It should come as no surprise that the single most popular dish prepared and eaten during the Jewish calendar’s mystical High Holy Days is brisket. To take an otherwise tough and unforgiving piece of meat and render it tender and yielding requires that the cut — which comes from the part of the animal directly adjacent to its heart — be treated with the utmost care and attention, and cooked long and very gently in a warm oven, with the addition of fragrant aromatics. The process, in the culinary scheme of things, seems to take forever, but not too long; if the oven is hot and angry, the meat will cook too quickly and the result will be impenetrable as shoe leather. If the oven is cold, the meat will cook too slowly, and the end result will be submerged in its own heart-stopping fat, like confit. Cooked perfectly, temperately, with extremes of neither hot nor cold, brisket achieves a certain delicate texture, a kind of sweet, unctuous essence arguably found nowhere else in meat cookery.

Historically, brisket leftovers are folded into small pockets of dough for the last meal to be eaten before the Yom Kippur fast; the meat represents severity, the dough, kindness. Eaten together in soup as kreplach — dumplings — the marriage of these extremes embodies the vagaries of the human condition and challenges of the heart: the severity that is always present — we’re all capable of it — and the kindness without which our life, like loose shards of meat, falls apart, and is unendurable.

When making brisket, as I do once a year, it’s the sweet tenderness that we strive for, that comes only with thoughtful focus and near-meditation; my grandfather keened and wept in his synagogue, lost in thirteenth century Kabbalist orison while my grandmother keened and wept in her kitchen, lost in culinary prayer. The results they hoped to attain were the same: mercy, peace, wisdom, health, life, tender sweetness.

My grandfather spent hours davening; my grandmother spent hours making her brisket. Once, my father brought me to the synagogue where my grandfather was a cantor — he had a magnificent voice — and I, not yet five, was alarmed that we were immediately separated upon my entering the building; I was brought upstairs to the Ezrat Nashim — the place where women sit separate from the men — until my father came and carried me back down the center aisle of the shul like a baby. My grandfather, deep in prayer, his eyes closed, couldn’t, wouldn’t see me, and I cried.

Here, my father said, he only sees God.

When we left and returned to my grandmother’s house, we found her in the kitchen, lost in culinary bliss, head down, making precise slits all over an immense brisket, inserting exactly two — never one, never three — slivers of young garlic into each tiny opening. She vigorously massaged the meat with oil like she was readying a boxer for the ring, and seared it in a long, dry pan; a thick plume of smoke enveloped the room — her ancient Tzedekah boxes disappeared into a cloud of melting beef fat — and the brisket sizzled like the sound of rain on a metal roof. After the searing came the addition of a juice glass of water; the careful double-wrapping of the pan with heavyweight foil; the insertion into the oven; the cooking for four hours; the chilling overnight; the skimming of the fat; the slicing; the re-covering with more foil; the returning to the oven. She was a minimalist.

Twenty-four hours after we arrived in her apartment, my grandmother’s brisket was ready. Nearly a week later, shards and shreds of leftover meat were tucked into kreplach dough for the last meal before atonement, before the prayers for mercy, before the severity and the kindness, and the profound hope for tender sweetness.

A few years later, I asked her What is brisket?

She put her hand on her chest, between her breasts, and closed her eyes.

This is where it comes from, she answered. The place where the heart is.

New Year’s Brisket

Over the years, I have attempted to make brisket in any number of ways: I’ve gone minimalist (like my paternal grandmother), I’ve braised it in Heinz Chili Sauce (like my lovely cousin-by-marriage, Roberta), I’ve added Coca Cola to the mix (a Jewish Southern tradition; when the Coke cooks down it leaves a hefty amount of residual sugar and caramel flavor), and invariably, I always come back to this version, which feels the most traditional to me because it’s more along the lines of how my maternal grandmother, Clara Elice, used to make it (she was of Hungarian lineage, and her food tended towards the strongly flavored). Brisket aficionados (the ones without cholesterol concerns) will tell you to ask your butcher for 2nd cut brisket, which is far fattier than 1st cut (which is what I prefer because it’s simply beefier and stands up to longer cooking). Either way, the key is long, slow cooking, an overnight rest in the fridge, and then a brief re-heat the next day before serving. Leftovers— the “strings and shards of meat” — can be folded into dumpling wrappers if you don’t want to go to the trouble of making your own kreplach dough.

