I always assumed that my parents got divorced because my father loved food, and my mother didn’t. (She still doesn’t.)

When I was very young, she would go off to the beauty salon on Saturday mornings and say to him, “give her a snack around noon—” My father would nod silently without looking up, and finish doing the Times crossword puzzle. And a few hours later, he and I would be sitting together, having that snack at Luchow’s, or Le Perigord, or Cote Basque. I grew up thinking that the gefilte fish my grandmother gave me each time I visited was also a snack, and therefore so were the quenelles at Le Pavillon.

But my father was an egalitarian sort of guy; he would be just as happy to wave goodbye to my mother as she grabbed her Vuitton totebag and headed out for a touch up and trim at Vidal Sassoon, load me up into the Buick and drive me out to deepest Brooklyn, to Brennan & Carr for a small trio of jus-drenched roast beef sandwiches (two for him, one for me), or Randazzo’s in Sheepshead Bay for platters of baked clams. If her appointment was really early and there was no time to sneak out to the city and back before she returned, we’d wind up at Ben’s Best on Queens Boulevard, where my father introduced me to their Specials platter: two immense, kosher beef franks with the girth of the transatlantic cable, nestled in a snood of baked beans. Sort of like the cassoulet we’d had together one bitterly cold day at the Brasserie. (Sort of.)

But wherever we went, before we walked back through our front door, my father, who carried a pocket-sized lint brush in the car, made sure to subversively remove any telltale crumbs from the black velvet Scotch House blazer I’d always wear if we were going fancy, or the red knit poncho I’d put on if we weren’t. Just to be safe.

“Did you remember to give her a snack?” my mother would ask him in the late afternoon, when we all met up again in the apartment.

“What do you think?” he’d reply, pouring himself a small Dewars.

My father’s taste in food ran the gamut from the sublime to the insane: he could rattle off the mother sauces — Bechamel, Veloute, Espagnole, Hollandaise, Tomato — without hesitation, which doubtless impressed his dates during his bachelor, ad man years in the late 50s and early 60s. He could polish off an entire jar of his mother’s griebenes — crispy rendered chicken skin and onions also known as Jewish Crack — in seconds, and then go out for the sauteed partridge and foie gras at Lutece. He would take the dog out for a walk early on weekend mornings and come home with a can of Spam (which the dog thought was for him) and fry it up for breakfast in thin, rectangular slices; he’d top it with a soft boiled egg, set the whole thing on a pillowy Dumas croissant, sit me down at the breakfast counter and hand me a knife and fork, all under the disdainful eye of my iceberg salad-eating, tall and thin, fur model mother who was convinced, rightly, that I’d be scarred for life.

Years later, after the divorce — after the magazine he started failed, after the Summer of Sam, the blackout, the gas shortage, the garbage strike — when I was old enough to spend part of each August working for him in the small advertising agency he’d founded, he was still given to culinary extremes: we’d go out for lunch together to a dimly-lit Irish dive across the street from his office on Second Avenue and 42nd Street, for the special corned beef and cabbage lunch which had been sitting for hours in a lukewarm chafing dish, and then, if it was Friday and I was spending the weekend with him, for the holsteiner schnitzel at Luchow’s.

One afternoon, he took me to the Belmore Cafeteria, where we sat among cabdrivers eating cheap plates of white toast and eggs and bacon; a gray-haired, wild-eyed woman sitting next to me rested her chin on her chest and mumbled intermittently, while eating a sundae with a Maraschino cherry on top.

My father looked around, embarassed. He never understood that high food or low, Pavillon or truck stop, it just didn’t matter to me: I loved him, wherever we ate. And because of him, I also loved the escargots and the Spam, the quenelles and the baked clams, the foie gras and the franks, the knishes from Queens Boulevard and the all-butter croissants from Dumas.

“Do me a favor, Lissie–” he said that day at the cafeteria. “Don’t tell your mother about this—”

“It’s okay Dad,” I told him. “I never do.”

