Deborah Madison

Back in 1987, I was working in downtown Manhattan as the book buyer at the original Dean & Deluca in Soho. My boss had just returned from a buying trip to the Bay area, and when I asked him where he’d eaten his best meal while he was out there, I expected a certain response, but it was not what I got.

“Greens,” he said, “hands down.” Days later, I received a shipment of The Greens Cookbook, written by the restaurant’s founding chef, Deborah Madison. I could barely keep it in stock.

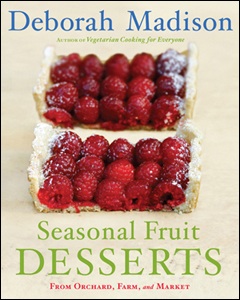

Fast-forward twenty-three (unbelievable) years: Deborah Madison, has produced nine award-winning cookbooks, including the much sought-after The Savory Way, and Vegetarian Cooking for Everyone, which is widely considered a culinary bible and credited with changing the way Americans think about and prepare vegetables. Her long-awaited next book, Seasonal Fruit Desserts from Orchard, Farm, and Market, is set to release on April 6th.

In January, I had the pleasure and honor of meeting Deborah at the first Edible Communities Conference in Santa Fe, not far from where she lives with her husband, painter Patrick McFarlin. Over the course of several days which included getting stuck in the snow at a local goat farm, and a guided trip to the Santa Fe Farmer’s Market, I found myself lucky enough to twice be a guest at her home, where I experienced my first local Navajo-Churro lamb, a whisper-light, elevation-defying olive oil chiffon cake, lovely wine, and even lovelier conversation. We continue it here.

After spending many years cooking from and reading your books, I’ve gleaned three things: your testing process must be incredibly labor intensive (because all of your recipes are precisely delicious, and deliciously precise); you’re a remarkable baker; and you have a real affinity for and love of desserts. So when I heard that your upcoming book was called Seasonal Fruit Desserts from Orchard, Farm, and Market, I wasn’t surprised. Tell me about how you came to write a dessert book focused on seasonal fruit when so many people automatically equate dessert with chocolate.

Maybe because I’m not a chocolate person! I’ve had a big piece of Green and Black chocolate sitting on my desk for several days now and somehow, I don’t even see it. But that’s not really the reason. That bar will get eaten.

I decided to focus on fruit for dessert because, like vegetables, fruit is produce. It’s plants. It’s alive, or at least it should be. I get so annoyed with the government telling everyone to eat so many servings of fruits and vegetables, but doing nothing to address what makes fruit so good that you don’t need to be told. Fruit is the most sensual, luscious, food there is. When it’s the right variety, ripe and truly ready to eat, it does compete with chocolate. No one has to be told to eat a ripe peach, an aromatic, red-fleshed berry, a bowl of sweet cherries. So I wanted to bring fruit to the fore. I wanted fruit to be seen as more than a duty food—the dreary exercise of, say, dropping flavorless plums into a plastic bag without even smelling them to judge their promise. A great Santa Rosa plum, or the gorgeous Coe’s Golden Drop—well, that’s another story.

You are one of the originators of the local food movement in the United States, dating back to your days as the founding chef at Greens (in l979). At that time (the 1970s and 80s), vegetarian food in this country seemed to be unerringly brown and stodgy, and you are credited with dragging it out of lentil nutloaf-dom and into a world of color, flavor, taste, texture, and simplicity. How did you get there? Who were your mentors?

That is a very big question. In fact, that’s the very subject of the book I’m currently writing.

When I first started cooking vegetarian food in l970, there were no books to tell you how to make it beautiful, delicious, colorful. Or just plain good. Vegetarian food was still about austerity and health. It was not about pleasure. The books that were around, like Ten Talents, never introduced a recipe by telling you how much you’d enjoy it. (A dubious practice, in any case, perhaps.) A head note might say there was lots of vitamin C lurking around a dish, but that would be it.