Serves 4, with leftovers

1 4-pound first cut brisket, trimmed of some excess fat but not all

1 garlic clove, peeled and slivered

salt and pepper to taste

1 tablespoon grapeseed oil

3 medium onions, peeled and thinly sliced

1 cup dry red wine

1 16 ounce can plum tomatoes, smashed in their own juice

3 medium carrots, peeled and sliced on the bias

2 celery stalks, sliced on the bias

1 bay leaf

2 sprigs each rosemary and thyme

Bring the brisket to room temperature, place it on a cutting board fat-side down, and using a sharp, thin knife — I use a filleting knife — make small slits (no more than 1/4 inch long) all over the meat, and insert 1-2 slivers of garlic deeply into each slit. Salt and pepper the meat on both sides and massage it with the grapeseed oil.

Preheat oven to 300 degrees F.

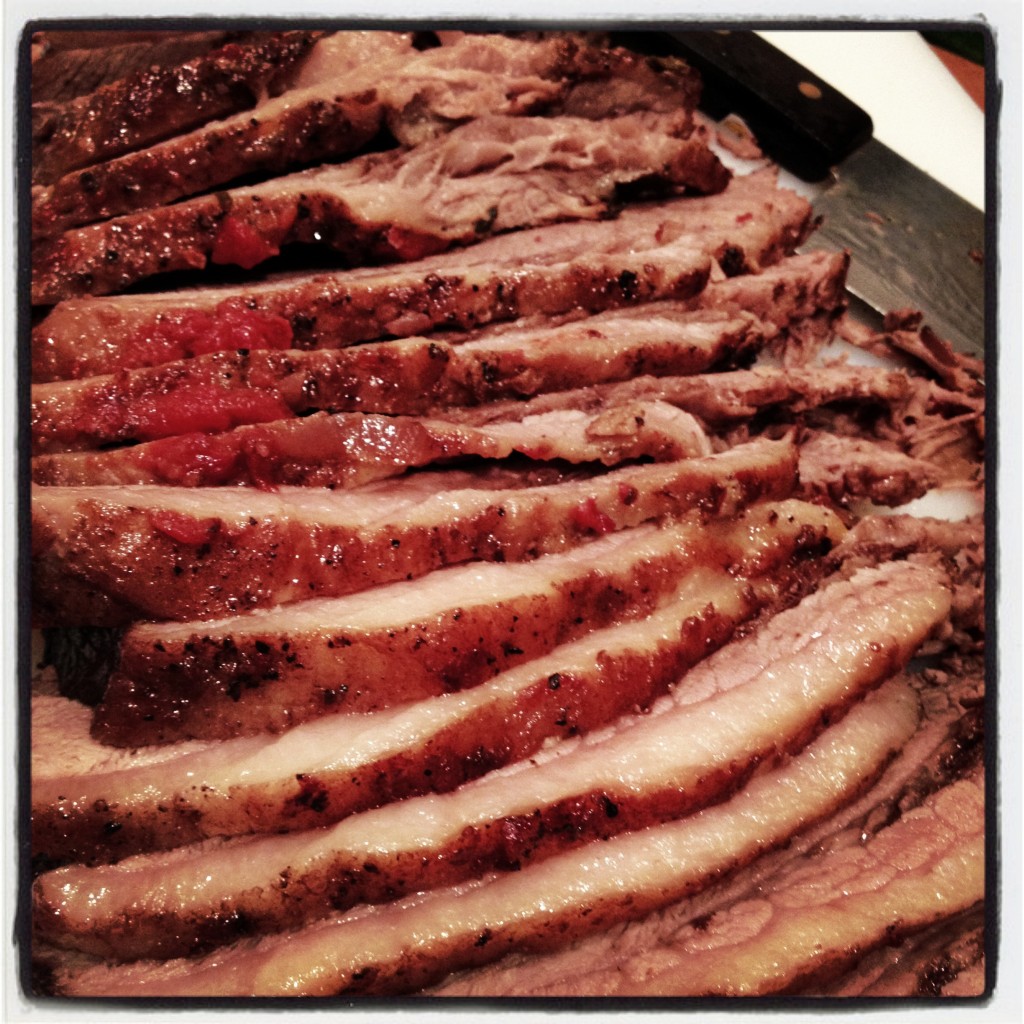

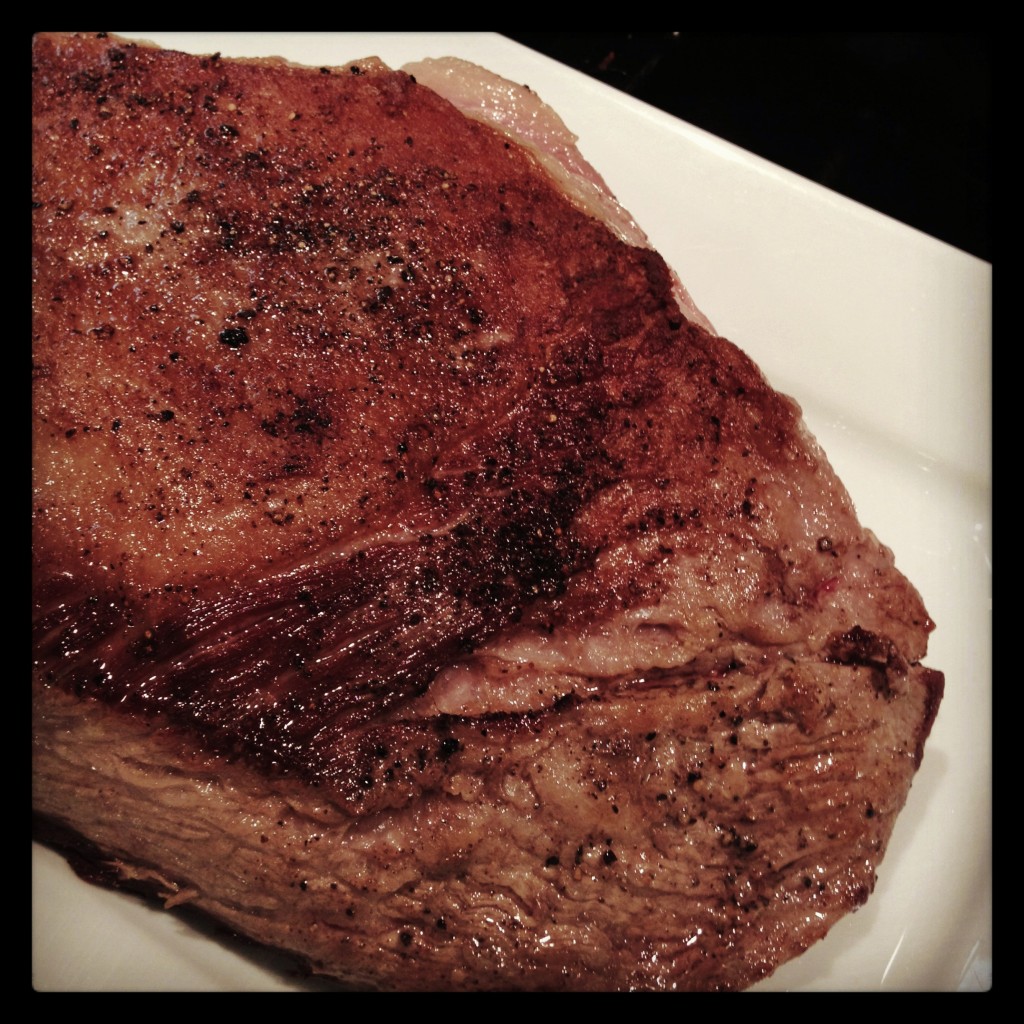

In a large, heavy, straight-sided, non-reactive saute pan with a lid (you can use a shallow, fire-proof roasting pan too) set over medium-high heat, brown the meat fat-side down, about 5-8 minutes. Turn the meat over and repeat; you should wind up with a good, strong golden brown crust as in the image above. Remove, set aside, and add the onions to the pan. Toss well until they’re coated with the fat, and return the meat to the pan, setting it on top of the onions along with its accumulated juices, skin-side down.

