I believe that what we become depends on what our fathers teach us at odd moments, when they aren’t trying to teach us. We are formed by little scraps of wisdom. ~Umberto Eco

I have the metal strongbox, where he kept the hatband from his days as a Naval officer, that he let me play with as a child. I have two volumes of Slipstream, the books that he edited for the Navy. I have his wings; his flight diary documenting every nighttime run he made over the course of three years; his Naval aviator diploma from Corpus Christie dated 1944; his letters home from the Pacific; his fountain pen; his dog tags; his gold flight ring that he had turned into a charm for my mother’s bracelet. I have his leather-bound looseleaf notebook that he let me use in junior high school, and his Bar Mitzvah books from 1936 inscribed A Gift From Mr. & Mrs. M. Kastoff and Family that he gave to me when I moved out of his parents’ apartment, which he kept renting even though they’d been gone for years.

I have the ties I bought for him when I was studying at Cambridge; his gold Hamilton watch on its alligator band; his black plastic aviators from 1970; his English duffel coat that he had to have tailored because his arms were short; his leather flight jacket with his squadron patch and gold wings sewn onto the breast. I have his robin’s-egg blue metal home movie screen; his Super 8 editing viewer; his cans of home movies; his bags of birthday cards he sent to his mother from the time he was a boy; his clipping of a famous wayward cousin’s obituary, which he stored in a half-gallon zip lock bag.

I have his crates of albums from the 1950s: his modern jazz, his Moiseyev, his Mohammed El-Bakkar, his Moishe Oysher, his Chopin, his Mahler, his Lenny Bruce. I have his 1962 copy of Craig Claiborne’s New York Times Cookbook; his Dione Lucas; his 1958 Arabicaware; his Carol Stupell plates; his electric carving knife; his mother’s end table.

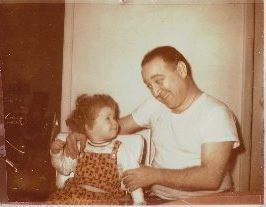

I have his picture of me just hours old; his picture of me the day of my cousin’s Bar Mitzvah; his picture of us having burgers at the Shalimar Diner in Forest Hills; his picture playing tennis with my stepmother, the love of his life. I have his picture on a horse at his dude ranch; his picture walking down the aisle at his own wedding; his picture at his ad agency. I have, sitting in my desk drawer, his brown leatherette wallet that he was carrying in his back pocket on the day of his accident; his dry-cleaning stub for clothes he would never pick up; his ticket for laundry he would never wear; his library books he would never read; his AARP membership he would never renew; his Amex card he would never use.

I have his sense of humor and his ferocious temper and his chuckle; his curly hair and his fair coloring, although not his blue eyes. I have his love of travel; dry gin Gibsons; radio storytelling; English history. I have his love of the American West; his hatred of Schoenberg; his appreciation of Danish Modern furniture, expensive German medium format cameras, good advertising, and Swiss fondue. I have his fondness for bluegrass; big dogs; San Francisco; northern New England; Iowa; Penobscot Bay; John Muir; Thoreau. I have his affection for roast pork; silvertip beef; fried chicken; remoulade; cold lobster; Schlitz; Mallomars.

I have his belief in the sanctity of cooking, and his love of feeding people.

I have his hands; his feet; his shoulders; his crooked smile; his easy teariness.

I hear his laugh; his cough; his snore; his shout. I hear him, always: over my shoulder in the kitchen; on the phone on a Sunday morning; next to me in the car; taking a practice swing while I’m teeing up.

My father’s been gone for thirteen years; he went out to run an errand, and he never came back. He lives now in my heart and my memory. In my house, I have the stuff of him, the scraps of him, but not him.

In my house, every day is Father’s Day.