lot of music showing up in Treyf, so here’s a short playlist just to sort of grease the contextual skids:

Meanwhile, amidst all of the writing and re-writing and editing, Susan and I just celebrated our fifteenth anniversary. We met in 2000, on a freezing January Saturday afternoon and have been together ever since, with mercifully little time apart; this year, we celebrated with dinner at home on a bitter January school night during a recent snowmageddon when the car had just about frozen to the driveway and the roads were like a luge run, leaving me gastronomically stranded. I had been to our wonderful fishmonger a day earlier for the main course, but I wanted to make something a tiny bit different for us to nibble on while I cooked us dinner. We’re not big appetizer people — there’s only two of us — but I considered my options: I could fry the three sad Castelvetrano olives that were languishing in the back of the fridge. I could roll up the thin-sliced ham I’d bought on a whim at the coop and pipe them full of low-fat cream cheese, like my grandmother would have done in 1976. Or I could head down to the dusty Metro shelves in our basement, where we keep the weird canned goods that Susan’s late mother, God bless her soul, used to send us home with in the event of nuclear disaster.

For whatever reason, I chose the third option and uncovered some Laurel Hill Artichoke Hearts (NOT the marinated sort). Susan adores artichokes in whatever form they come, but especially Carciofi alla Giudia, which there was absolutely no chance of my turning these things into. So I settled for artichoke heart fritters, dunking them whole in a traditional, egg-based batter and bread crumbs, and then shallow-frying them in a straight-sided saute pan. Eating them hot and golden as they came out of the oil reminded me of the way we used to feed each other back in the early days of our relationship, when we lived in tiny Harwinton and simply cooked whatever we could find, devoid of show or pomp, and celebrated the miraculous fact that we had found each other against all odds.

Artichoke Heart Fritters

There are a few (important) keys to making this very easy appetizer: first, if you’re using canned artichoke hearts, buy the highest quality you can find, and make sure that they’re not marinated (they should be packed in water and either lemon juice, or citric acid, and that’s it). Second: when you pop the can, rinse and then drain the hearts in a sieve and shake it well to dry them out as best you can. Otherwise, the batter will roll right off them and into the hot oil. Finally: Lest I upset any of my anti-canned food readers…I am not advocating eating canned food over fresh. But my car was frozen to the driveway and, well, you know how the Donner Party ended up.

Serves 2

1 14-ounce can best quality artichoke hearts, NOT MARINATED

sunflower or grapeseed oil

1 large egg

1 tablespoon all-purpose unbleached flour (GF if you’re GF)

1/4 cup whole milk

3/4 cup Panko breadcrumbs (GF if you’re GF)

Maldon salt

Freshly ground black pepper

Wedges of fresh lemon

Drain the artichoke hearts in a sieve, give them a quick rinse, and shake to dry the hearts as best you can. Set aside. In a large, straight-sided saute pan, slowly heat half an inch of oil over medium heat.

While the oil is heating, assemble the batter: in a small bowl, beat the egg and whisk in the flour until the mixture is thick. Pour in the milk and beat gently — the batter should be lump-free. (If it’s too thick, add a bit more milk; if it’s too thin, carefully whisk in a bit more flour. The consistency should be that of pancake batter.)

When the oil reaches a temperature of 375 degrees F and using spring-action tongs, dip one of the hearts first into the batter, allowing any excess to drip off, and then into the breadcrumbs, coating it uniformly. Carefully set the heart into the hot oil, and repeat with the rest of the hearts. Turn the first heart over after about three minutes, and follow suit with the rest. (They should be a deep golden brown, but no darker.)

Remove them to a plate draped with a paper towel, season them well with salt and pepper, and serve them immediately with fresh lemon. They won’t keep (and they won’t have the chance to).