Luchow’s Holsteiner Schnitzel

(From Luchow’s German Cookbook, by Jan Mitchell, c.1952, Doubleday)

As a child, I ate virtually anything my father put in front me, with the exception of sweetbreads, trotters, and Holsteiner Schnitzel. The latter practically killed him because the dish — Wiener Schnitzel topped with fried eggs and anchovies — was his absolute hands-down favorite. At the time, I couldn’t get beyond the combination of meat and soft-fried eggs, but today, I often crave it. Although I don’t eat much (or really any) veal anymore — that’s mostly a recent thing — if both Luchow’s and my beloved Dad were still around, that’s where I’d take him for Father’s Day: just him, me, and — if I was going to see my mother later in the day — a lint brush.

Happy Father’s Day Daddy, wherever you are.

Serves 4

4 6-ounce veal cutlets

1 teaspoon salt

1/4 teaspoon pepper

Flour

5 eggs

1 cup bread crumbs

6 tablespoons butter

8 or 12 anchovy fillets

8 thin slices pickled beet

4 or 8 slices dill or sour pickle

Wipe cutlets with damp cloth. Pound meat thin; season; dip each cutlet in flour. Beat 1 egg. Dip cutlets in this, then roll in bread crumbs. Cook in 4 tablespoons butter until golden brown on both sides.

Fry the remaining 4 eggs in 2 tablespoons butter.

Remove cutlets to a warmed serving dish. Place fried egg on each; garnish with anchovy fillets, sliced beet, and pickles.

What a beautiful piece and tribute to your very catholic-in -his-taste, Dad.

Loved it.

Thank you—

Loved this piece. Growing up in NYC, Sunday night was Chinese food night. My dad was especially partial to a Cantonese lobster in black bean sauce at an upstairs joint, Joy Luck, on Mott St. I still remember the flickering neon outside the window. We continued the tradition for years, though the restaurants changed. I now favor a Szechuan joint outside of Washington, and yes, on Sunday evenings.

That was great. You write such lovely prose. Thanks.

My favorite so far. So perfectly wonderful. Yeah Dad!

Thanks so much—-

Lovely! Made me think of Saturday afternoons with my dad eating King Oscar sardines on white bread and dipping the bread in the leftover sardine oil. 😉

Hi Lissie. You brought back many memories of my childhood eating with my mother and grandmother across the city. My grandmother was a CPA and she’d do the books for many restaurants. The owners were always happy to accomodate us but not necessarily our penchant for “sharing,” which was not especially favored at The Four Seasons where we’d pass plates around and dive into each other’s food with our roving forks.

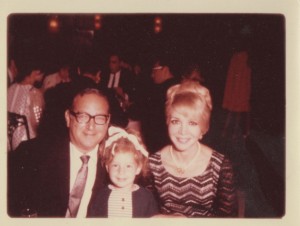

Love this post. I’m pretty sure it was a story about your father that first made me aware of you/your lovely writing. The photo is priceless, too. You have the very same je ne sais quoi in your eyes when you smile. It’s a sort of look that says “how lucky I am to be having all this fun” with a hint of “hope no one finds out” – it’s really lovely. Your mother might be happy to hear that I’m also jealous of her perfect collar bones but don’t tell her I’d never sacrifice gribenes for them!

That was an absolutely beautiful post and so, so well written.

Thanks so much Julie-

Oh, Elissa. The tears started coming after paragraph two. You have such a way with food and memory – and now I know why it’s always so sweet. My dad made me breakfast every day, because A. he was an out-of-work actor and B. my mother never emerged from her boudoir until noon. Every day he asked me (hopefully) what I wanted, and every single day, I wanted “Weenie-and-egg!”

Sounds like we have more than a love of duck innards in common, my lovely friend. Keep it coming, please.

Thanks Brigit–hugs to you.

Thank you so very much for this beautiful tribute to your dad and all of our dads.

What a great story, and beautiful memories. I loved reading this.

I love this so much, and I love thinking of you as that little girl. I have absolutely NO eating-with-my-parents memories — my parents didn’t think of food in that way — but I’m pretty sure that when Charlotte looks back on her life, food will be woven throughout. Thanks, E.!

Laughing out loud, both at your beautiful story and Ms. Madison’s comment!

Lovely! You’re very lucky to have had a Dad who wanted to spend his Saturday;s with you.