So for inspiration, I turned to Julia Child, the New York Times International Cookbook, Gourmet, and the Time-Life Books. There were lots of enticing dishes that weren’t based on meat, or there were dishes I could reinterpret to be meatless. Before the Italian cookbooks appeared, Waverly Root’s book The Foods of Italy was full of inspiring gestures of dishes, which I tried to fashion into recipes. I also studied Larousse Gastronomique like crazy, pouring over it in search of tips, techniques— anything I might use.

After the mid-l970s a lot of interesting cookbooks started coming out, written by people like Marcella Hazan, Giuliano Bugialli, Diana Kennedy, and Paula Wolfert. Cooking schools were getting started in San Francisco and you could take classes with these same authors. Suddenly, there were lots of places to find inspiration, and San Francisco restaurants were starting to change and everything was getting more vibrant and free. That’s the short answer. Around l977, Alice Waters and Lindsey Shere became my mentors when I started working at Chez Panisse.

When I began working in the food community in the 1980s in New York, the trend was towards preparing, serving, or selling top-quality, highly-exclusive ingredients grown in romantic, mysterious, and often very distant places. Customers and diners craved gorgeous vegetables that had traveled overnight from California; fresh sardines that had been flown in from Portugal; cepes that had been growing in a French forest just a day earlier. That concept of distance-as-good has, thankfully, been turned on its head. It’s a big question that we could chat about forever, but how do you think the local food movement has evolved in this country, and where do you think it’s going?

I was just talking with Caroline Bates, who wrote for Gourmet for 40 years, about how French chefs in Los Angeles looked down on all local foods, wouldn’t use Pacific fish, and flew everything in from France. This was in the l970s so there probably wasn’t a lot of great produce here then, the way there is today.

I think that the appearance of farmers markets had a lot to do with the shift towards fresh and local foods as being the foods to eat because the markets were fun to go to and once you got there, there was all this beautiful produce to buy and it looked so bouncy and vibrant and tasted so much better than what you could buy in the store. But one also has to look at the restaurants (I’m thinking about the California restaurants in the late l970s and l980s—Chez Panisse, Hayes St. Grill, Fourth St. Grill, Greens, etc.) because that’s where many people first encountered what I think of as “the new produce” — the little lettuces, the fingerling potatoes, arugula, golden beets, and so forth. Those restaurants gave the shopper a clue about what to do when they found those same foods at the farmers market because they had already encountered them.

The farmers market was all about local food. Now of course, the idea of distance is getting tweaked all the time. Is it U.S. grown? Regional? From within this or that distance? Your backyard? I think people realize that the closer that something is grown to your kitchen, the better it is, but of course that represents a challenge for lots of folks.

Your overarching message has always been one of freshness, locality, and simplicity. But how do cooks who live in northern climes (like myself) deal with painfully short growing seasons? I love turnips and rutabagas, but not eight months out of the year. What is a New Englander (or Midwesterner) to do, especially if we have no access to year-round CSAs or farmer’s markets?

I have sympathy with this since I live at 7,000 feet and today, on St. Patrick’s Day, there is still snow on the ground. If you’re really trying to eat purelylocally, boredom with root vegetables would be a good argument for canning and freezing summer produce. Also, growing a wider range of root vegetables might help. It’s so hard to find salsify, or Hamburg parsley, or celery root, all of which are such good additions to the winter kitchen.

I guess I’d have to say that I’m not a pure locavore. I’m in a more moderate camp—the one for non-Californians. I think it’s hard to wean ourselves from the practices of generations, so I am more inclined to take the gradual path rather than the steep, cold turkey path, although that’s an interesting exercise, for sure. It really makes you grateful, for one, for whatever variety you do have.

My practice is to buy what’s local, then supplement, but with as much care as possible. Which means I buy from the farmers I know of who are smaller scale farmers doing good work. And I buy from those who are closer, not farther away. If you look at the twist-ties at your local co-op, you can usually find a web-site for the farm that grew those carrots or whatever, then you can see if it’s the type of operation you like and want to support, even if shipping is involved.

I also want to mention that farmers can learn to extend their seasons. I know you’ve told me about how short your farmers market season is and ours was once that short as well. Now our market goes year around, and it’s not because of climate change! Farmers have become adept with hoop houses and grow tunnels. They have gotten better at storing their produce so that even now, in winter, I can buy all kinds of root vegetables, apples, and a variety of greens at my market along with the beans, chile and posole. Even my own covered beds are giving me lettuce, chard, spinach, and turnips. It’s not gorgeous looking, but it sure is fresh and it tastes wonderful.

