It’s the past that tells us who we are. Without it, we lose our identity. – Stephen Hawking

It was an early spring night when I incinerated the chicken.

Weeks earlier, I grilled a steak — a nice, grass-fed porterhouse the price of a Fiat — so well-done that you could snap it in half like a charcoal briquette. I’ve poached dozens of eggs to the point of bouncing; carbonized my morning toast; steeped my green tea until it was so bitter that it made me cry. At Easter, I roasted a local, acorn-fed ham until it collapsed into cords of floss. On Passover, I took pains to make a rich, robust chicken soup and then served it lukewarm with cold matzo balls, brisket that fell apart because I’d sliced it with the grain, and half-done sweet potatoes coated with a balsamic drizzle so cold it made my teeth hurt. Our guests were very kind, even though I somehow decided that it would be a nice idea to not open the incredibly lovely, short-run, signed-by-the-winemaker magnum of Pinot Noir they brought for the occasion. With dessert — Susan, thank God, baked an almond cake — I served them watery Mokas in tiny Duralex glasses, which made them look like thimblefuls of rainswept mud instead of espresso.

Does Emily Post have a chapter for this? Susan whispered to me when we were clearing the table for the second course.

For months, everything I’ve touched in the kitchen has turned to shit. My domain — the place where (next to my desk) I’m most tightly tethered, and where I best know my own identity — has felt as alien to me as Mars. The feeling comes as a familiar, discomfiting clench in my chest; a distinct but subtle panic not unlike the attacks that addled me from the time I was a child and sometimes, when I’m not taking care of myself, still do. There’s been a disconnect that I can’t put my finger on; it’s like I’ve unplugged the phone but I keep trying to make a call. On more than one occasion, I mixed up the dogs’ food — they eat two different kinds — and scooped a dollop of cat food into my terrier’s bowl. For months, I couldn’t feed Susan, my friends, my extended family, my animals.

Myself.

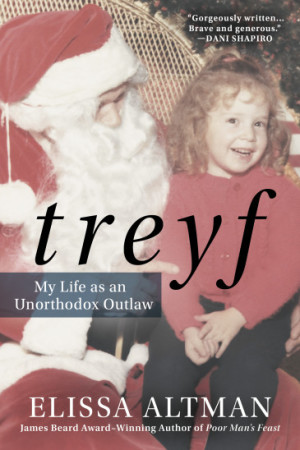

As I write this, I am a little less than four months away from the publication of my next book, a story of growing up in ’60s and ’70s Queens New York, always on the outside looking in, living life as a chronic misfit searching for grounding, security, family, and a certain way to nurture and sustain myself. Anyone who grew up in Queens back then knows full well: it was a crazy time, sandwiched one end of the decade by the Kitty Genovese murder and on the other by Son of Sam, the ’77 Yankees, Studio 54, Earthquake in Sensurround, key parties, bad hair, and The Partridge Family. It was a time of change — unfathomably rapid change — that left many of us so-called good girls in the position of having to choose between the people we were raised to be by our 1950s forebears, and the people we were destined to become. And as I wrote Treyf, I realized that this choice-making — often rule-breaking — was not just a function of the 1970s, when nothing was off-limits; piloting the waters of the (culturally, Talmudically, culinarily, emotionally, sexually) proscribed is what humans do, putting one foot in front of the other and schlepping forward into the future, into the unknown, into a world that is constantly shifting around us. Treyf is the story of this navigation, of stepping into the future with a need to cling to the past. It’s about the leaps of faith that we all have to take as we negotiate the universe; it’s about becoming inveterate rule-breakers — all of us, even our parents and grandparents — in the face of tradition even as we long for the security and supposed safety of that tradition. In order to evolve and become our true selves, we can’t do anything else, no matter who we are or what we’ve been raised to be.

And where there is rule-breaking, there is inevitably conflict; this is the way of the world. What was the feeling in the pit of my twelve-year-old grandpa’s stomach when he ran away from his small Ukrainian town in 1905, leaving his mother and siblings behind with the stepfather he hated? Would he stay or would he go, and escape the fate that they met when the Nazis arrived, forty years later? How did my Orthodox-raised father feel when he subversively made me Spam and eggs for breakfast one Saturday morning? At a time when I was raised to marry a doctor or a lawyer, did I dream of marrying a poet or a painter, a man or a woman? There were other choices to make in the writing of the book: would I tell my story transparently, or would I hide my story? Would I carry forward a constellation of genetic shame strapped to my back like a tortoise shell, or would I release it to the waters of time?

