A Conversation with Joan Nathan

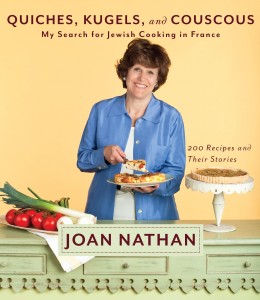

This past December, I had the honor and pleasure of speaking with one of the world’s greatest authorities on Jewish food — Joan Nathan; this remarkable author and culinary anthropologist was on tour for her most recent book, Quiches, Kugels, and Couscous: My Search for Jewish Cooking in France. As much a reading book as it is a spectacular cooking book, it pays homage to a 2,000 year old culinary culture that has not-so-quietly withstood the tests of war, anti-Semitism, time, assimilation, and cultural evolution. Today, with Passover right around the corner and Jews all over the world standing in their kitchens and cooking traditional holiday dishes that honor freedom and history, there is no better time to read this remarkable story of the perseverance of an ancient ethno-culinary mosaic, and the proud people — the French Jews — who created it.

Note: The recipe at the end of the interview is not Kosher for Passover, because of the corn starch. But believe me, it’s well worth waiting for.

I’ve loved all of your books, but your new one, QUICHES, KUGELS AND COUSCOUS, thrilled me, and made me feel deeply proud. But it also broke my heart. In writing and researching this book, you delve far into the history of Jews in France, and the recipes stand side-by-side with sometimes heartbreaking tales of courage and survival. Tell me how you came to write this book, and to focus on a subject that has been so fraught over the years, and that no one else has really touched on.

I’ve loved all of your books, but your new one, QUICHES, KUGELS AND COUSCOUS, thrilled me, and made me feel deeply proud. But it also broke my heart. In writing and researching this book, you delve far into the history of Jews in France, and the recipes stand side-by-side with sometimes heartbreaking tales of courage and survival. Tell me how you came to write this book, and to focus on a subject that has been so fraught over the years, and that no one else has really touched on.

Well, I always think—especially with Jewish food, but really with any food—that you have to put it in context of history and culture. And when I wanted to write about the food of the Jews of France, at first I don’t think I knew what I was getting into. The more I interviewed people, and heard their stories, the more poignant the food became as I heard how it survived, and how the civilization has survived.

I think of food as life, and as long as the stories and the food are kept alive, then the culture is kept alive.

Exactly. For example, I read in a 14th century book about a parsley sauce, and a sweet and sour sauce for fish, and Jews in Alsace make them to this day.

I always learn a lot from your books, but this one taught me things I never really realized. For example, I never knew that the technique of gavage was developed in part by French Jews to produce extra cooking fat, since they couldn’t use lard. It totally makes sense. What are some other examples of food creation-by-necessity that we either don’t know about, or just take for granted? – What surprised you?

Ah, the question of the duck: the Romans also made duck fat—I read Cato on agriculture, and learned a lot about who was using what, when, and where. I also learned that the development of Ashkenazic cuisine actually came out of France. If you look at the south of France, that’s where Jewish food really began – there was no Sephardic or Ashkenazic cuisine. But as Jews moved farther north in France, where olive oil wasn’t readily available, they began to use duck fat. And then in the winter, they cured, and pickled cabbage [sauerkraut], which is one of the oldest ways of preserving food. Jews in the south made a bean stew for the Sabbath, but those beans weren’t available in the north. So northern Jews began to make pot au feu, since there were many northern French Jews in the cattle business. Meat was more readily available, and so that became the Sabbath stew. Then, during medieval times, cabbage was added to it. So my guess is that it became choucroute garni.

By virtue of its location, France’s Jewish cooking is definitely melting pot. The recipes in this book, which are utterly mouthwatering, nod both toward central and eastern Europe, and also south, to North Africa. I smiled when I read the recipe for Babka a la Francaise, and the chopped liver pate (which I grew up with, but I’m pretty sure my bubbe didn’t use cognac in hers). How do the very different regional flavors of Jewish cooking in France come together now? Is there cross over? Do they tend to remain separate? Or do the styles of food and ingredients cross regional boundaries? Would you ever find a Jewish family in Strasbourg cooking, for example, North African food?

I think that every person has a religious identity that shows up in their cooking. And I think that in traditional foods – the foods we serve during holidays – these two identities emerge, and it doesn’t matter where you live. Like this one couple I interviewed – she’s from the southwest, but of Polish origin, and he’s from Annecy and of German-French origin — and he always wants Reblochon, and she always wants Piment d’Esplette, she always wants ratatouille, he always wants gratin Dauphinoise. You can see that that’s how proud they are of their regional identities. And I think that a lot of French don’t even realize that they feel that way.