Many of your readers and fans have assumed over the years that you are a vegetarian, having authored what is probably the greatest book on vegetable cookery ever penned (Vegetarian Cooking for Everyone). How often do you eat meat, and what are the parameters you use for deciding what is okay, and what isn’t?

First the parameters: I eat meat when it’s kindly served to me in someone’s home. I eat meat when I travel if that’s what there is. I sometimes order meat in a restaurant, but most frequently I order the vegetarian option. It depends. I might prefer wild salmon to a cheese-dense something. If I buy meat, it has to be from a local rancher I know and whose practices I’m familiar with. I also have neighbors who are ranchers and our farmers market offers a lot of grass-finished meat, so as for quality, scale and good practices, there is a lot available. I never buy meat from the supermarket and never have as I don’t want to participate in supporting industrial meat in any way. The ranchers I know have small herds and good animal husbandry practices. We are not talking CAFOs in anyway at all.

As for how often? Once a week or less? We mostly eat vegetarian because we prefer to, but occasionally my husband will sometimes say he would like to have a steak. (I’m not a steak eater –I’ve never have gotten into it as I didn’t grow up with it.) I often cook a special meat for visitors, like the Navajo-Churro lamb I made for you, because it’s something people have never tasted before. It comes from 5 miles away. We have a farmer who raises amazing chickens using the French protocol, Label Rouge, which I will serve to company. It’s very expensive and a treat and such a good example of doing chicken really right that I want people to experience it first hand (and maybe go home and encourage a chicken farmer to give it a try.)

I’m not a hugely enthusiastic meat eater, but occasionally I do have a deep hunger for it which I acknowledge. Having been a vegetarian for about 20 years, I can say that I didn’t do too well on that diet. I love the food, but I didn’t like always coming down with or just getting over a cold or flu. That hasn’t been the case in a long time and I think that quality of protein helps. But I also keep in mind, that nothing wants to die. That never escapes my thoughts.

Living in the Santa Fe area, you have access to one of the nation’s best year-round farmer’s markets; you also have an active vegetable garden. How do you decide what to grow, versus what to buy?

It’s easy—I buy what I can’t grow. I’m pretty good with lettuce and peas, greens and squash, turnips, potatoes and Jerusalem artichokes—easy things, basically. I find broccoli and cauliflower intimidating. Tomatoes are hard for me because I have a lot of shade, but I grow the smaller varieties. I plant zucchini despite the icky squash bugs, because I happen to love Costata Romenesco and no one sells it at the market. I grow shishito peppers because I don’t want to pay $10 a pound for them at the market. The same is true of green beans. Actually, the more expensive our market gets, the more I want to grow my own food. But I don’t have a farm; I have a smallish garden.

It’s July 2010 in Galisteo. What’s growing in your garden this year, and what will you do with it?

Give our altitude and my shade, I’ve got chard—all kinds— and turnips, radishes (also all kinds), spinach, lettuce, and the arugula is in flower but is still good to eat. It’s a bit too early for squash, tomatoes and shishito peppers but beans should be coming on if the mice didn’t eat them—always a problem. What I’m really happy about are the herbs: the lovage is a tad ratty looking but still pretty good, the chives are in bloom; there’s chervil, young oregano, the first marjoram, and epazote for beans, which I adore when it’s fresh. They thymes are very useable, the salad burnet is right on time to drop into a glass of Hendrick’s Gin along with some rose petals. Oh yes, and parsley. It’s so good when it’s super fresh. I know there are herbs and vegetables that I am missing because as I look outside, everything is so brown and dull. The sage will be blooming and the rosemary (faintly), but I give them a rest during the summer since I use them so much in the winter. There might be some basil, and of course, sorrel, which is already up and looking very tempting, though tiny.

You are a longtime advocate of seed-saving; why do you deem this so important?