Treyf is a story of grief and love, longing and forgiveness, of ultimately finding peace in a world laced with hope, the forbidden, and the eternal yearning for acceptance. There is a considerable amount of food in it — my beloved paternal grandmother fed me a cold, boiled brain on a plate the day after I saw the premiere of Young Frankenstein at The Ziegfield in 1974; all I could think of was Abby Normal. In Treyf, food is the grounding wire and the anchor; it is the silent collaborator in the story, the one who watches the tribe increase and the decades unspool and the rules be broken, repeatedly; food lures and betrays, beckons and soothes, and connects the present to the past in an unending loop.

To write memoir is to smell and taste and see things that exist only through a veil of memory and the specter of time. The risk is profound, and requires such focus that it’s very possible to lose the present, the here and now, while you’re busy trying to understand how you got here. The present becomes as much a ghost as the past; you wind up living in neither.

I incinerated the chicken because cooking is meditation; it requires — demands — full presence in the here and now, the gap between what was and what will be. And as anyone who writes memoir will tell you, it is an act that leaves you raw and a little bit shaky and discombobulated. In writing Treyf, I reached out across the decades and reacquainted myself with the thing I once was — the teenage misfit, the outcast, the one who scribbled notes in piles of composition books while the fondue party raged in the next room — unable to cook, to feed myself, to make sense of the world, and ravenously hungry for the future to arrive.

The writing is done now, and I’m stepping back into the kitchen to begin again, to start again, to feed myself and the people I love with presence and care.

How to Cook a Hard Boiled Egg

These days, there are many on-trend ways to cook an egg: there’s the seven-minute egg (very nice in ramen), the poached egg (excellent on buttered toast or atop a pile of wine-braised black lentils), or the scrambled egg (which tends to be overcooked to the consistency of, as Laurie Colwin once described it, an asbestos mat). I’m starting here because this is my nursery food; I make it when I’m in need of (no pun intended) coddling and a quick hit of protein. There are as many ways to cook a hard boiled egg as there are cooks, but this method has never failed me. If you’re cooking for a crowd, increase the number of eggs, the amount of water, and the size of the pan exponentially; the method and timing remains the same.

Makes 2 hard boiled eggs

Place two not-fresh eggs (2 weeks old is ideal) in a medium saucepan large enough to allow water to circulate around them. Fill with water to cover the eggs by an inch. Bring to a boil over medium high heat, slap a cover on the pan, and immediately remove it from the burner. Let it rest, covered, for exactly 12 minutes. Drain the water and run cold tap water over the eggs for exactly 1 minute. Drain, peel, and eat, sprinkled with Maldon sea salt, or even better, dukkah.

Can’t wait to read the book!

Your blog is as pleasurable to read as you are for a chat. It was a treat meeting you some months ago in Vermont and I look forward to future posts.

I wonder who hasn’t incinerated or served raw or cold one thing or another. But I also wonder how many people admit it and see it for what it really is? Treyf

is going to speak to many, I believe. Thank you, Elissa, as always, for your keen insight and honesty.

I enjoy reading your posts. Your style is very heartwarming. It makes me feel like I am seven, sitting on the red velvet couch (no slip covers) reading and hoping no one would find me. Looking forward to reading treyf.

Thanks so much Judith-

I neglected to add “and then I overcooked the leg of lamb dragged by my rockstar friend from the other side of the country to Maine in her suitcase…..”

🙂

Thanks Tom-

Elissa, thank you for validating the toll the writing process takes on a person–and, worse, the punishing, horrible, disorienting, maddening period of reintegration we have to suffer through once the work has been turned in.

I want some eggs now.

Presence. It’s often wherever you left it. Never in two places at once, especially when one place is the past.

Having been in both places with you, you know I’ll be there.

Wherever.

Older eggs boil best? There must be a metaphor there.

Thank you –x

It’s quite the roller-coaster ride, isn’t it? xxx

I can completely empathise with that.. I’ve had to leave my husband for work abroad for a few months and by god, I cannot seem to make anything good despite being an “expert” back home. I used to be able to proudly cook for others now I cannot for myself.I am sure your book will leave me hungry for more.

My beautiful French grand daughter taught me the art of eating a some what soft boiled egg from an egg cup, delicately cracking the shell in just the right spot as to open only the top of the egg and eating it from the shell…I will only eat my eggs that way as they seem to be velvety soft and creamy.

I neglected to say it took me all summer to master….

You blog is so good to read !!!

{ 1 trackback }