Add the wine and tomatoes to the pan, cover tightly — if the pan doesn’t have a cover, tightly wrap it in heavy duty foil — and place in the oven for 3 hours. Baste the meat with its juices frequently. After 2 hours, add the carrot, celery, bay leaf, rosemary, and thyme, and continue to braise for another hour, basting frequently.

Remove the pan and allow to come to room temperature; place in refrigerator, covered, overnight.

The next day, skim all of the accumulated fat from the pan; remove the meat from the pan and slice it carefully across the grain. Return it to the pan, and reheat, covered, at 300 degrees F until tender. Serve hot, or at room temperature.

Love this!

I will think of this whenever I eat brisket. My family never quite made it to the kreplach stage, but this custom offers up such beautiful continuity. Shana tova, G’mar chatima tova – Have a happy and healthy year to you and your family. I know this one has been a rough one.

I wonder how long I can get away with blaming my head injury for misty eyes.

I love your grandmother. Thank you for this.

Wishing you both a lovely, wonderful New Year, and if you’re fasting, an easy fast. That is some stunning brisket you’ve got there.

What a wonderful story to accompany a beautiful dish. I have to try and make kreplach, they sound delicious. So I’ll be making slow, slow brisket. Thank you. GG

Just beautiful!

Thank you so much, Glamorous.

Thanks Dena-

Thanks Olga—

That was a beautiful piece. Thank you for sharing!

I see my grandmother as I read about yours. Her brisket was made on top of the stove, and with the addition of onions. Otherwise, it was exactly the same. I thank you for this reminder of a delicious past. L’shana Tovah.

Heavenly prose on a topic I couldn’t imagine there’d be so much to say. L’Shana Tova.

Thank you Diane-

Thans Shirley

Your writing is just so beautiful. I’m ashamed to say that I know nothing about Jewish traditions. I am learning, though, from your beautiful images and through reading your words I experience your life. Thank you for sharing.

Written from the heart, Elissa. A truly poetic food memory from childhood…”and the brisket sizzled like the sound of rain on a metal roof.” Kreplach and brisket, linked by tradition.G’mar Chatima Tovah!

OK – how do I learn to make that beautiful brisket?! Thanks for your wonderful writing and sharing your traditions. My family’s are different, but so much

the the same.

I am sitting here with tears…such a beautiful post. You brought back such sweet memories to me…of relatives so loved and now gone…the scent of the holidays…my Bubbe sitting at the top of the steps with a wooden bowl on her knees …chopping horseradish with tears running down her cheeks

A happy and healthy New Year to you and yours….

Thank you…

And to you, Linda—thank you.

Anita, recipe is attached! Enjoy!

Beautiful and heartwarming. I hope these days of awe have filled up some part of what the last many months have depleted from you and Susan. (That brisket should certainly help!) I love, by the way, the side-by-side posts about the fancy-food pig experiment and the near-holy brisket tradition. Perspective indeed. Happy holidays ~

I just finished your book and I adored it! I ate it up in a few days, much like this lovely brisket! Thank you and warm wishes from hot Miami!

Thanks Kimberly!

Only you can make me cry reading about brisket. I think there’s a connection here to the tough year you’ve had, your pique at your own “excessive” stocked freezer, and grief and loss and nourishment. These are so often connected. I wish you a sweet new year, and if you have any of that pig left in the freezer, how about a community pot luck. Invite the butcher that you miss, and anyone else. I’d happily come and cook with you!

Love you JC. xx

I made my own brisket this year, for the first time, because we didn’t “go home” for the holidays. I, of course, called my mother who walked me through the steps and I ignored some of them, but I found the brisket to be very forgiving and it came out pretty good. No leftovers for kreplach, though, so I’ll keep that in mind for next year. (I also finally learned to make kasha varnishkes correctly.) I love your story because it describes the kind of “old-world” Jewry that I never experienced but always wished I did. L’shana Tova and Gmar Chatima Tovu.

You and the flatbread story are, simply, the most! MFK (whose intitials are enough) would be so happy to know that she lives on. I find you impossible to put down, including the book and the large screen on which I read your blog. Thanks for writing. Richard

Thank you so much Richard!