That doesn’t mean that I’m necessarily a seed saver, although I do save some, mostly things like larkspur and arugula and lettuce. I like to support seed businesses, like the Seed Savers Exchange and also my local nurseries. But someone has to save seeds or we won’t have these amazing resources to fall back on, if the need arises. I’m thinking of the serious seed banks, like the one in Svalbard—not someone like me putting some seeds into an envelope to use the following year. But in between, there are some skilled individuals who have saved seeds and passed them onto people. I’ve had the pleasure of being a recipient of such seeds through friends and local seeds exchange, and some of those seeds have been some interesting old varieties of chiles that grow around here. (Members of Seed Savers Exchange can have access to a great seed exchange.)

Quick question: cast iron, or copper? (Or neither?)

Both! But also clay. Especially micaceous clay, which is used traditionally in the Rio Grande Valley. I adore cooking in my micaceous pots. They smell so good when they’re hot, and food cooked in them tastes especially good somehow. They’re handsome to look at. They’re strong and light. They’re also made by hand and I’m very aware of whose hands shaped and rubbed and sanded them since I happen to know the makers.

What’s for dinner tonight?

Hmmm. I’m going to go pick chard and spinach from my covered beds and use that in a thick lentil soup with lots of cilantro, and cumin. I’ll be eating that for a few lunches this week, too. But I also want to cook broccoli rabe, which isn’t from my garden. It’s my favorite vegetable, or one of them anyway, and I’ll probably do a pretty classic pasta dish, though on my own, I’d be happy just to eat a plate of the rabe. In fact, maybe we”ll do that anyway—cover it with some crisped bread crumbs. Let’s see, there’s a fine dice of cooked golden beets leftover from Friday night – might have that as an appetizer or a salad with some arugula (also from the garden) chopped into it. The arugula is pretty peppery so it won’t take much. Some leftover persimmon pudding from last night’s dinner party for dessert. This is the last of my frozen persimmon puree. I also put the last of my Medjool dates in it. Darn, why didn’t I suggest that in my dessert book?

From Seasonal Fruit Desserts from Orchard, Farm, and Market

This electric orange pudding is great for someone who’s longing for dessert but trying to say no. Tangelos are big and juicy with a decidedly round and sparkly flavor, but any tangerine-type citrus at its sweet prime will be a good bet. A mixture of citrus—grapefruits, tangerines, blood oranges, a bit of lime—is also intriguing, a kind of tutti-frutti. Or use just blood orange juice, if you can find it.

This electric orange pudding is great for someone who’s longing for dessert but trying to say no. Tangelos are big and juicy with a decidedly round and sparkly flavor, but any tangerine-type citrus at its sweet prime will be a good bet. A mixture of citrus—grapefruits, tangerines, blood oranges, a bit of lime—is also intriguing, a kind of tutti-frutti. Or use just blood orange juice, if you can find it.

If you choose to use bottled juice, look for one that is freshly squeezed, if possible. I have occasionally found some fine juices at farmers’ markets and farm stands where citrus are plentiful.

Makes four 1/2-cup servings

1 heaping teaspoon finely grated tangerine, tangelo, or other citrus zest

1 tablespoon organic sugar

3 tablespoons organic cornstarch

2 cups fresh tangelo juice (from 10 to 12 tangelos) or mixed citrus juice

Tiny pinch of salt

1 tablespoon unsalted butter

1 teaspoon bottled yuzu juice or 1 tablespoon orange-flower water

Stevia, orange blossom honey, or agave nectar, to taste

1. Smash the tangerine zest with the sugar to moisten the sugar with the fruit’s aromatic oils. Transfer to a 1-quart saucepan along with the cornstarch, juice, and salt. Stir to dissolve the cornstarch.

2. Turn on the heat, bring the mixture to a boil, and cook, stirring, until the juice has thickened, after just a few minutes. Cook for 1 minute more, than turn off the heat and whisk in the butter and yuzu or orange-flower water. Taste, and if extra sweetener is needed, add a few drops of stevia, orange blossom honey, or agave nectar.

3. Divide among juice glasses or Champagne glasses. Refrigerate until set, about 2 hour. (If you’re not counting calories too quickly, this pudding is great with a dollop of whipped cream.)