Can you speak to the concept that Jewish food evolved alongside French regional cooking?

Let’s take the south of France; Jews have lived there for 2,000 years. Take a recipe like a fougasse, also from the south: I read that the Jews of the 14th century ate it on Shavuout with butter and milk, and then I found this little Medieval ditty that said “use oil in your fougasse otherwise you’ll be a goy,” because they would have used lard. I thought “oh my gosh. Nothing changes.” In that 14th century book, they talk about fougasse with cherries embedded in it, so I went to Cavaillon and actually saw fougasse with olives embedded in it because it was a different time of year. And I thought “oh, look at this—it’s living history, right here.” It’s pretty amazing.

In reading this, I can’t help but think of my own family. As American Jews, it can be hard to hang on to our traditions. Is it as hard for the Jews of France to hang on to their traditions as it is for American Jews? In France, do you see younger people getting more and more interested in maintaining their culinary culture alongside a growing religious practice?

Oh, absolutely. I think it’s the young people who are really hanging onto it. There’s a very vibrant Jewish community in France, and much of that vibrancy is coming from the North African Jews. I was in one town, and there was a tiny, active synagogue there—it was actually a synagogue when the first Kabbalist rabbis visited. And what’s interesting is that it’s the same way in France as it is in America: I was recently in Virginia Beach — there’s a big Jewish community there. Why? Doctors settled there because of the military, and engineers settled there as well. It’s the same in France, all over, for the same reasons.

You probably get this question a lot, but I’d be remiss if I didn’t ask: what is your favorite recipe in the book? What was your favorite story?

My favorite recipe because it’s simultaneously so old and so modern is the Alsatian Kugel—the pear kugel with sautéed onions — so it’s savory — and then it’s topped with a prune compote. And the babka, which is really like a trompe l’oeil—it looks like what you’d expect a babka to be, and then it winds up being totally different, with a very French touch to it. [It’s made with tapenade. ed.] As for stories, I received an email from a man I interviewed for the book, who had a relative in the 13th century who was a truffle hunter. This man made so much money hunting truffles that it allowed him to become the head of a Yeshiva for the rest of the year. I love that story.

I love all your stories and all your food, Joan. Thanks so much for talking to Poor Man’s Feast, and all the best for a happy holiday.

Moroccan Chicken with Olives and Preserved Lemons

from Quiches, Kugels, and Couscous by Joan Nathan

WHEN CELINE BÉNITAH COOKS THIS DISH, she blanches the olives for a minute to get rid of the bitterness, a step that I never bother with. If you keep the pits in, just warn your guests in order to avoid any broken teeth! Céline also uses the marvelous Moroccan spice mixture ras el hanout, which includes, among thirty other spices, cinnamon, cumin, cardamom, cloves, and paprika. You can find it at Middle Eastern markets or through the Internet, or you can use equal amounts of the above spices or others that you like. To make my life easier, I assemble the spice rub the day before and marinate the chicken overnight. The next day, before my guests arrive, I fry the chicken and simmer it.

4 large cloves garlic, mashed

Salt and freshly ground pepper to taste

1 teaspoon ground turmeric

1 to 2 tablespoons ras el hanout

1 bunch of fresh cilantro, chopped

4 tablespoons olive oil

One 3½- to- 4- pound chicken, cut into 8 pieces

1 teaspoon cornstarch

1 cup black Moroccan, drycured

olives, pitted

Diced rind of 2 preserved lemons

Yields 4-6 servings

Mix the mashed garlic with salt and freshly ground pepper to taste, the turmeric, the ras el hanout, half the cilantro, and 2 tablespoons of the olive oil. Rub the surface of the chicken pieces with this spice mixture, put them in a dish, and marinate in the refrigerator, covered, overnight.

The next day, heat the remaining 2 tablespoons olive oil in a large pan. Sauté the spice- rubbed chicken until golden brown on each side.

Stir the cornstarch into 1 cup water, and pour over the chicken. Bring to a boil, and simmer, covered, for about 20 minutes. Add the olives, and continue cooking for another 20 minutes. Sprinkle on the preserved lemon, and continue cooking for another 5 minutes.

Garnish with the remaining cilantro. Serve with rice or couscous.